This photographer documented the cruel, perilous journey of migrants to America

Photojournalist John Moore captures the many facets of the U.S.-Mexico border—from violence to train-top rides to detention

Families attend a memorial service for two boys who were kidnapped and killed on February 14, 2017 in San Juan Sacatepequez, Guatemala. (John Moore/Getty Images)

Share

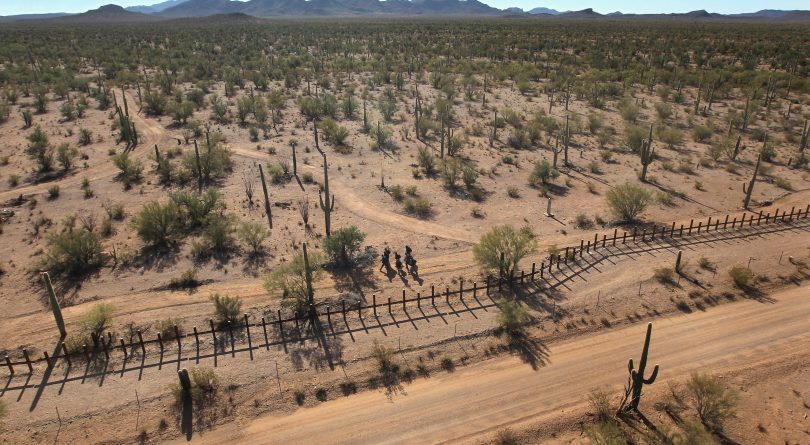

Texas-born John Moore, 51, is a veteran photojournalist who has reported from 65 countries and was part of the team that won the 2005 Pulitzer Prize for its coverage of the Iraq War. After 17 years abroad, he returned to the United States in 2008 and has spent most of the past decade focused on the constant northern migration of Central Americans and Mexicans into the U.S., as well as the American reaction. In March, Moore released his book Undocumented: Immigration and the Militarization of the United States-Mexico Border, with its powerful images that document every aspect of the migrants’ lives, but it was in June that he himself came into the headlines. That’s when a new photo—a two-year-old Honduran girl, crying after having been set down so Border Patrol agents could search her mother—went viral, becoming the image that for many captured the cruelty of the Trump administration’s policy of separating the families of migrants apprehended along the southern border.

Q: You follow this story from beginning to end—in Central America, depicting the root causes (violence and poverty), along the road and in America, with those who try to help migrants and those whose job it is to seal the border—and your access to everyone involved is astonishing. How did you manage it?

A: Some is my background. I worked in Latin America for years and I speak Spanish, which helps me with the immigrant side, and I covered the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, which taught me how to gain access to the law enforcement and military bureaucracies. But more, I think, is that people have a hunger to tell their part of the story, and my pitch is very simple: What you’re doing is important and worth showing, whether you’re a patrol agent or a migrant, and I will be as objective as possible in my captions to make the images as objective as possible. At least after taking reality into account—sometimes, as with the recent image of the child crying, the picture itself can lead to a certain level of activism. But that didn’t come from the caption, because I was very neutrally clear in it. But a picture—especially that one—can take on a life of its own after it’s published.

Q: That girl raises a question that goes to the heart of photojournalism. Is it a responsible thing to show the face of a child, or people in general, who are in such vulnerable positions? Was it an issue for you?

A: I certainly think we should be sensitive as photojournalists, especially in regards to children. In this case, I had already spoken briefly with the mother, Sandra, and I felt comfortable photographing her and her daughter. That said, it was a sad scene for me to cover. As a general rule, in public places it’s okay to photograph people, otherwise news photography would not exist. I try to be as careful as possible to not further traumatize people and still be an effective storyteller.

