Down with likeability! The problem with our ‘like’ culture

Hearts and smiley faces have become our highest cultural currency. Welcome to a world where meritocracy is replaced by friendocracy

Share

In past weeks, Hillary Clinton’s “I’m fun! I’m accessible! Vote for me!” tour saw her bonding with her comedic doppelgänger, Kate McKinnon, on Saturday Night Live, and confessing to Stephen Colbert that she and Bill binge-watched House of Cards. The charm initiative is aimed at detonating decades-old criticism that Clinton is “unlikeable”—aggressive, wooden, humourless. Past counteroffensives, which included baking cookies and dancing on Ellen, came off as phony, itself an unlikeable quality. Behind-the-scenes worry over Clinton’s perceived unlikeability is so high, Edward Klein alleges in his new book, Unlikeable: The Problem with Hillary Clinton, that Steven Spielberg was enlisted to make her cuddlier—“more Golda [Meir] than Maggie [Thatcher].” Clinton balked, Klein writes, saying, “I’m not going to pretend to be somebody I’m not”—a likeable response. She quit the coaching soon after.

That Klein, a Republican known to attack the Clintons, zeroed in on “unlikeabilty” is predictable in a country where future presidents are judged by citizens’ desire to drink a beer with them. But it reflects a larger and more odious trend: likeability’s rise as a paramount value, one that trumps intelligence, character, competence, integrity, originality, even talent.

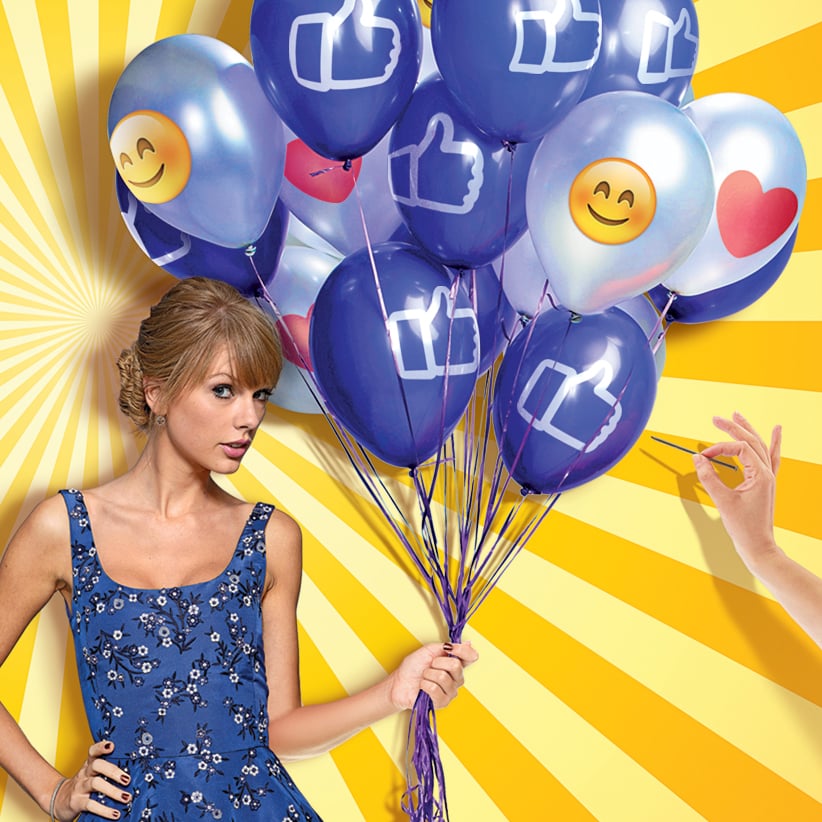

It should be no surprise that Twitter recently changed its “favourite” button from a neutral star to an emotive heart; it’s a sign of the times that a tweet about genocide can now be “hearted.” Who needs Stephen Covey’s Seven Habits of Effective People? These days we have the “13 habits of exceptionally likeable people”—a recent Forbes article—and bestsellers like Dave Kerpen’s Likeable Social Media: How to Delight Your Customers, Create an Irresistible Brand, and Be Generally Amazing on Facebook (& Other Social Networks). Facebook “likes” and Instagram “hearts” are entrenched as metrics, valued measures of success for cultural products —vital for authors, musicians, artists.

The unofficial queen of this new world order: Taylor Swift, she of 65.9 million Twitter followers and 54.5 million on Instagram. Swift is talented; she writes catchy songs. But her superstardom (and estimated $250 million net worth) clearly derives from her extreme likeability: she dances goofily at awards shows and engages non-stop with fans on social media—commenting, caring, preventing bullying, sharing pics of her cats, freshly baked cookies and slumber parties with celebrity BFFs including Lena Dunham, Karlie Kloss and Jennifer Lawrence.

To even question such affirmation and connectivity—a world in which Maya Angelou’s mantra, “People will forget what you said and what you did, but they will never forget how you made them feel,” is stamped on coffee mugs—seems churlish, even unlikeable. But there’s a lot not to like about a culture based on the most milquetoast of emotions, a creepy Brave New World-meets-high-school world where meritocracy is replaced by friendocracy, thought by feeling, and where conformity reigns. Politicians focus on relatability, not policy; and hearts, smiley faces, and other staples of the middle-school doodler are symbols of the highest cultural currency.

