The history and the wisdom of Hermann Rorschach’s ink blots

Rorschach’s famous ink blots have been dismissed as parlour tricks. But they’re still used worldwide, even as they turn 100 years old

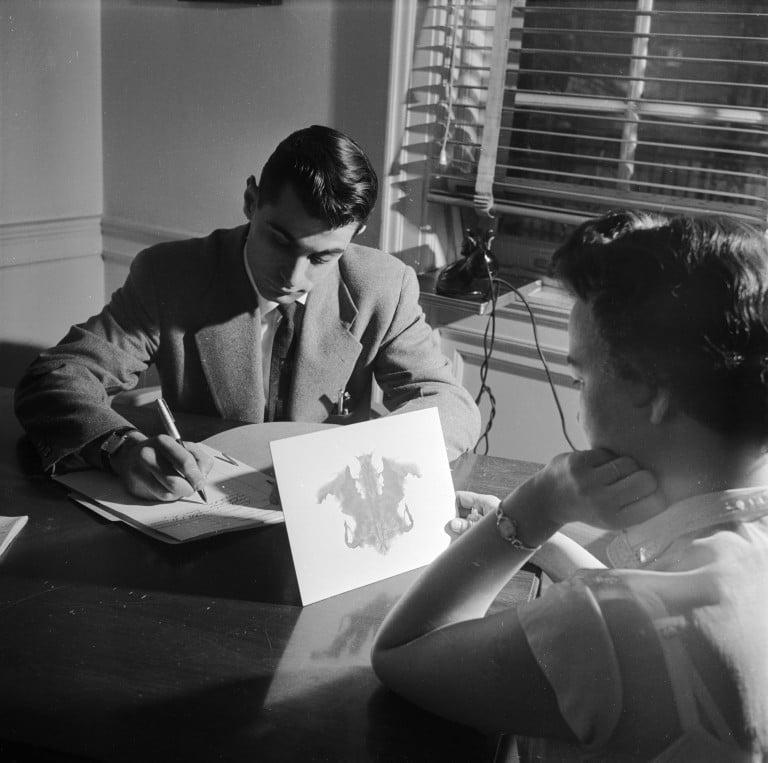

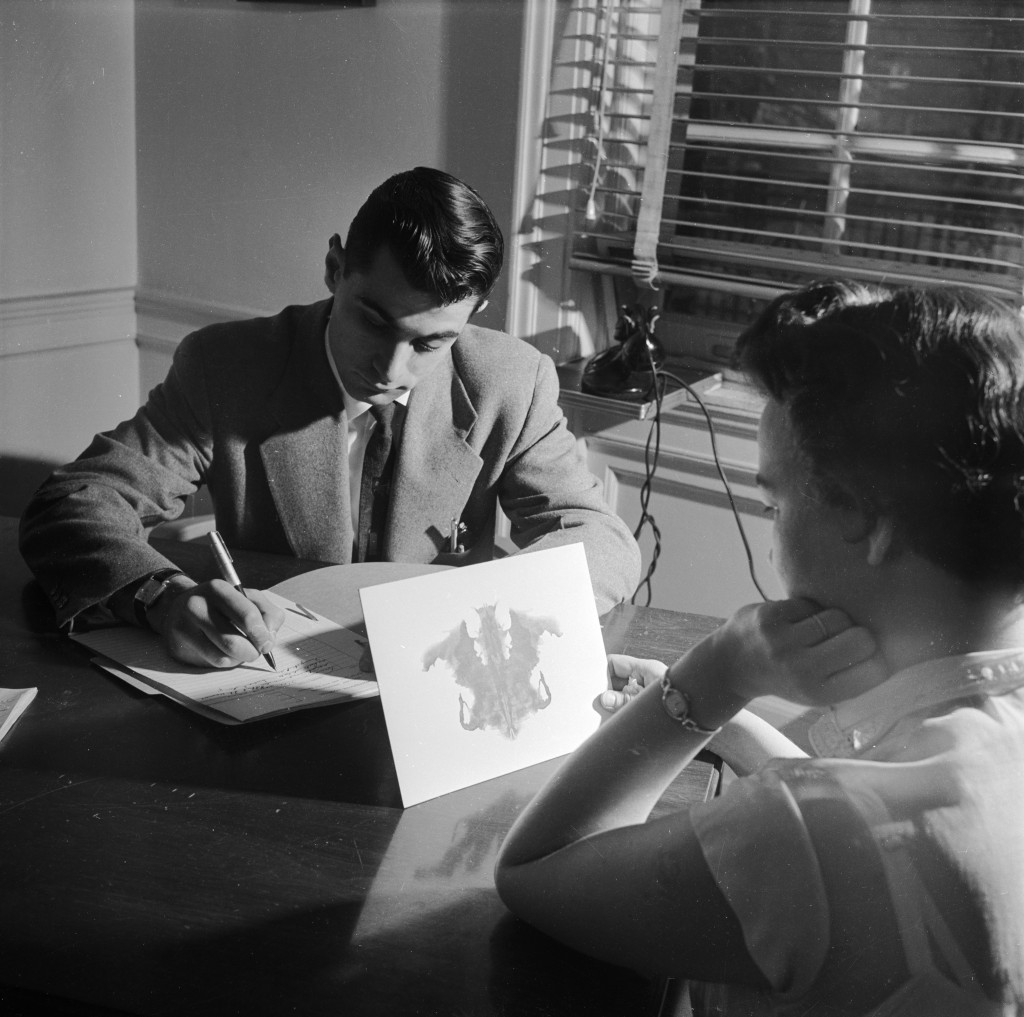

circa 1950: A doctor at the Headache Clinic in the Montefiore Hospital using the Rorschach personality test to determine whether the patient’s headaches have a psychological origin. (Photo by Orlando /Three Lions/Getty Images)

Share

In our current Neuro Age, with scientists and philosophers focused on the organic brain as opposed to the elusive mind, it’s easy to forget what a powerful revolution in psychological thinking was wrought upon the Western world a century ago. In pop culture, psychoanalysis now has little resonance outside phallic symbolism, Freudian slips—and the ink blots.

Hermann Rorschach’s iconic psychological test turns 100 this year. As detailed in Damion Searls’s new book The Inkblots: Hermann Rorschach, His Iconic Test, and The Power of Seeing, a fascinating account of the Swiss artist-scientist and the rise, fall and perseverance of his test, the Rorschach test is not in use nearly as much as it was in its heyday in the middle third of the 20th century. At that time, the ink blots—the most viewed and analyzed images of the time—were routinely shown to job applicants, accused criminals and parents embroiled in custody cases. But while it is as loathed as it’s embraced among mental-health professionals, the Rorschach test is still in use worldwide and still an instantly recognized reference.

