How a Quebec rock-collector amassed a multi-million-dollar ‘national treasure’

Over the years, Gilles Haineault would scour a nearby quarry for interesting finds. Now, his best specimens have been acquired by the Canadian Museum of Nature at a value of $4.5 million.

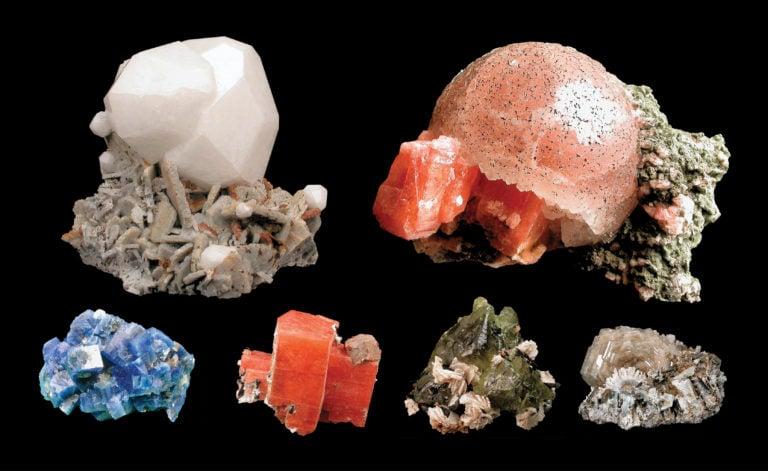

Samples from Haineault’s collection, including (clockwise from top left) analcime on microcline; an ice-cream scoop of leifite with serandite; catapleiite and natrolite; the slug-green-coloured sphalerite and albite; watermelon look-alike serandite and catapleiite; and the blue beauty fluorcarletonite (Courtesy of Gilles Haineault/Canadian Museum of Nature)

Share

It was the beginning of the 1980s when a Quebec beekeeper caught the bug—“la piqûre”—for a hobby that would fill his house with rocks. Thousands and thousands of rocks. Rocks big and small. Rocks colourful and grey. Rocks worth millions of dollars.

It wasn’t that Gilles Haineault woke up in the middle of the night and heard the call of rock-collecting, exactly. His cousin, a member of a mineralogy club in Montreal, went on excursions to quarries every weekend and invited him to join in one day. Something about the methodical search for strange, veiny rocks appealed to him. Luckily, his beloved late wife, Liliane, was into it, too, and they began regular trips to geological hot spots all over Quebec.

At a quarry only a few minutes away from his apiary in Saint-Mathieu-de-Beloeil, just south of Montreal, Haineault struck gold—so to speak.

Over the years, he was such a frequent visitor that the Carrières Mont Saint-Hilaire (formerly known as the Carrière Poudrette) gave him special access to comb through piles of blasted rock. Sometimes he would go for months without finding anything interesting—it depended where workers were blasting, and whether he showed up before they began carting rock away in heavy trucks.

“I couldn’t always be there at the right moment. It was difficult. But with the number of times I went, I had the chance to make many discoveries,” he told Maclean’s in a French-language interview, taking a break from his chief occupation of early fall: chopping firewood to heat his country home. “That I had such an impressive collection is because I kept almost everything that I found since the beginning. It’s nice to collect, but you have to preserve it.”

Over 40 years that meant preserving some 16,000 pieces of rock. His best 8,000 or so specimens collected at Mont Saint-Hilaire—ranging from fluorescent green-and-purple crystal arrangements that can fit in the palm of your hand, to geometrically intricate, rare crystallization patterns only viewable under a microscope—have just been acquired by the Canadian Museum of Nature at a value of $4.5 million.

The story of how Haineault’s collection ended up a prize acquisition for a major Canadian museum—billed as a “national treasure” comparable to the sorts of National Art Gallery works more often in the headlines—is a story about happy accidents and human curiosity.

The first serious study of the area was conducted by a Geological Survey of Canada scientist in 1912. But if it wasn’t for a commercial enterprise deciding to blast rock out of this largely nondescript hill for use in roadwork, construction and roofing shingles, the riches of the site would never have been discovered.

Its rare characteristics would not be known if not for a small group of amateur and professional collectors, either, and their willingness to regularly tread into a quarry with steel-toe boots and sledgehammers for hours of unpaid physical labour. Some, like Haineault, spent almost all their free time over decades down at the quarry in their hard hats, all for the thrill of finding tiny mineral specimens. Or for the holy grail of having a mineral species named after you, like Haineaultite—a pale yellow mineral, with prismatic crystals that have only been found as long as six millimetres.

