What kept Canadian soldiers committed during the First World War?

Seven in ten were killed, injured or captured. And yet, they fought on.

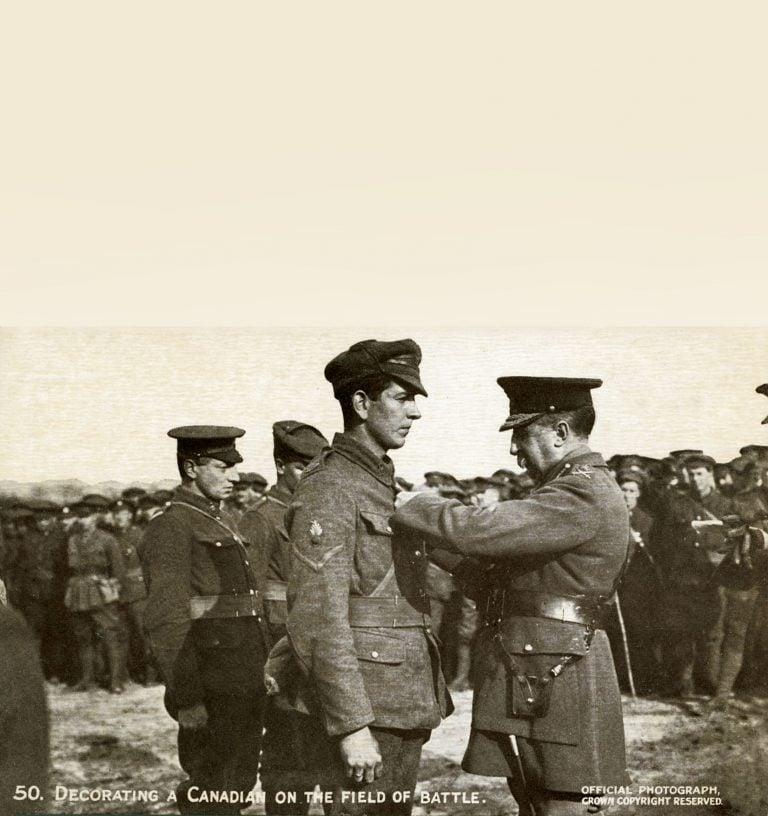

A Canadian soldier being decorated on the battle field, receiving the D.C.M. (Distinguised Conduct Medal). (Culture Club/Getty Images)

Share

Of the 345,000 Canadian soldiers who made it from Canada to France or Belgium in the Great War, more than seven in ten were killed, wounded, or captured. That number includes many soldiers who served well behind the front lines, and the casualty rate among infantry was much higher, perhaps as much as 80 percent. If there was an almost mathematical certainty of death or wounding, why did soldiers keep fighting?

First, many Canadians believed fervently in the cause. The Germans were the aggressors, and they had brutalized the French and Belgians. Some of this belief was shaped by propaganda, but much of it was fact. Kaiser Wilhelm and his Prussian generals could not be permitted to win the war.

Then there was Britain. From the beginning of the war through to the Armistice on November 11, 1918, British-born Canadians made up a very high percentage of the Canadian Corps. Such men—and most English-speaking Canadian-born soldiers—believed in King and Empire, the Union Jack, and British justice. God was on the side of the Empire, or so they believed.

Wishful thinking also kept men fighting. Others might be killed, many said, but not them. Soldiers relied on lucky charms such as a four leaf clover from home or a belief that the bible in their breast pocket would stop a bullet. Religious faith mattered to many in coping with the terror of battle. So too did the hope for a “blighty,” a wound that was not so serious as to disfigure a man, but serious enough to get him a long stay in a military hospital in Britain. The medical system was good, and if a wounded soldier made it to the Regimental Medical Officer promptly, the odds of survival were very much in his favour.

Morale was critical. The Canadian Corps had good officers and Non-Commissioned Officers, and many platoon commanders had been promoted from the ranks by 1917. Such men knew what soldiers went through, and they know how to keep their men motivated. Winning battles—as the Canadians did almost without fail from Vimy in April 1917 onwards—also created high morale, building the belief that they could always beat the Germans. But heavy casualties, such as those suffered by the Canadian Corps’ four divisions in the hard slogging of the Drocourt-Quéant Line or Canal du Nord battles, could crack the morale of even the best battalions. Soldiers who saw their closest friends killed or came to realize that even the bravest could fall might lose hope very quickly. Still, men fought for their mates, the men who relied on them and the men they relied on.

Rewards mattered, too. Some soldiers wanted a medal and would do extraordinary deeds in the effort to win one. Some hunted for souvenirs such as a German Iron Cross, spiked helmet, or a Luger. The daily shot of rum, a good meal, an occasional shower and a change of clothing—such trifles were extraordinarily important in maintaining morale.

But above all, there was military discipline, a huge factor in keeping soldiers in the fight. No soldier was a free agent. He received orders and had to carry them out– from peeling potatoes for the company cook to digging trenches and to charging an enemy machine gun emplacement. A failure to obey could bring punishments ranging from a loss of privileges to imprisonment with forced labour or even execution. Men who deserted in the face of the enemy or who failed to return from leave could face court-martial, and 216 Canadians received death sentences. Such sentences could be commuted and most were, but 25 Canadians were executed by firing squads made up of their comrades. That was a deterrent, to be sure, but many continued to desert. Extraordinarily, the vast majority did not. They carried on, followed orders, and did their duty.

J.L. Granatstein is author of Canada’s Army: Waging War and Keeping the Peace.

MORE BY J.L. GRANATSTEIN:

- He led Canada to victory in the Great War. Why did the troops dislike him?

- ‘If we hadn’t had our rum, we would have lost the war’

- The First World War brought the end of cavalry and the advent of the tank

- Conscription divided Canada. It also helped win the First World War.