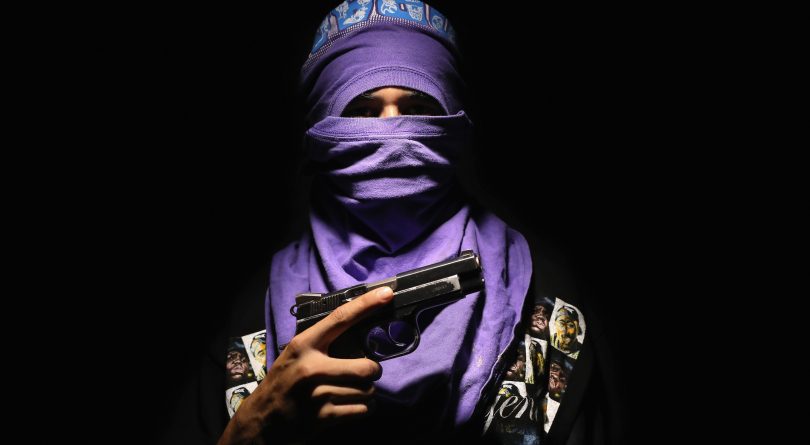

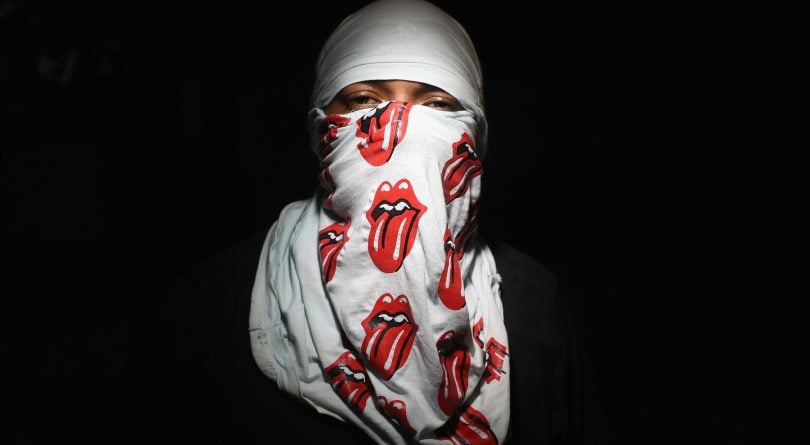

Q: Official access to the helicopters and patrols was one thing; the gang access must have been a little nerve-racking for you.

A: It was. In 2017, I made several trips to Central America to show the extreme gang violence that causes so many to leave. In San Pedro Sula, Honduras, I went out with a local crime-beat journalist. He and his crew have the trust of local law enforcement and some of the gangs. I have a lot of respect for our local journalist colleagues who cover this story on a daily basis. They are the people who have borne the brunt of the danger in horrific ways with absolutely terrible numbers of deaths.

Q: You rode La Bestia, the Beast, the freight train that so many take north. You’re not a young guy. How did you manage that?

A: I rode the Beast for a relatively short span—the people who take it to the border often ride it for weeks, with breaks. I learned the best way to board a moving freight train from an undocumented immigrant who was staying at a shelter in southern Mexico. I hired him for the day and he showed me. It was quite an experience. When I got to the top, those riding it were somewhat astonished when I told them in Spanish who I was and that I was trying to show the difficulties of their journey. They all said okay, no problem. I was there for only three hours on one of the safer sections, and I had plenty of water, but I was shaky and exhausted when I climbed down. It gave me some insight on how tough that ride is for those who travel it for weeks.

Q: You took a well-known photo in 2010, an Arizona woman in an “I Heart America” T-shirt yelling racial epithets at immigrants. In Undocumented, there is that stone-faced little boy with an “America: Love It or Leave It” shirt at a funeral for two children in Guatemala. Do those contrasts appeal to you?

A: In Guatemala I didn’t speak to the boy because it was a funeral and it would have been inappropriate, but there’s a lot of second-hand American clothing in the developing world. I’m sure he had no idea what it meant. But the irony was not lost on me—many people from his village have made their way north. As for the woman at the Tea Party rally in Arizona, that shirt was just sad to see.

Q: Is that boy in the shirt the most telling photo in the book?

A: I think so, because it doesn’t answer questions—in some ways it asks them—questions I’d like answered. For me, ambiguity in a photograph can make it more powerful because it makes people both feel and think. That’s the most you can ask for from a viewer.

This transcript has been edited for length and clarity.