Snowbirds who flew south for the winter became targets of a social media backlash

“Everything is open here. You can do anything—but we choose not to. We chose to stick by the rules we lived with all summer in Canada.”

Elaine and Leo in Arizona. This portrait was taken in accordance with public health recommendations, taking all necessary steps to protect participants from COVID-19. (Photograph by Caitlin O’Hara)

Share

Leo is out playing softball on a warm February afternoon near Phoenix. Infielders are required to wear masks, while outfielders stand far enough from other players that they can take theirs off. The benches are empty; everyone has to sit in their own lawn chair. And bring their own bat. “I’m not a home run hitter, but I can still run fast at my age,” says the 69-year-old from southern Ontario. “I usually play back home, too, but not this past year.”

His wife, Elaine, also 69, stays active with cycling and water aerobics, and the two go on walks without fear of slipping on ice.

Elaine and Leo were among a shrunken flock of snowbirds to fly south this winter—and “fly” is used literally in this case. With the Canada-U.S. land border closed to non-essential travel, they had to take a plane for their ninth winter down south. They had their car shipped to meet them.

READ: What can Canadians do after getting the first dose of the COVID-19 vaccines?

The Canadian Snowbird Association estimates that 70 per cent of would-be travellers stayed home this year, and those who forged on paid a price in social media backlash. It began when a few sunseekers made tone-deaf complaints about having to quarantine upon return: the critics piled on, some saying returning snowbirds would put others at risk, some simply venting their envy. (Elaine and Leo’s adult children warned them that speaking with Maclean’s would expose them to abuse; we agreed not to use their last names.) “People are so viciously negative about snowbirds, as if we’re criminals,” Elaine says. “We didn’t break any laws. We were free to leave the country and return.”

They arrived in mid-October, just as Arizona’s second wave was starting, riding out the worst of the pandemic in their over-55 community where they own a second home. They don’t eat at restaurants—not even on patios. They wear masks and invite only one couple at a time to visit. This despite relatively lax restrictions in their region: “Everything is open here. You can do anything—but we choose not to,” says Elaine. “We chose to stick by the rules we lived with all summer in Canada.”

READ: Derrick Rossi, the co-founder of Moderna, got the Pfizer vaccine and he’s happy about it

A few people in their community tested positive, including friends who were sick for weeks. But whatever fears Leo and Elaine had about contracting the virus dissipated after early February, when they drove to the Arizona Cardinals’ football stadium parking lot for their second dose of vaccine, which they received without having to step out of their car. “It felt liberating,” Leo says.

Elaine is disturbed by Ottawa’s new requirement that travellers to Canada arriving by air stay several nights in a hotel while awaiting COVID test results, describing it as “forcing people into imprisonment.” But the rule won’t affect them, because they’re driving home. They need only provide Canadian border security with a recent negative COVID test result, take another test at the border, then self-isolate at home for two weeks. Leo says they’re happy to comply.

In all, they have no regrets—save their concern, as Elaine puts it, “that some people back home paint us with a bad brush.”

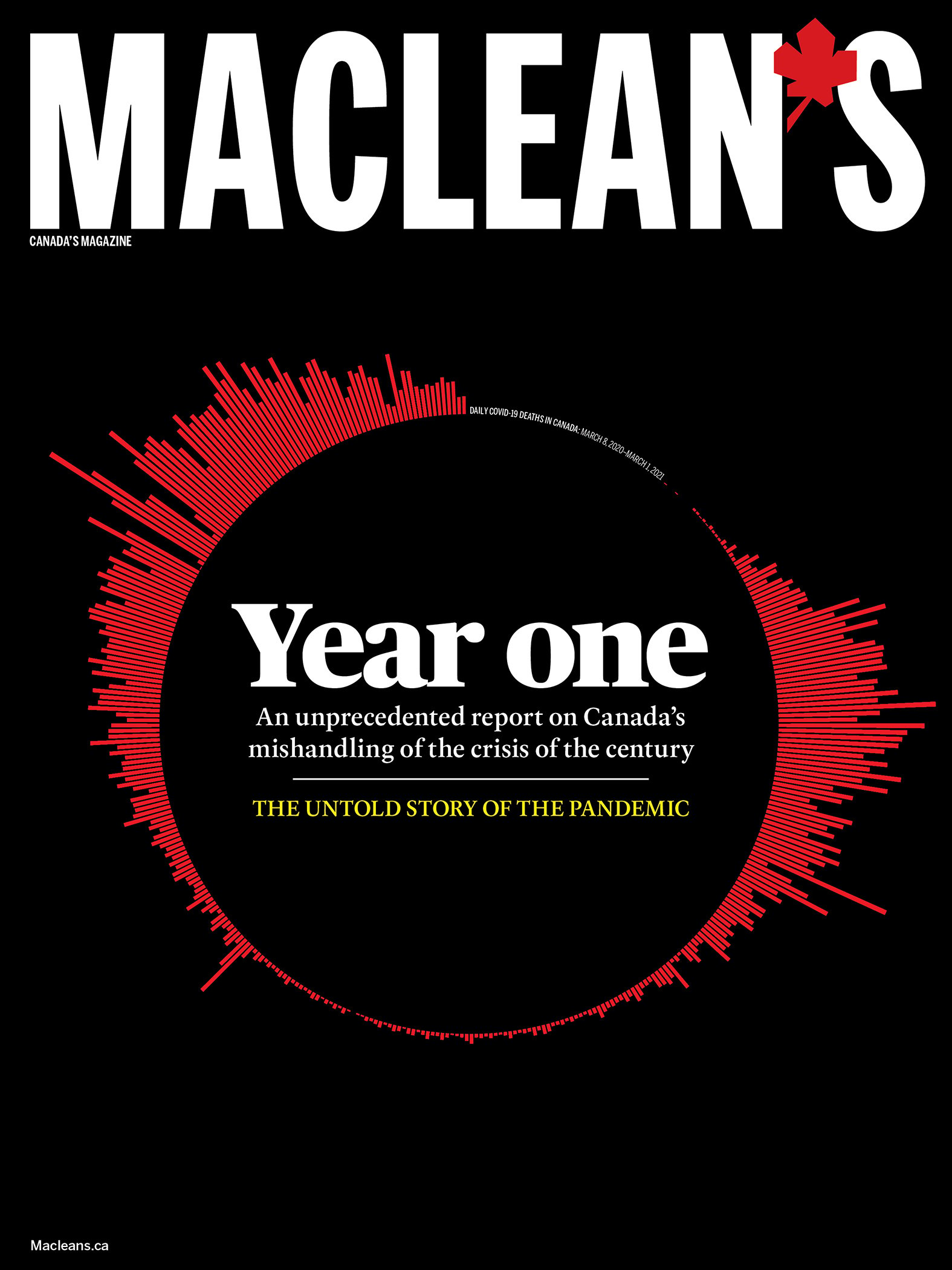

This profile appeared in the April 2021 issue of Maclean’s, where we gave our magazine over to a 22,000-word special report, “Year One: The untold story of the pandemic in Canada.” Read that whole story, and learn why we did it.