The ink blots—unsurprisingly for images that date to the time, place and forces that created modern psychology and abstract art—simply look good, and designers rediscover them regularly. In 2011, Bergdorf Goodman’s Fifth Avenue store in New York used them in its window displays; a few years later, Saks sold Rorschach T-shirts for $98; Orphan Black and other edgy TV shows use Rorschach images, as did the video for Gnarls Barkley’s (not inappropriately named) No. 1 hit Crazy. But the Rorschach test’s enduring presence isn’t a matter of style alone.

The test is sunk deep in modern cultural DNA as a metaphor so familiar that its users have no idea they have it wrong. News media are likely to call almost any startling event or contentious person a Rorschach test. Unusual activity around Spanish bonds, according to the Wall Street Journal, formed “a financial-market Rorschach test, in which analysts see whatever is on their own minds at the time.” Both Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton have called themselves human Rorschachs, meaning Americans saw the nation they wanted or hated reflected in them.

The Rorschach became notorious as the test you cannot fail: all answers are equally valid. That also made it a meaningless test—the popular assumption is that any psychologist with a roll of paper towels and a bottle of ink can make his or her own—and a test perfectly suited for our era of “alternative facts.” A useful rhetorical concept, perhaps, but not one that bears any resemblance to the test Rorschach created.

