Can the National Music Centre survive in Calgary?

Jason Markusoff on how a national museum of music ended up in Calgary

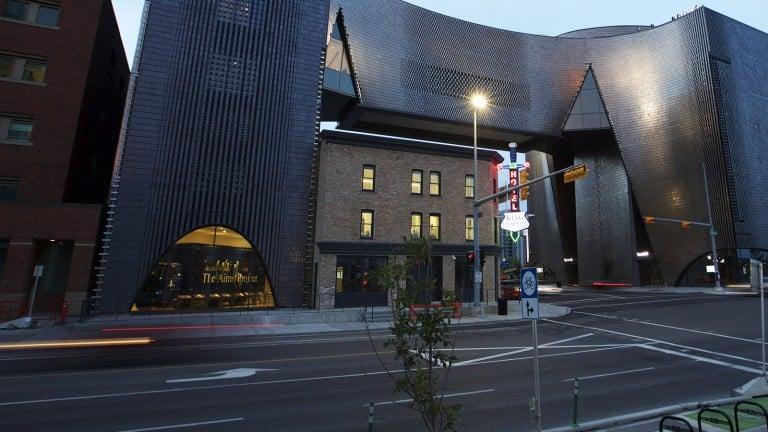

new Calgary Music Centre in Calgary, Alberta, July 26, 2016. (Photograph by Todd Korol)

Share

Canada’s Music Hall of Fame finally has a physical home, and it’s the least dazzling room in Calgary’s $191-million new palace of music. The National Music Centre is a bronze-hued and terra-cotta-tiled edifice with striking interior angles and a sky bridge five storeys over the street; its gallery spaces feature Corey Hart’s nighttime sunglasses, the stompin’ board of Tom Connors and Randy Bachman’s American Woman guitar.

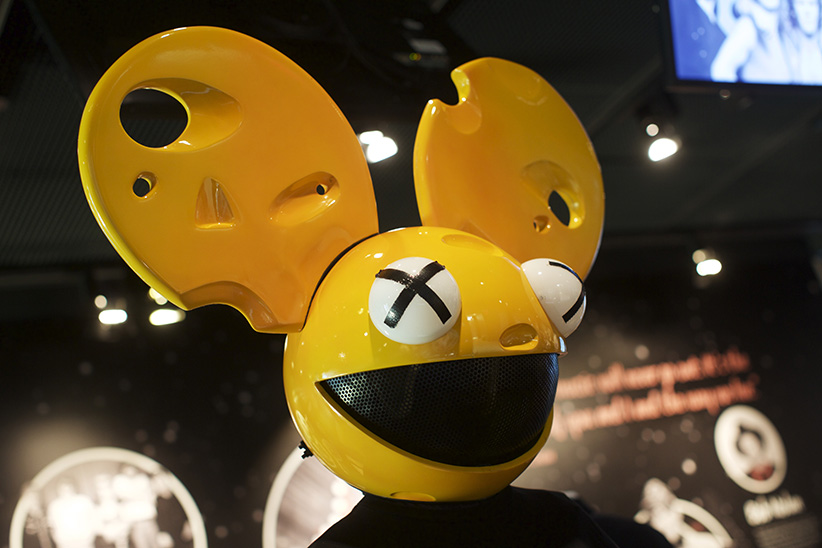

The centre’s Canadian Music Hall of Fame is a white wall with white nameplates of inductees on protruding white bricks. By the time visitors get to those fabled names on the centre’s top floor, the iPod shuffle of stories—of Glenn Gould and Maestro Fresh-Wes and Gilles Vigneault and Rush and Deadmau5—have already been told.

The NMC complex, named Studio Bell, is a sort of year-round embodiment of the Juno Awards. It opened in July ahead of Canada’s 150th, a birthday that will get citizens thinking about our musical landscape. It’s always been a complex story to weave together coherently. “What defines all these artists? They’re Canadian—I always say the weather,” says Larry LeBlanc, a veteran music journalist.

But a Calgary group succeeded in creating a CanCon playground-museum to the masses, after repeated attempts floundered elsewhere, mostly in Toronto. CARAS, the agency that runs the Junos and the Canadian Music Hall of Fame, never wanted it outside Toronto, says Jasper Kujavsky, who worked on museum efforts in Hamilton and Toronto. Government funders wouldn’t cough up, not with more traditional asks coming from galleries and science centres, he says. “This was perhaps seen as more of a—I don’t want to say a luxury, but something not on the front burner as a priority.”

By the time CARAS launched talks in 2011 about a Calgary-based hall, the NMC was already charging forward. It had a majestic design by Portland’s Brad Cloepfil and $75 million from the federal, Alberta and Calgary governments. If the Hall of Fame room seems like a sort of afterthought in the centre, that’s because it sort of was.

The centre’s unlikely success to date pairs with its unlikely roots. It all started in 1986: a symphony hall’s giant concert organ was a gift by the foundation of billionaire Ron Mannix, part of a construction and energy dynasty. Mannix then helped build around it, with an international organ competition and a small keyboard museum. That laid the groundwork for a music foundation with a growing collection of toys like Elton John’s old piano and a legendary Rolling Stones mobile studio. As ambitions boomed apace with Alberta’s economy early last decade, CEO Andrew Mosker pitched creating a Canadian music museum and non-profit artist incubator. The board signed on for the NMC, including Mannix: his company and subsidiaries donated more than $10 million and sold the centre a downtown office building for $1 so its office rents would be a revenue stream. (The Mannix family is famously publicity-shy; Mannix could not be reached for comment through his company.)

Securing money proved easier early on than winning over a Toronto-centric music industry. Mosker spent years getting to know record executives, and tapped LeBlanc to help open doors to artists like Joni Mitchell and Neil Young, hoping for mementoes. A sneak preview during this spring’s Junos in Calgary won over remaining doubters, Mosker says. “We’ve succeeded in building a bridge to the east. Now it’s up to us to sustain it and program the hell out of it,” he says.

The idea of the NMC launched in a boom, but fewer Albertans can afford admission fees in the bust. Two other national institutions sit outside Ottawa—Winnipeg’s human rights museum and Halifax’s immigration museum at Pier 21. Both are federal entities under the Museums Act, but Mosker doesn’t want the NMC to become a “rigid bureaucracy.” His complex will try, for now, to survive without operating subsidies. Organizers still need to raise more than $50 million to pay off the building cost. But by striking those opening chords, they have gotten much farther through the song than Toronto players ever could.