“It’s the pride of all collectors to find a new mineral, in the hopes that one day you’ll have your name given to a new mineral,” he says. “It’s quite important: I’m going to be in the dictionary!”

***

“A basement of rocks? Oh, yeah. I’ve been in quite a few people’s basements where basically their house is half the quarry in flats and boxes and bins,” Paula Piilonen says. “There are collectors like the Horvaths in Hudson, Que. Their backyard is just one big rock pile of Saint-Hilaire.”

The pickings at the quarry haven’t been as good in recent years. Partly because of the type of rock the commercial operation is collecting. Partly because they can’t go much further into the Montérégie “mountain” of 415 m due to its other natural wonders. Much of it is conservation land owned by McGill University, recognized as a biosphere by UNESCO in 1978.

To alleviate other collectors’ disappointment, Haineault will sometimes dump some of his own Saint-Hilaire pile—the sort of specimens that wouldn’t make the cut in a museum collection—back out onto the quarry floor, says Piilonen, who is a research scientist at the nature museum and president of the Mineralogical Association of Canada. “His garbage is—to me, it’s not garbage.”

Piilonen herself has a long history with Mont Saint-Hilaire, having bought her first specimen from there at the Sudbury Gem and Mineral Show when she was in Grade 12. She visited for the first time in third-year university to hunt for specimens, and studied its minerals for a Ph.D. thesis.

There’s nothing high-tech about the collection process. “Basically you would clamber over all the rock piles and roll boulders around and sledgehammer things open. If you find something, you work around it to get as much of the rock off without breaking the crystals that are sticking out,” she explains. “Sometimes you’re lucky enough to break through into a pocket—a pocket’s basically just a big geode, a big void space that minerals break into.”

Mont Saint-Hilaire is fascinating to researchers because it is what’s known as an alkaline intrusion. The rock is created by a rare magma type that pulls in a wide array of elements, including rare earth elements, to fill the holes in its structure. As the magma cools and turns solid, diverse molecules come together in an attempt to stabilize themselves, forming unique chemical structures that repeat in a uniform pattern and form crystals.

A pocket in a pile of rock is like a needle in a haystack. Haineault, whose long-standing relationship with the quarry and obsession with its offerings meant he negotiated first dibs on certain blast areas, had a big advantage in finding them.

It came to Piilonen’s attention around 2013 that Haineault was seeking a permanent home for his collection. He wanted it to stay in Canada, preferably in Quebec. Luckily, the nature museum’s research facility is in Gatineau. After seven years of planning, negotiation and fundraising, it finally came to pass, with the help of a new philanthropic funding vehicle called the Nature Foundation, and with Haineault donating specimens worth $1 million of the collection’s $4.5-million value.

Now, the best specimens, a majority of which he collected himself—some were bought at symposiums and mineral shows over the years—are preserved along with 52,000 other specimens owned by the museum. A small number of the most beautiful crystallizations from the Haineault collection, featuring bright pink, orange, blue and green crystals, will go on display across the river in Ottawa.

It means fewer boxes in Haineault’s home and an exciting research opportunity for Piilonen. “We have this suite of minerals at Saint-Hilaire that are very strange and very diverse because the chemistry is very strange and very diverse,” says Piilonen.

In total, 430 species of minerals are present at Saint-Hilaire, making it the most mineralogically diverse place in Canada, paralleled by only a handful of sites elsewhere in the world. Of those, 66 species were new discoveries, meaning their unique chemical structures have never been found elsewhere. Some are beautiful: carletonite, named after Carleton University, is known for presenting with a vibrant royal blue hue in rectangular, almost cubic crystal formations. Haineault’s collection is expected to reveal more new species.

***

The minerals acquisition is a boon for research and a reminder of just how big a role “citizen science” and people’s curiosity about their own backyards plays in our understanding of the natural world, says Meg Beckel, the president and chief executive officer of the Canadian Museum of Nature. “Luckily, people who are curious love to share, and we love that.”

Besides, minerals aren’t just pretty to look at, whether with the naked eye or through a microscope. Their analysis has myriad applications in technology, including lasers and optics. So do rare elements extracted from mineral deposits, crucial to cellphone manufacturing. A refurbished “earth gallery” at the nature museum will explain how minerals end up in your day-to-day life, Beckel says, like on your toothbrush.

Haineault hopes researchers will be able to discover even more untapped potential. “Maybe one day we’ll discover a treatment against a virus using a mineral,” he muses. “You never know.”

This article appears in print in the November 2020 issue of Maclean’s magazine with the headline, “Rock of ages.” Subscribe to the monthly print magazine here.