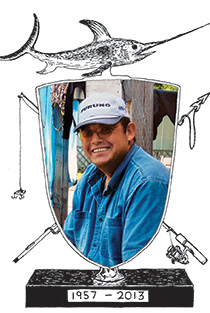

Paul Vernon Brex Malone

Loyal son, doting grandfather, and the eldest brother in a family of fishermen, he refused to let diabetes keep him from the sea

Illustration by Team Macho

Share

Paul Vernon Brex Malone was born in Yarmouth, N.S., on Dec. 27, 1957, the eldest son of Vernon Malone, a proud fisherman, and his wife, Doris. He was raised in Charlesville, Shelburne County, where the Atlantic Ocean smacks against the province’s southwestern tip. Everyone called him Brex, not Paul. “His name came off a cereal box,” his dad says. “I wanted a different name, something everybody didn’t have. There was a big box of cereal on the table—B-R-E-X—and I said: ‘That’s going to be his name.’ ”

The eldest of four brothers (Kurby came next, then Tim and Jeff), Brex grew up in a seaside home framed by his great-grandfather’s hands. The toilet was an outhouse in the yard; mom cooked meals on a wood-burning stove. His dad’s fishing boat—Pubnico Pride, a gorgeous 40-footer—was the boys’ second home. “We had been in that boat since we were old enough to walk,” Kurby says. “That was our life, and it made us a good living.” Lobster. Mackerel. Swordfish. Tuna. Whatever the season.

Brex was 15 when his father built a new house on the family land, indoor plumbing included. Sadly, what should have been a joyous summer turned tragic just weeks later: Doris, walking along the rocky shore, slipped into the ocean and drowned. “When we lost our mother, I hated, for years, anybody to mention it to me,” Tim says. “Brex was the same.” But it was Brex, the eldest, who stepped into his mother’s role, becoming a parent as much as a brother. “His whole life was about looking after us,” Tim says. “He picked up the slack.”

That September, when the school bus pulled up, Brex refused to climb on. “Dad said to him: ‘Go get ready,’ ” Kurby recalls. “He said: ‘Nope, I’m all done. I’m going fishing with you.’ ” Brex didn’t want to leave his grieving father alone. “Everybody tells me I’ve done a good job bringing the boys up,” Vernon says now. “But they brought me up.” (Vernon later remarried and had a fifth son, Ronnie.)

As men, Kurby and Tim purchased their own vessels; Brex worked for both, year after year. Famous for his giant smile, he was happiest deep at sea, unloading a trap full of flapping mackerel. During swordfish season, Brex always manned the “spar,” an observation basket high above the deck, where he scanned the surface for fins. (Other crew members, armed with harpoons, then pierced the fish and hauled them in.) “There are a lot of discouraging days in fishing, and when things were going bad, he was the most encouraging guy,” Tim says. “He would always say: ‘Don’t worry, tomorrow we’ll get ’em.’ ” Brex was so positive, so tireless, it was hard to believe he suffered from diabetes. Diagnosed in his 20s, he never left the dock—or climbed into the spar—without his medication. “He took four needles a day,” his father says. “But he never complained.”

Like his mother, Brex’s wife died young, a victim of cancer. Jody, the couple’s daughter, was barely eight years old when Elaine passed away. As always, Brex found comfort on the water. “Brex had true grit—and I’ve never picked a word lightly,” Kurby says. “It means you have courage, strength and resolve.” Nobody ever arrived at the boat earlier than Brex did; in his mind, 8 a.m. meant 7:15. “He wasn’t one to sit around,” Tim says. “If you even mentioned something that needed to get done at your house, he would have it finished and he wouldn’t even tell you he did it.”

Despite his diabetes, and the weight gain that came with trying to maintain his sugar levels, Brex never slowed down. “We’d been worried about him for 10 years now,” Tim says. “But you couldn’t have said to him: ‘Brex, don’t do that,’ because he wouldn’t have enjoyed his life.”

When he wasn’t fishing, Brex visited his father multiple times a day. He also spent as much time as he could spoiling his beloved granddaughter, Charlee—“the apple of his eye,” as Kurby says. On July 21, a Sunday, Brex stopped by his dad’s house after supper and filled his lawn mower with gas. He was due at the dock later that night for his first swordfishing trip of the summer, a five-day excursion with a cousin and a friend. “He wanted to go so bad,” Vernon says. “That was his job: up in the spar, looking for swordfish.”

On July 23, two days into the trip, Brex was climbing down from the spar to help the rest of the crew haul a catch into the boat. He lost his footing on the ladder, plunging nearly 10 metres to the platform below. Brex was 55.