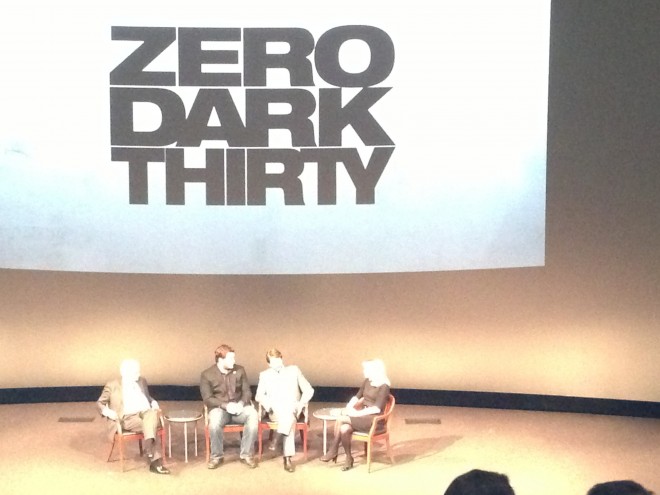

The DC premiere of Zero Dark Thirty

Kathryn Bigelow’s portrayal of torture creates controversy

This film image released by Columbia Pictures shows Mark Strong in a scene from “Zero Dark Thirty,” directed by Kathryn Bigelow. The National Board of Review has named “Zero Dark Thirty” the 2012 Best Film of the Year. (AP Photo/Sony – Columbia Pictures, Jonathan Olley)

Share

Last night, Kathryn Bigelow’s new film about the hunt for Osama Bin Laden, Zero Dark Thirty, premiered here in Washington, DC. The theatre at the Newseum was packed with journalists, talking heads and a smattering of senators. Outside, protesters in Guantanamo Bay-style orange jumpsuits expressed their opposition to torture and the way it is portrayed in the film.

A few weeks ago, the acting head of the CIA, Michael Morell, wrote that the movie gives a exaggerated impression of the role the harsh interrogation techniques played in the hunt for Bin Laden:

The movie “creates the strong impression that the enhanced interrogation techniques that were part of our former detention and interrogation program were the key to finding Bin Laden. That impression is false.”

“The truth is that multiple streams of intelligence led C.I.A. analysts to conclude that Bin Laden was hiding in Abbottabad. … Some came from detainees subjected to enhanced techniques. … But there were many other sources as well.”

Bigelow, whose previous film, The Hurt Locker, about an army bomb squad in the Iraq War, won six Oscars fincluding best picture, best director, and best original screenplay, introduced the film last night by saying she had “no agenda in making this film.” Screenwriter, Mark Boal, engaged in a post-screening Q-and-A with Martha Raddetz, the ABC News reporter who moderated the vice presidential debates. (Raddetz also interviewed Chris Pratt, the actor who plays one of the Navy SEALs who raided the compound. He described the experience of filming the climactic raid scene inside a replica of the fortress-like hideout that filmmakers had built to scale on location in the country of Jordan.)

Boal told Raddetz that he was surprised by the some of the political reaction that greeted the film before it had even opened in Washington, DC. (In addition to the CIA comments, the Senate Intelligence Committee is investigating where the filmmakers got their information.) Perhaps he should not have been surprised. It’s hard to watch this gripping and suspenseful film and not come away with the strong impression that water-boarding and torture were key factors obtaining the intelligence that led to bin Laden.

The film opens with an extensive torture scene – including waterboarding – of an apparently fictional or composite detainee, described as a nephew to 9/11 mastermind Khalid Shaikh Mohammed. Later, after his torture has ended and he has been allowed to sleep and is eating comfortably – but with the implicit threat of more abuse hanging over him – his CIA interrogators fool him into thinking that he had already began talking while under extreme sleep deprivation and had given up names that foiled a plot. They get him to relax and start talking more about his travels before his capture, including naming three other men who were with him at one point. Two of those names were familiar to the CIA already, but they third name is new; he describes the man as merely a computer guy. But this third man will turn out to be the courier who will lead the CIA to Bin Laden’s hideout. (In real life, none of the three detainees who are known to have been waterboarded gave up the courier’s name and identity.)

There is then a montage in which other detainees tell interrogators that they knew of the man, including one who says he sometimes delivered messages for Bin Laden but was just one of many couriers; it is not clear what treatment, if any, they were subjected to or even whether they were in American hands or some foreign service. Later, yet another detainee is introduced who talks freely to his interrogators because he does not want to be tortured again, he says without adding details; this detainee fills in the crucial description that the man is, in fact, Bin Laden’s most trusted courier. Yet another detainee lies about the man while being truthful about other information, which confirms that the man must be particularly important. (The rest of the hunt – learning the courier’s real name and the dogged manhunt to track him down in Pakistan — do not involve interrogations, coercive or otherwise. The CIA, for example, discovered some information about the man had been submitted by another country’s intelligence service shortly after 9/11 but had gone overlooked in its files; and used bribery, electronic surveillance, and the cell phone’s signal to hone in on their target.)

Here is a detailed New York Times report in May 2011 about the role that torture played in the trail that led the CIA to bin Laden’s trusted courier, and then to his compound in Abbottabad, Pakistan:

But a closer look at prisoner interrogations suggests that the harsh techniques played a small role at most in identifying Bin Laden’s trusted courier and exposing his hide-out. One detainee who apparently was subjected to some tough treatment provided a crucial description of the courier, according to current and former officials briefed on the interrogations. But two prisoners who underwent some of the harshest treatment — including Khalid Shaikh Mohammed, who was waterboarded 183 times — repeatedly misled their interrogators about the courier’s identity.

In his comments after the screening, Boal portrayed the movie as ambiguous about the role of torture.

“I remember hearing that the head of the CIA had made a statement about the movie and that was a pretty intense moment… I wasn’t totally expecting that,” said Boal.

“I think there is a lot in that statement that falls in line with the movie. The movie to me portrays a lot of different techniques over the years.”

Boal called “Bigelow” “gutsy” in portraying the interrogation techniques.

“The fact that she was willing to tackle that and not shy away from that part of the story, I’m very proud of the fact that she did that. I think she did a great job of capturing some of the essence of the issues involved. We are talking about a ten year man-hunt that had hundreds if not thousands of people involved…”

Likewise, former Democratic senator, Chris Dodd, now the head of the Motion Picture Association of America, gave a full-throated defense of the film: “It’s a movie. This isn’t a documentary,” he said.

The film “celebrates the work of the people of this town, to the world and to people in this country, who don’t think anything we do very well gets done at all. This is a great moment.”

Dodd compared the movie to the film Philadelphia, which raised awareness about AIDS and To Kill a Mockingbird, which highlighted racism. The torture controversy, he argued, is irrelevant.

“The fact that we are sitting here bickering a bit about whether or not there is a scene or two in this movie which some people think captures an acknowledgement or acceptance or approval of a certain strategy I think misses the point entirely. I think for years to come this film will be a way in which an awful lot of people will recognize the incredible efforts of some remarkable Americans whose names we will never ever know and never get the chance to personally thank — and for that reason I am thankful for what they did,” Dodd said.

But it was hard not to feel as if they were talking about a different, more ambiguous movie than the one that had just been screened.