In defence of childlessness

Meghan Daum’s book explores the reasons for not having children—most decent, all human.

Share

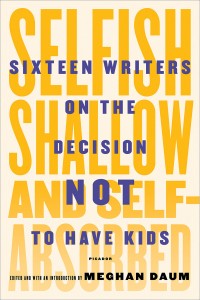

Selfish, Shallow and Self-Absorbed: Sixteen Writers On The Decision Not To Have Kids

Meghan Daum

Given the title, one might expect a quagmire of defensiveness and antagonism, kid-haters who eye roll at the mere mention of a BabyBjörn. Instead the book’s 16 essays explore a wide swath of the reasons for not having children—most of them decent, all of them human.

Some of the authors address the ramifications of physical or mental illness, broken families, and damaging childhoods on their choice to not have children. In a heartbreaking essay, Paul Lisicky, a gay man considering parenthood during the AIDS crisis, confesses, “It’s easier than you think to be indifferent to what you’re being told you can’t have.” The opposite is true for others, who firmly reject the notion that birthing a child is something they must do. Some create meaning elsewhere in their lives, as writers like Kate Christensen and Sigrid Nunez defend beautifully, while others, such as the hilarious Geoff Dyer, simply refuse to believe that life, childless or otherwise, has any meaning (and without kids, at least it’s quieter).

Laura Kipnis asks what meaning we create when, rather than sharing the activity of child-rearing, we continue to preserve a mystical naturalism between women and children, perpetuating a master-slave dialectic that keeps everyone from achieving real social and economic freedoms? This “socially organized choice masquerading as a natural one,” as she puts it, is also addressed in a way by Anna Holmes, who suggests, in her takedown of Brooklyn’s yuppie breeders, that this dominant paradigm “teaches women how to police themselves.”

For others, the question may be overpopulation, environmental worry, economic restraints, and work priorities. What’s fascinating are the ways the essays illuminate the great social transformations of our time—women’s increasing economic presence, immigration, climate change, medical ethics, normality and the family unit—and how these very public changes affect private decisions about procreation—choices not shallow, but highly sensitive. The reader starts to see how many of these “selfish” jerks were once the most marginal and powerless—women, LGBTQ, the unmarried, the ill—who, with new-found agency, decided not to have kids.