Can I run for president?

Well, no, you can’t. Not if you’re Canadian (unless you’re the

Ted Cruz kind of Canadian,

then you’re fine). Here in Canada, potential prime ministers aren’t

technically subject to a set of qualifications—there are no official age

restrictions and no citizenship requirements, for example. In practice, prime

ministers are members of Parliament, which means they’re Canadian citizens who

are at least 18 years old. South of the border, however, Americans apply three

stringent criteria to their presidents: be a natural-born citizen; be 35 years

of age or older; and have been a resident of the U.S. for 14 years. That’s

just what’s in the legal books. In reality, you’re unlikely to become

president unless you’re also male, white (present White House occupant

notwithstanding), Christian, over 50 years old, have earned a

post-secondary degree, and either served in the military or practiced

law. With the exception of military service, that pretty much describes most

Canadian prime ministers, too.

American presidents: common characteristics

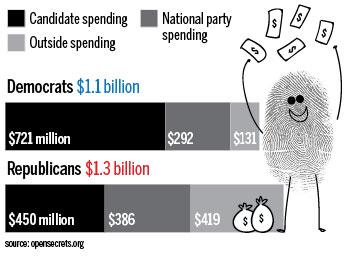

And then there’s the prohibitive cost. Once the Canadian campaign period

begins, candidates must adhere to spending limits. But in the U.S. there is no

such legislation. By the end of the (very, very, very long) campaign,

presidential candidates can spend up to

near $1 billion (all amounts in US$).

To get near the office, you’ll need friends in high places, a lot of money,

and superior fundraising skills.

Presidential election spending, 2012

The candidates

Once you decide to run, you join a pool of other interested contenders. At the

beginning of the current primary period, for instance,

23 Republican and Democratic party candidates

had declared themselves. By July, each party will have chosen just a single

nominee. These candidates will almost always fall into one of two parties —

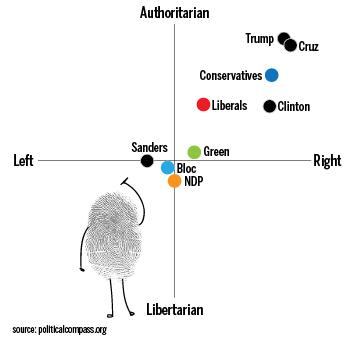

Republican (red) or Democratic (blue). American political ideology tends to

trend to the right of Canadian politics. This electoral season, the

front-runner Republicans (Trump and Cruz) don’t differ much from one another

and are ideologically far to the right. On the other hand the “left-ish” party

players (Clinton and Sanders) differ significantly — with one presenting as

even more left-leaning than current Canadian politicians.

American and Canadian political ideologies

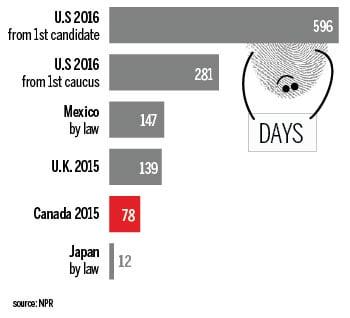

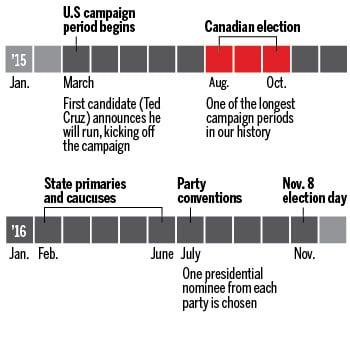

The long road begins

If there’s one good thing about the excessive length of the American campaign

period, it’s that it makes Canadians feel better about the

relative brevity

of ours. Campaigning usually starts almost two years before Election Day, when

the first candidates declare their intentions to run.

National election campaign length

Jammed into the middle of this drawn-out process is the ever-confusing season

of state primaries and caucuses. This is how 23 candidates dwindle down to

just two.

American election timeline

Primaries and caucuses

Beginning in February, a series of elections are held in every state and

overseas territory. In some states these are called primaries, in others they

are caucuses. The point of both practices is to apportion pledged delegates

among candidates in each party. Pledged delegates are party members who have

the power to vote for that candidate at their respective national party

convention, typically held in July. Basically, a primary is an election open

to registered voters in the state (sometimes all, sometimes just party

members), and a caucus is a series of small gatherings of party members who

often raise their hands or gather in groups to show their support. In order to

secure the party nomination for president, candidates need to have a majority

of delegates. This number is different for both the Democratic and Republican

parties.

