My Prediction: More ERs will close and more doctors will burn out

Without a viable national strategy, Canada’s health-care system will continue to collapse.

(Photo courtesy of CMA)

Share

Alika Lafontaine is the President of the Canadian Medical Association.

Most Canadians have only become aware of the country’s severe health-care labour shortage within the last two years. The headlines have been alarming: emergency rooms are shutting down, and patients are waiting months to see specialists. Some have even tried to recruit physicians by putting ads in local newspapers. This crisis, which has been decades in the making, is still far from resolved. It could reach a breaking point in 2023.

Physicians are extremely burnt out, and it’s no wonder why: a study from the University of Chicago found that if American primary-care physicians followed national guidelines for preventative, chronic disease and acute care, it would take them more hours than there are in a day (26.7) to see an average number of patients. You could just as easily apply those findings to Canadian doctors, who follow similar care guidelines. Our 2021 National Physician Health Survey showed that physicians are considering working fewer hours. Many of our nursing colleagues are doing the same. It’s likely that staffing shortages and access to medical care will only worsen in 2023, and patients and their families will feel the greatest burden.

Hospitals could increase physician retention rates by improving working conditions. They could train and integrate medical scribes and physician assistants to free up bandwidth for direct patient care. They could develop team-based care models where several people share the load. Some hospital-based rehabilitation programs, for instance, are forming transdisciplinary teams—of physicians, nurses, social workers and physical and occupational therapists—which create better communication and improve patient care.

Canada has also never had a country-wide human resources system dedicated to the health-care workforce. We have 13 health jurisdictions, each with its own localized plan. Many of those jurisdictions are already prioritizing mental health and increasing system capacity, but they still operate separately. Providers are burdened by red tape. I know a general surgeon who practises in Atlantic Canada and sees patients in four provinces because those are the only areas that cover particular types of care. So that doctor has to work under four provincial jurisdictions every year, losing hours to administrative work that could otherwise be dedicated to patients—or their own personal life.

Pan-Canadian licensure would remove barriers in virtual medicine. If we had pan-national licensing, doctors could provide virtual care in places where they couldn’t work before and alleviate pressure on local physicians. Imagine a scenario in which a patient in Yellowknife needs virtual care and cannot get an appointment with a provider near them because the doctors are overbooked. Under a pan-Canadian system, they could go online and consult with a licensed doctor from Calgary.

Last March, the federal government identified its top five priorities for new health-care spending: shortening service backlogs, better long-term and home-care services, more resources for mental health and substance abuse, bolstered virtual-care resources, and stabilizing primary care—the most pressing priority, in my opinion. There are reasons to hope that a revamp could come in 2023. At the Council of the Federation meeting in Victoria last July, premiers focused heavily on strengthening health-care partnerships between the provincial and federal governments, as well as on improving patient care. There is certainly an appetite for better coordination across our siloed health systems.

But talking about it is not enough. People, especially doctors, want to see action. For years, providers like myself have sacrificed key parts of our lives in service of a system that no longer works. What’s different now is that we don’t have anything left to sacrifice. There is no capacity; we’ve maxed out our time. Unless we see major structural changes, I don’t have much confidence that things will get better in the coming year. COVID revealed how close Canada’s health-care system is to collapse, but it also showed that strong collaboration can go a long way. Faced with the pandemic, leaders from across the country worked together to mitigate the virus’s damage in a short period of time. I hope we can work together again to fix the current crisis before we reach the point of no return. We’re getting close.

— As Told To Alex Cyr

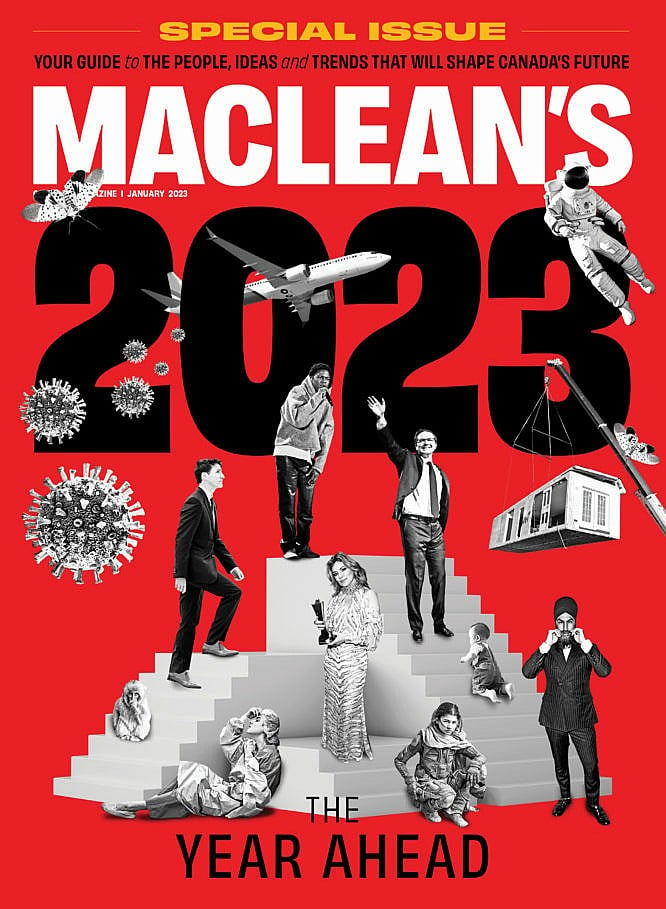

This story is part of our annual “Year Ahead” package. Read the rest of our predictions for 2023 here.

This article appears in print in the December 2022 issue of Maclean’s magazine. Buy the issue for $9.99 or better yet, subscribe to the monthly print magazine for just $39.99.