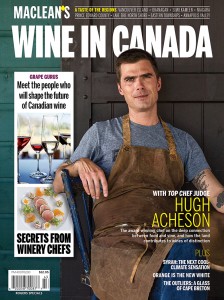

Hugh Acheson says it’s time to stop judging Canadian wine

‘The lovely thing about them now is they don’t have to prove themselves’

Share

I am a chef who lives in Athens, Ga., but the gravity of what I do every day is owed to the place I come from. Eastern Ontario and western Quebec provided a code to live by, a set of rules to cook by. I think, as Canadians, we are born with a palpable excitement about when certain things grow, like asparagus, fiddleheads, wild strawberries, tomatoes and raspberries. Even at age nine, I knew when the corn would start to come into our daily routine: a brief plunge into boiling water, the slathering of butter, the sprinkling of salt.

I started cooking as an after-school job when I was 15 years old, and that became a trade to fall back on, and then the trade became my profession, and then the profession blossomed into an endless fascination with food that I am thankful for every day. Along the way, I soaked up the ideas about the food in my community. When I was young, it was about the Portuguese bread from the corner store or the dry salami from the butcher, where we would also get Pez candies. In my teens, I remember walking through [Ottawa’s] Byward Market and reacting to the weekly changes in the produce, watching as things came in after harvest. This was product unavailable year-round, that was an expression of a farmer, a reaction to winter’s end, a celebration of the soil. After high school, I went to Montreal and worked, taking in more of the markets, the seasons and the product.

I remember the ducks the most.

They were in a bin by a sink at the restaurant. Next to the bin was a cutting board, and next to that was a grouping of vessels to hold the results of the methodical butchery that was occurring. The steps to good food were, evidently, many. One of the birds was on the cutting board in the airy kitchen, the doors open to the outside, the summer air gently blowing in from the Ottawa River. The featherless, head-on mallard was being carefully, and quickly, cut into pieces by the chef: scored, skin-on breasts for roasting, legs and neck for confit, the sot-l’y-laisse, or oysters, for a delectable treat, excess fat for rendering, and the carcass for stock. I had walked in with some palpable experience on my resumé, but nothing that would ready me for a kitchen of this stature, and asked for a job. The chef looked me up and down and asked me whether or not I could butcher one of the ducks. I said surely I could, and I dove in with zeal, and butchered it about five times slower than he did. For some reason, I still got the job.

So there I was, part of the brigade. I was 24 years old and working in Hull, Que., at the vaunted Henri Burger (RIP). The chef-owner was Robert Bourassa and the chef de cuisine was Rob MacDonald. Rob had worked in Toronto at seminal restaurants for groundbreaking chefs like Jamie Kennedy and Michael Stadtländer, but more than that, he was my teacher. I learned in a very Canadian way, surrounded by a mosaic of chefs from far-flung places, about the beauty of provenance. We had never heard the terms “farm to table” or “sustainable,” yet our food was delivered in a manner that today would make the cover of an urban-farming magazine published in Brooklyn. The back door would creak open and half a deer would be rolled in. A case of cheese would be carried in by the same hands that stirred the curds in the nearby Gatineau mountains. The beets and the onions would find their way into the kitchen through the kinship between producer and restaurant. What I learned has helped me immeasurably, giving me a clear mandate on how to source: We support our community and they support us.

I opened up my first restaurant in Georgia, in the American South, in 2000. I had followed my heart and married an American who was pursuing a graduate degree at the University of Georgia in Athens, and from there, we moved to San Francisco and then back to Athens. I was well-versed in a wonderful narrative of food, of seasons, of place that had been given to me by chefs in Canada. When I opened the back door of that first little restaurant, it was a time when the food in the U.S. was distributed, as it mostly still is, by large companies who had everything you could ever want, except a crucial component: community. I decided to invest in my area, as I had been taught to do in kitchens in Canada. Unlocking that back door to local farmers opened my mind and my heart to zipper cream peas, country hams, collards, muscadines and scuppernongs. It also showed me the importance of understanding food history in whatever community you find yourself. This endless pursuit of food and beverage knowledge continues to thrill me.

We’ve been very successful in paying homage to Southern food in modern ways while showing deep respect to the agrarian traditions that are the foundation of everything down here. We pay tribute to the land and the community and they pay us back with patronage. This way of doing business, of serving great food and great beverages without the fuss of fine dining, has become very popular in the past few years, but nothing is more difficult than doing just that. Simply great food, served by truly excited people, is a wonderfully endless task. The thanks pour in when you succeed, and the life of a chef is made whole with the positive feedback from our eaters.

