In conversation: royal correspondent Robert Hardman

On the CEO Queen who remoulded an ancient institution for modern times

Share

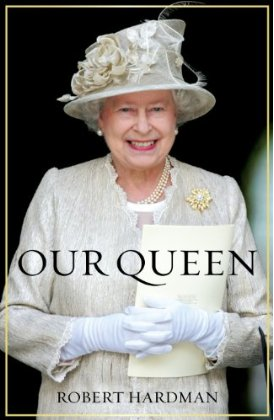

She’s been on the throne for 60 years, yet in Our Queen, royal author Robert Hardman argues that she’s changed the monarchy more than any sovereign in recent times. Although the monarchy may have once been a stuffy, ossified institution inside and out, Hardman explores its unseen young, vibrant side. The author has gone behind the green baize door for an intimate, fascinating exploration of how Queen Elizabeth II remoulded an ancient institution so that it fits into this increasingly hectic modern era. Gone are the gentleman amateurs who ran the royal household and in are professionals.

She’s been on the throne for 60 years, yet in Our Queen, royal author Robert Hardman argues that she’s changed the monarchy more than any sovereign in recent times. Although the monarchy may have once been a stuffy, ossified institution inside and out, Hardman explores its unseen young, vibrant side. The author has gone behind the green baize door for an intimate, fascinating exploration of how Queen Elizabeth II remoulded an ancient institution so that it fits into this increasingly hectic modern era. Gone are the gentleman amateurs who ran the royal household and in are professionals.

Q: You’ve been following the royal family for a long time. With so many topics available on the Windsors, why did you want to write this particular book?

A: I’ve been a royal correspondent for 10 years and subsequently I’ve written documentaries and features, so I’ve seen a lot of the monarchy as an institution. Every time I’ve had a look behind the scenes there was a sense that things were changing. Superficially it’s a traditional institution, but behind the scenes it’s not. Does she lead it from the top? Is it a hidebound old court or is it rather a quirky interesting, surprisingly modern organization?

Q: Which one is it?

A: It’s both. It still has guys in Georgian frock coats with titles like the yeoman of the glass china pantry, but you look up close and the guy’s got an ear piece. It’s ancient and modern.

Then look at the way finances have changed. The cost of the institution in 1990 was about 65 million pounds a year and now it’s about 31 million pounds a year. That’s pretty substantial.

You look at the way they interact with us, the public—the guest list at events. Twenty years ago, guests for a garden party could only bring along a spouse and any unmarried daughter aged between 16 and 25. Now you can bring your significant other, civil partner, whatever.

It’s relaxed in areas that needed relaxing but it hasn’t made the mistake of being populist. A recurring theme throughout the book is what I call the royal paradox, which is we want the royal family to be just like us but at the same time we want them to be completely different.

Q: How stuck in the mud was it back in the 1980s?

A: The court hadn’t changed much since 1888—if you were there, you were there for life. And that led to complacency. There were no cries for reform in the early days of Charles and Diana. The garden looked rosy but there were some wise old birds who realized that things had to change. For one, the monarchy was running out of money. They had to wake up and smell the coffee and set that process in motion in the mid 80s.

Q: In the book, you mention Lord Airlie, the lord chamberlain who runs the household as the key driver of change when it came to modernizing how the royal household functioned. To what extent was the Queen involved in those decisions?

A: She was consulted every step of the way. It couldn’t have happened without her. It wasn’t a case of them pulling the wool over the eyes of this impressionable, gullible lady. Lord Airlie actually went to her in the mid 80s and said, “I need to have executive responsibility. I need to do what lord chamberlains don’t normally do: I need to get in there and throw my weight around, and bring in some people who won’t necessarily go down so well.

The Queen not only agreed to that but she had to bash off some fairly retrenched forces of conservatism, notably her dear beloved mother, who could not abide any of this stuff.

From what I can gather, she’s always been open to suggestions, and much more open to suggestions and new innovation now than in the earlier days.

Q: Isn’t that surprising given her age?

A: Well, yes, exactly. It’s usually the other way around with an organization run by the same person for 60 years, you’d expect it to have stagnated to the point of ossification by now.

It’s completely different now. I got sent an invitation to some jubilee thing, and until a few years ago, to RSVP you had to write a formal letter, “Mr. Robert Hardman presents his compliments to the master of the household…” and now there’s an email reply in it, “Are you coming or not, and oh and by the way, are you a vegan?”

Q: They got lucky by starting the changes in the 80s, didn’t they?

A: That was a godsend, because when things started to go really wrong in the mid 90s, most of the reforms, in terms of the finances, management and the general attitude had been addressed.

Although it looked as though there was a sudden shocking crisis in 1992—and it was a crisis, you had a series of domestic dramas, media dramas, the fire at Windsor Castle: it was a ghastly year—when the monarchy got itself into that situation, it was far better prepared to deal with it. They had sorted out a formula for sorting out the tax situation.

Q: There is a new deal regarding the financing of the monarchy. Now it will get a share of the annual profits from the Crown Estate, the extensive Crown property that belongs to the reigning monarchy “in right of the Crown.” Now instead of all the profits going to the government’s coffers, 15 per cent will fund the monarchy. Do you think it’s a good deal?

A: I think it’s clever. Firstly as a historical precedent, in the old days before 1760, the monarchy took in all this money [from the Crown Estate] and used it to run itself. Now it’s going back to that system but instead of taking all the money, it’s taking 15 per cent. It always seemed slightly unhealthy that the monarchy had to go on bended knee to Parliament. It looked like it was begging for more cash and more handouts.

From 1990 to 2010 the Civil List, which is an annual allowance from the state to the monarch for being the monarch, that figure was fixed at 7.9 million pounds every year. They built up a surplus, so that when it came up for renewal in 2000, the government said “oh, you don’t need a pay rise, you can have that fixed rate for another 10 years.” They preserved this cash pot, made savings and for 20 years got by on the same budget.

At the end of that, instead of anyone going around and saying, “well done,” there was shouting in Parliament, “Oh my God, they want a pay rise! How absolutely disgraceful. How can they possibly justify that!” No one pointed out that in the same period that they’d been on the same allowance, from 1990 to 2010, an MP’s salary had more than trebled.

Q: When she came in 2010 for a visit to Canada, more than 100,000 people crammed onto Parliament Hill to see her on Canada Day. A normal July 1 gets around 40,000 to the Hill. The reason heard over and over was, “Well, it’s because it’s her!”

Are you seeing that now?

A: I think that’s been the big change with this jubilee. It’s very much about her. Maybe for the last 20 to 30 years it was the younger members of the family who had all the glamour around them, whether it was Diana, or Prince Charles or, more recently, the duke and duchess of Cambridge. But this is all about her. It’s as if Britain’s woken up and said, “God, you know what? She’s quite extraordinary. We’re quite lucky to have her. Let’s have a party!”