Even Searls used to think, “like everyone else,” he says in an interview, “that the Rorschach was some old-fashioned 20th-century thing like truth serum: if you see the hopping bunny, you’re the good twin, and if you see the axe murderer, you’re the bad twin.” Searls has a fine eye for the absurd in his tale, taking care to note the thus-far unique response of a depressed Swiss farmer and early testee, who saw a “tragically misunderstood cauliflower” in one of Rorschach’s cards, not to mention that Rorschach’s nickname as a student, a tribute to his quick-sketch abilities, was “ink blot.”

Yet the American writer and translator also offers a compelling account of cultural, intellectual and social ferment. Rorschach may have toiled away alone in a remote Swiss asylum, but his native land, surrounded by the Great War in full slaughter, was at the forefront of modernity, home to Carl Jung, Vladimir Lenin, Dadaists and other inventors of the 20th century. German-language thinkers had been debating for decades what William Blake (and Aldous Huxley after him) called “the doors of perception”—how humans see, think and feel. While Freud wanted to uncover the “true” meaning of our dreams, Robert Vischer—who coined, in German, the word “empathy”—wrote of artists “feeling” their way into harmony with the world, and Wilhelm Worringer argued that some artists, facing a chaotic reality, might turn to taming it through mathematical precision in representation. In 1906, Worringer wrote Abstraction and Empathy, the title of which shows, Searls notes, “what close cousins modern psychology and modern art were.” For his part, Rorschach wanted to bring the cousins together.

[rdm-gallery id=’1221′ slug=’rorschach-tests’]

Imbued with contemporary artistic sensibilities, and convinced humans were defined as much by what we see as what—pace Freud—we say, Rorschach became intrigued by earlier ink blot tests that aimed to measure imagination. (“If patients come up with two things, then they’re not very imaginative,” explains Searls, “and if they come up with 20 things, they’re very imaginative.”) Rorschach set out to measure how his patients interpreted images. For that purpose, the test images had to be bilaterally symmetrical, because that is attractive to the human eye, and exist on what Searls calls “the boundary of something and nothing.” The final 10 ink blots, still in use today—psychologists do not make their own—are suggestive of images large numbers of responders could easily perceive. They all look like something is really there, whether a bat, bears or two waiters pouring tea. Interpretation was not the same as imagination, Rorschach stressed: unlike the latter, it imposed limits—show where you see that—particularly when two people gazed together at something in front of them.

To Rorschach’s surprise, his images soon proved predictive of mental disorders that were hard to differentiate any other way. He next started the hard work of coming up with a marking scheme. He recorded when a person gave a “whole” response (whether he or she described the entire image) or a “partial” one, whether the focus was on “form” (it’s a bat) or colour or both (it’s a black bat), and whether the testee mentioned movement of any kind (“two elephants kissing” as opposed to “two elephants”). He also kept track of the human, animal and anatomical images seen, and the percentage of “poor” form answers (“that might be a dog; maybe it’s a cloud”).

Patterns quickly emerged. Bipolar patients in a depressive phase gave no movement or colour responses and saw no human figures, but people with schizophrenic depression would frequently give movement answers. Rorschach thought, as his supporters still do, that he had crafted a valuable diagnostic tool, particularly potent in detecting latent or hidden psychosis.

That was the aspect of the Rorschach test that brought it such a resounding welcome in America, where it was adopted by the military during the Second World War and used at the Nuremberg war crimes trials and in countless job interviews. Properly applied and marked, the test works, says Searls. It does so by slipping by our defences, because “our brains are more visual than verbal. It really does tap into something more primal and emotional, so an unbalanced person is going to often fall apart on a Rorschach test, even if they don’t on other tests.” We understandably see what we see, but the mystery of the Rorschach is how often we cannot refrain from revealing our perceptions, Searls points out, citing one case where an applicant for a job with children knew that he shouldn’t be talking about all the “sexually violent stuff” he saw, but couldn’t stop himself.

The Rorschach test’s impact eventually, and inevitably, faded in the face of forces that eroded its authority: individualism, relativism, pharmacological advances and a demand for clear, quantifiable results. Perhaps the Rorschach is a metaphor after all. What society sees in it—a window into the psyche or the next thing to a parlour trick—is a direct reflection of what we expect of psychology.