How science is bringing psychedelic mushrooms out of the shadows

After a long exile from academia, researchers are now looking to psychedelics as promising solutions for addiction, depression, and PTSD

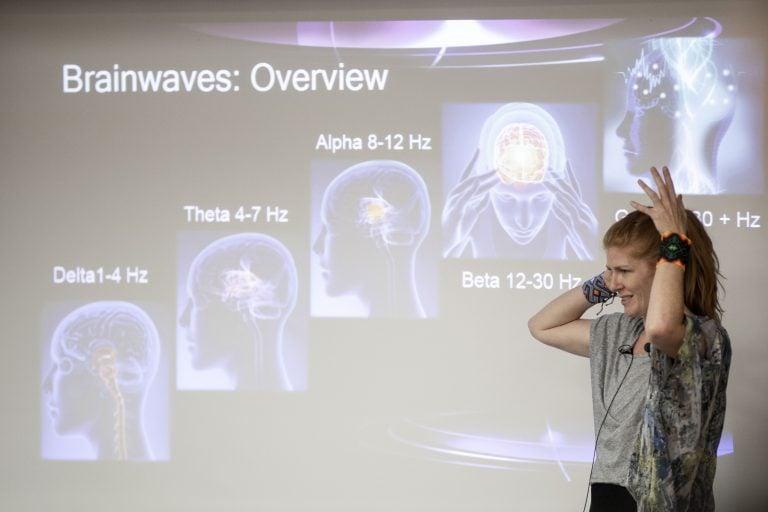

Heather Hargraves presents during the Mapping the Mind with Mushrooms event at the University of Toronto, Sept. 22, 2018. (Nick Iwanyshyn)

Share

The trick to growing mushrooms at home is patience and a good helping of vermiculite. The latter can be purchased at any store that sells gardening supplies, Antonio Cillero helpfully tells the class in a rolling Spanish accent. Most of the other instruments needed can be found around the house—jars, brown rice flour, a pressure cooker. Patience, however, comes with experience.

Fifty-odd people in an austere seminar room at the University of Toronto take notes as Cillero walks them through an abridged version of the two-week process with the attentive care of a baker. Many steps are aimed at fighting the encroachment of mould, the mushroom’s close relative and nemesis. If too much moisture is allowed to seep in, instead of a firm cake of fungus ready to sprout, the result is something much less pleasant. “I would end up with nasty muffins,” Cillero says of his aborted early attempts.

The process, known as PF Tek, can be used to grow everything from oyster to shiitake mushrooms. But considering it was pioneered by a man who called himself “Psylocybe Fanaticus,” you can assume attendees imagine other uses. Cillero’s mushroom-growing session is part of an annual conference at U of T called “Mapping the Mind with Mushrooms,” which itself is part of a resurgence of sorts.

After a long exile from academia, researchers are now looking to psychedelics like LSD, psilocybin and MDMA as promising solutions to some of the most intractable problems of modern life, including addiction, depression, PTSD and palliative care. “There is a wave of popular interest that is unprecedented in my lifetime,” says Mark Haden, a University of B.C. professor and the executive director of the Multidisciplinary Association of Psychedelic Studies.

Silver-haired and boisterous, Haden is an enthusiastic ambassador for the psychedelic renaissance. An addiction specialist, he became frustrated with the ineffectiveness of most treatment options, and for the past 15 years has been preaching the gospel of these mind-altering medicines.

The first clinical trials involving LSD were conducted in Saskatchewan in the 1950s by the psychiatric team of Humphry Osmond and Abram Hoffer, who thought the drug could be used to combat schizophrenia and alcoholism. After reading one of Osmond’s papers, author Aldous Huxley reached out, asking the researcher to provide him with a dose of mescaline, a powerful psychedelic used by Indigenous Mexicans in religious ceremonies. As a result of his experiences, Huxley wrote The Doors of Perception, a foundational text for ’60s counterculture.

By the time the Beatles put out Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band in 1967, more than 1,000 studies had been done on the potential medical uses of psychedelics. But in 1971, a UN treaty that banned most uses of psychedelics was signed, which led to laws around the world severely limiting medical and scientific research.

Finally, in the 1990s, governments allowed a handful of organizations to fund preliminary studies, and today, the science of psychedelics is starting to go mainstream. Haden believes that entire fields of study, including psychiatry, psychology and medicine, are on the cusp of being transformed. “It’s going to have a massive impact,” he predicts.

READ: Why food guru Michael Pollan decided to feed his head with psychedelic drugs

While the mechanism by which psychedelics help is still somewhat mysterious, some early results are encouraging. Samantha Podrebarac of New York University is part of a research team conducting a double-blind trial testing the efficacy of psilocybin-assisted therapy on alcoholics. Many patients, she says, report that it allows them to view their own lives and habits through an entirely new lens. The study is ongoing, but one of Podrebarac’s patients, “Peter,” who would have an average of 22 drinks on nights when he drank, described the treatment as “finding the Holy Grail and the answer to all of life’s questions,” and stopped drinking completely.

Trevor Millar, a self-described social entrepreneur, uses ibogaine, a West African psychedelic cultivated from the root-bark of the iboga plant, to help people with opiate addictions in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside.

But if psychedelics are to be widely adopted as medicine, they will have to overcome the same stigmas that led to their criminalization half a century ago. To many, LSD is still more associated with Helter Skelter than psychiatric salves. Even within the psychedelic community, those splits are apparent. “Some people think they’re useful for dancing and sex; other people think they’re useful for the treatment of PTSD,” Haden says. “They tend to talk different languages and have different focuses.”

Quantifying and understanding the effects of psychedelics isn’t easy. Researchers have developed scales to measure the degree of spiritual transformation in subjects, which has been closely correlated with achieving their goals. But discussion of spiritual experience can sound more like theology than hard-nosed science, making it a tough sell to skeptics. Podrebarac’s patients describe reliving past lives, being guided on journeys by spirits and even experiencing their own deaths. “As someone who has a scientific background, we’re seeing some very non-scientific events and observations and experiences,” she says. “It’s important to be completely transparent about all the things that are coming up, because they have a role in the healing narrative.”

Still, advocates are aware of the hazard of pushing too hard, too fast. “As we see doors opening, the ability to do these studies, to answer these very important questions, to help and heal so many people, we have to be very conscious of doing that in a good way,” says Anne Wagner, a clinical psychologist conducting a study on MDMA and PTSD. “There’s a special risk that if we don’t do it well, that door may close.”