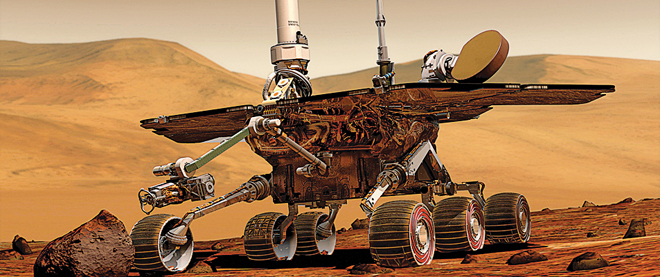

The Spirit finally gives up

When NASA scientists finally bid farewell to the Spirit rover, it was impossible not to think of it as a living thing

NASA/JPL-Caltech/Cornell/Reuters

Share

Saying goodbye is never easy, and on May 25, when NASA scientists finally bid farewell to the Spirit rover—a robot sent to explore the surface of Mars—it was impossible not to think of it as a living thing. Admitting he’d developed an emotional attachment to Spirit and its twin rover, Opportunity, Mars Exploration Rover project manager John Callas called them “the cutest darn things out in the solar system.” He and others were wistful as they praised Spirit’s achievements: intended to last just 90 days, the solar-powered rover operated for over six years, setting a record for humanity’s longest-ever mission to Mars. (Opportunity is still chugging along.)

Sent to investigate whether the freeze-dried planet was once wet and warm enough to sustain life, Spirit and Opportunity landed in January 2004, each at opposite sides: Spirit at the Gusev crater, and Opportunity on a flat plain near the Martian equator. “The environment for Spirit was always harsher than for Opportunity,” Callas said in a letter to his team. “The winters are deeper and darker,” he noted, and Gusev is a windy, dusty place, which threatened to clog Spirit’s solar panels. Scientists thought the Gusev crater might be an ancient Martian lake bed, but it turned out to be a volcanic plain—so the robot aimed for the Columbia Hills, visible only as bumps on the horizon. Not only did Spirit reach them; it actually climbed them (which it was never designed to do), and became the first robot to summit a hill on another planet.

After Spirit’s second Earth year on Mars, one of its front wheels failed. It had to improvise, driving backwards and dragging the failed wheel along the ground. “Out of lemons, Spirit made lemonade,” Callas wrote. The broken wheel eventually kicked up a trail of bright-white soil, which Spirit’s onboard tools identified as silica—suggesting that hot springs might once have bubbled up through the ground, potentially supporting some kind of microbial life. Cornell University’s Steve Squyres, Spirit and Opportunity’s principal investigator, calls this one of the most important findings of either rover.

In 2009, with dust building up on its solar panels, Spirit got bogged down in a sand trap, and as scientists used remote controls to try to dig it out, another wheel failed. Spirit sent its last transmission to Earth on March 22, 2010, as the cold, dark Martian winter approached. The NASA team radiated over 1,300 recovery commands, hoping that, when spring came, the rover might wake up again. Their last message was transmitted on May 25, just after midnight, but with no response, hope of recovering Spirit was finally abandoned.

Team members spoke about how sad they were to see the mission end, but “Spirit died an honourable death,” says Squyres, who calls this “humanity’s first real overland expedition across another planet.” That expedition continues. Opportunity is now headed for a crater named Endeavour, examining various rocks along the way. It will soon have company: next year, NASA’s Curiosity rover will arrive to search for “the chemical building blocks of life,” Squyres says, although in an entirely new location.

Thanks to Spirit, Callas told his team, Mars is no longer a strange, distant place. It’s now “our neighbourhood.”