Likeability has always been important, of course, and tied to success. But the current focus on “like” is more mercantile than social, the culmination of a trend that began with Dale Carnegie and led to “Q scores” of the ’60s, but with a key difference. Their target audiences were CEOs, entrepreneurs and celebrities; today, social media subjects the non-famous masses to similar scrutiny. That hardly seems shocking in a world where “likes,” “views” and “followers” are economic drivers as well as self-worth measures: Facebook “likes,” we know, provide marketers with a gold mine of intimate information—from political views to shopping habits.

But the effects of a likeability fixation are more sweeping than we realize. People like, and buy, the familiar. So a world driven by “like” doesn’t stray too far from comfort zones. Confrontation and dissent and iconoclasm don’t belong—nor does the spirit of invention that can accompany them. This is not a place for Stravinskys or Philip Larkins; it’s certainly not one for Frida Kahlo, who would be trolled for her “resting bitch face.” Would Glenn Gould, a reclusive eccentric who made odd faces over his piano, prevail as a major musical talent in 2015? Unlikely. He’d have, like, zero “likes”!

The likeability obsession is particularly constraining for women. Sociologist Marianne Cooper, a Stanford professor and lead researcher for Sheryl Sandberg’s book Lean In, published an article in the Harvard Business Review in 2013, in which she cited a stream of studies that showed high-achieving women were seen as unlikeable because their behaviour violates gender stereotypes: “Women are expected to be nice, warm, friendly, and nurturing,” she said, listing the Taylor Swift playbook. Those who act assertively, competitively, or exhibit decisive leadership, are “deviating from the social script,” she writes. “We are deeply uncomfortable with powerful women . . . We often don’t really like them.”

Even fictional women are under pressure to be likeable, a point made when novelist Claire Messud sparked a firestorm after a 2013 interview in which she defended Nora Eldridge, her unlikeable protagonist in The Woman Upstairs. Nora filled a void in fiction, Messud said: “Because if it’s unseemly and possibly dangerous for a man to be angry, it’s totally unacceptable for a woman.” When the interviewer said she “wouldn’t want to be friends with Nora,” Messud rhymed off a list of unlikeable male characters, from Humbert Humbert to Hamlet, adding: “If you’re reading to find friends, you’re in deep trouble.” Novelist Meg Wolitzer dubbed the trend toward likeable characters “slumber party fiction.” Last week, the Guardian quoted Jenny Diski deriding the “mediocrity of fiction” as “really to do with feeling cosy, and that you’ve got a nice friend sitting in your lap telling you a nice story.”

Likeability is crucial for both female and male politicians, Edward Klein tells Maclean’s. It’s the reason our last prime minister spent years posing in sweaters, and why Tom Mulcair’s team tamped down his “anger” during the federal campaign, with the unfortunate result of his appearing constantly overmedicated.

Still, we’ve bought into the likeability mandate to the extent that it’s even shaping cosmetic surgery trends and how we look. In a study published in the April 2015 JAMA Facial Plastic Surgery, plastic surgeon Michael Reilly, an assistant professor at Georgetown University school of medicine, examined how women were judged pre- and post-cosmetic procedures. He found the biggest perceived improvements were in social skills, attractiveness, femininity and likeability. “Likeability is a complex subject that extends beyond a two-dimensional image of a face,” Reilly told Maclean’s. But a “likeable” face is more content, less angry and more receptive, he says: “Personality traits are drawn from an individual’s neutral expressions; it’s animal instinct to avoid those who seem ill-willed.” Perhaps, but we are also increasingly likely to interpret neutral, unsmiling expressions as ill will. Aging, for instance, reverses positive expressions like smiling. As Reilly explains it, “As people’s faces fall, the effect is essentially a frown, a tiredness.” In the past, an older face might have been read as serious or wise. Reilly perfectly articulates the modern response: “People don’t think you’re interested in what they’re saying.” And we like people who make us feel good. “We want to be affirmed and feel people agree with us,” author Dave Kerpen, CEO of New York City consultancy Likeable Media, tells Maclean’s.

The unsmiling face wasn’t always so unfashionable—historical photos and paintings are full of people with dour expressions. But it doesn’t fit the huggy mood of our times. “Resting bitch face” went viral for a reason in our time, says Reilly. “Patients, men and women, say: ‘This has been a challenge my whole life; people judge me.’ ” He prefers “resting angry face.” Either way, it’s something to fix: “If someone has a facial resting position that is a bit happier—more fullness in the cheeks, more upturn to the corners of the mouth as opposed to a resting frown—it makes a huge difference,” Reilly says.

We are now entering a phase of “like” inflation. Simply “liking” is so common (and banal) that Tinder has introduced a “super like” button. There are also signs of a brewing backlash. One of Hollywood’s best-liked (and bankable) actors, Jennifer Lawrence, recently admitted she didn’t negotiate her contract for American Hustle as fiercely as she should have, because she wanted to be liked: “I didn’t want to seem ‘difficult’ or ‘spoiled,’ ” the 25-year-old Lawrence wrote in Lena Dunham’s newsletter Lenny. Her attitude changed after the Sony hack revealed big salary discrepancies between female and male actors in the film: “I’m over trying to find the ‘adorable’ way to state my opinion and still be likeable!” she wrote. “F–k that.” The fitting ending: Lawrence’s defiance was met with universal Twitter “favourites” and Facebook “likes.”

Update