Delegates needed for party nomination

The mechanisms for both primaries and caucuses differ widely by state, and

even by party. Suffice to say that almost no two contests are alike. One major

difference separates Democrats from Republicans: superdelegates. Only the

Democrats select super delegates. That group comprises 719 delegates who don’t

pledge their candidate allegiance in advance of the convention. They include

former presidents, current legislators, and elected party officials.

At the end of this five-month-long process are the party conventions. This is

where each party’s presidential nominee—typically, the one with the most

delegates—is formally nominated. Barring extraordinary circumstances, nominees

are known in advance and conventions are foregone conclusions. Keep an eye on

the Republican convention in July, which may not be so ordinary.

Campaigning and swing states

You’ll notice that once the party nominees hit the campaign trail in autumn

just before the general election, a handful of states receive a lot of

attention. These are swing states, where razor-thin polling margins mean

anyone could win. Most states are “safe,” in that voters’ preferences are

generally predictable. Candidates don’t waste resources on states where the

outcome is certain, win or lose. Strategically, it makes sense to focus

campaigns on trying to swing the undecided states.

2016 most-likely swing states

Election Day and the Electoral College

Only 538 people vote directly for the president. Wait. What? We’ll try to

explain. But trust us, it doesn’t make a whole lot of sense for a modern

democracy. These 538 people form the body of electors, known as

the Electoral College,

that ultimately vote on behalf of millions of Americans who cast ballots. On

Nov. 8, when Americans head to the polls, their choices don’t directly pick

the president, but instead they determine which candidate each state’s

electors will support. Each state is allotted a certain number of electors who

are nominated in advance. On Election Day, a vote for a presidential candidate

is actually a vote for a slate of electors who’ve pledged to vote for that

party. In many states, ballots only list the names of presidential nominees,

so it’s not surprising that so many people think they’re voting directly for

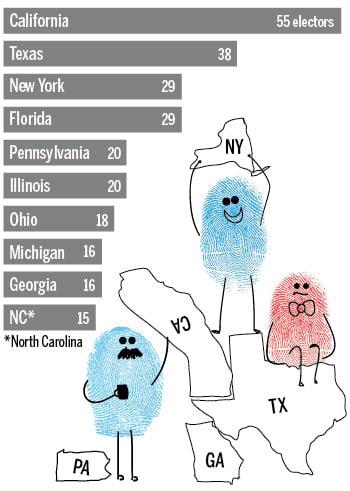

the president. Each state gets the same number of electors as it has

congressmen and senators. Each state has two senators and the number of their

congressmen is based on population. So, the more populous a state, the more

electors it gets. No state has fewer than three.

States with the most Electoral College votes

How are the electors in a state distributed between candidates? They’re not.

It’s winner-take-all (in every state but Maine and Nebraska), and the

candidate who wins the most votes gets all the electors—also known as

electoral votes. This is how entire states go blue or red. A candidate must

win at least 270 of the 538 electoral votes across the U.S. in order to

declare victory. It isn’t until December, however, that the electors head to

their state capital to cast their pre-determined votes.

Uh, could you repeat that please?

Who’s running this ship?

You know Elections Canada? Its

sole responsibility is administering Canadian federal elections—enforcing

legislation, monitoring spending, producing maps of electoral districts,

training election officers, and much more. They make sure elections run

smoothly across the country. The United States, however, has no such governing

body. In fact, there are thousands of independent local entities that manage

elections without uniform procedures. Every single state does things slightly

differently. Decisions made state-by-state (by government, local entities, or

state political parties) include whether to hold a primary or caucus, how to

select delegates, how to select electors, whether ID is required to vote, or

if you need to register in advance, what the ballots say and look like, how

votes are counted, and on and on. No wonder it’s so confusing.

Now what?

Congratulations! Now you understand American politics! … right? That’s okay,

millions of Americans struggle through this process every four years. Luckily

for the rest of us, it’s just an interesting read.

Correction: This story originally stated that the Prime Minister of Canada

is not subject to any test of qualification. Of course, constitutional

convention dictates that, in practice, prime ministers are members of

Parliament—and therefore subject to the same qualifications as every MP.

Maclean’s regrets the error.

By Amanda Shendruk, with

research assistance from

Nick Taylor-Vaisey Do you see

something that needs a fix? Email [email protected]