Back in those days at Henri Burger, I had also learned, through osmosis, about the world of wine. Wine, for a restaurant, accounts for about 30 per cent of sales in fine dining, so I thought it would be a good thing to learn something about the subject. The sommelier, who was the maître d’ and the manager, took the time to show me some of the basics, as I watched the wines brought upstairs from the cellar below. I would see white bordeaux and ask about the relationship between tricky sémillon and the ubiquitous sauvignon blanc. I would learn about Chinon and Sancerre, St. Emilion and Pessac-Leognan, Beaune and Chambertin.

My wine education was very self-guided: a class here and there, lots of reading, a fair bit of drinking, and hours of talking to people who knew more than I did, not just about wine but about everything. The knowledge paid a lot of dividends over the years and, in retrospect, I am thankful. But there was a void: Despite having learned a ton about wine overall, I knew nothing about wines from Canada.

I know more now through thorough analysis (drinking), and have, over the last 20 years, had some really great Canuck wines from the likes of Burrowing Owl, Nk’Mip, Cave Springs, Norman Hardie, Ravine, Hinterland, Hidden Bench and Stratus, to name just a few. Gone are wines that yearned to be some global benchmark, and instead we have bottles finding true terroir in the soils at home. It’s a story of wineries getting to know their communities and themselves.

On a recent trip to Niagara, I tasted through old and young Ravines at the winery. I don’t know what I expected to find there, but the beauty of the estate and the vastness of the property were enthralling. Small-production wineries are usually rustic affairs, but Ravine was idyllic and vast, but also full of history, with everything drawing back to the land and the process of making that wine. The wines were fantastic as well, deserving of a place at the table.

There is a huge, hand-built pizza oven at Ravine and I was tasked with making some lunch. There is not a better time to cook in southern Ontario than in September. I took a beautiful Cornish game hen and broke it down, much faster than that first day at Henri Burger. I crisped off some guanciale that the winery had cured, part of an impressive charcuterie program. I sliced peaches, prepped grape clusters and roasted tomatoes and made an acidic vinaigrette to counter the richness of the bird and the guanciale. It was my food, but completely comprised of the seasonal goodness from the Niagara community. It was cooking of place.

Back in my early wine-learning days, I think my search was for a foundation in the subject. I wanted to learn about the great regions and then fill in the gaps with the fine print. Parallel to my learning, the wineries in Canada were doing the same thing, trying to mimic the fabled wines of the world, trying to make burgundy, champagne and bordeaux in Niagara and the Okanagan Valley. This is the same quest young chefs go on until they realize they should be cooking something to show where they are from, rather than aim for greatness that has already been defined halfway around the world. It’s like making Parmigiano-Reggiano in Wisconsin; it just doesn’t make sense.

What you really want to do is find, through a lot of playing around, what best shows your regional perspective. For years we were told to buy into the idea of Canadian wine for reasons that span from the patriotic to the local to the environmental. They all have credence, and I will support most of those arguments in some way, shape or form, and add one that has more power than ever before: They are really great wines.

This past American Thanksgiving, there was a wine on the table at my in-laws’ cabin in the mountains of eastern North Carolina. I had not brought it, and I don’t even know how this northern star appeared in the rural home, but it was a 2010 Cave Springs Riesling from Niagara. It sat with its label facing away, the little VQA crest hidden to my eye, until it was almost drained. At a table of eight people, it was just one bottle among three others, but it seemed to be the favourite. The meal was the Thanksgiving classic of Southern casseroles, turkey, green beans, gravy, rice, sweet potatoes and roasted fall vegetables. The riesling was singin’ harmony that just worked so well with the meal. We were all a little surprised to discover it was a Canadian wine and, to this day, no one knows how it found its way to the table.

What I am good at is ascertaining when businesses have fallen for their environment, when they have meaning, when they understand their community. That’s what I see in the wines of Canada. The lovely thing about them now is they don’t have to prove themselves. They are in a beautiful world all their own, a place I am happy to invest in. They have matured in all the right ways. They have found place.

The 2014 Wine in Canada guide digs deep into the terroir of wine and food, featuring profiles, interviews and stories on the hottest winemakers, chefs and regions that will shape the industry in the years to come. It’s now available on newsstands, online at www.rogerspublishingestore.com and on the Maclean’s app.

The 2014 Wine in Canada guide digs deep into the terroir of wine and food, featuring profiles, interviews and stories on the hottest winemakers, chefs and regions that will shape the industry in the years to come. It’s now available on newsstands, online at www.rogerspublishingestore.com and on the Maclean’s app.