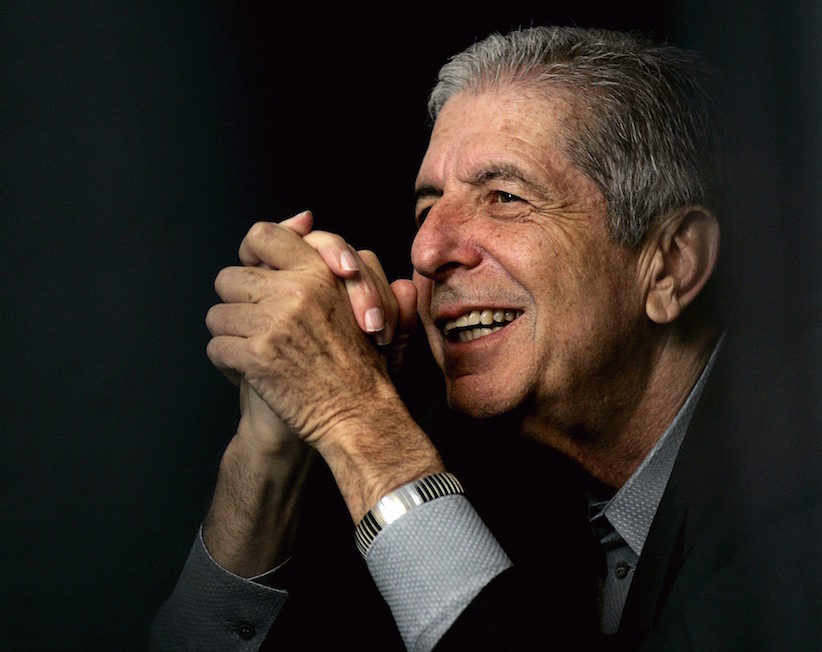

‘Leonard, we appreciate the gift.’ In appreciation of Leonard Cohen

Brian D. Johnson’s never-before-published ode to ‘our scout on the front lines of love, guiding us into the beauty of the moment, but with a cautionary word’

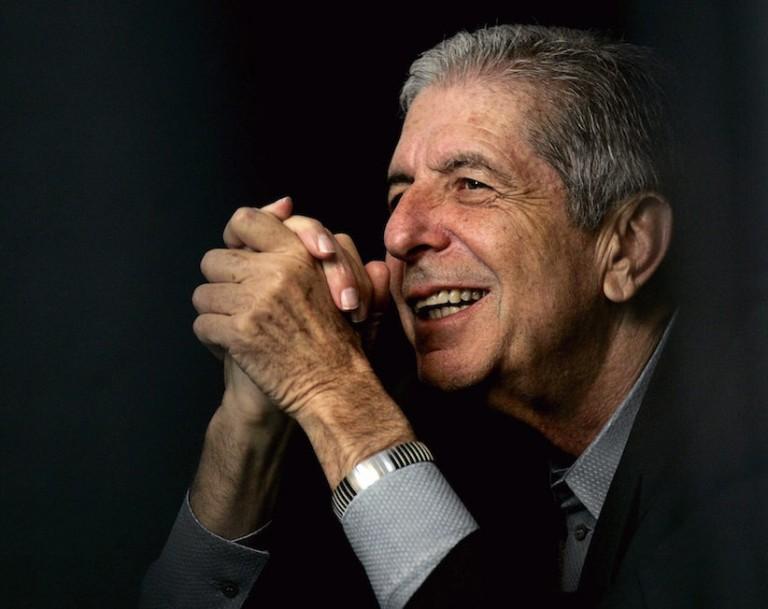

Leonard Cohen Listens to partner Anjani Thomas sing to thousands of people, while taking a seat at the back of the stage during a free concert on Saturday, May. 13, 2006 in Toronto, Ont.

(CP PHOTO/Nathan Denette)

Share

(CP PHOTO/Nathan Denette)

In 2008, Brian D. Johnson—Maclean’s film critic who has interviewed Leonard Cohen and followed him closely—was asked to write an appreciation of Cohen’s work for a concert brochure. It never got around to being used. But in the wake of the great Canadian poet and artist’s passing at the age of 82, Johnson found the essay in his archives—and as you’ll read, it has stood up beautifully as a grateful appreciation for a career and life that found joy in both pleasure and ugliness, in both the minor fall and the major lift. If you’d like to share your story of Cohen, and how he touched your life, we’d love to hear it.

When I was invited to write an appreciation of Leonard Cohen, it occurred to me that it would amount to repaying him in kind. Leonard has made a lifelong mission of perfecting the art of appreciation. Through the intimate engagement of his words and music, he arrests the moment and magnifies it. We are his guests, and one by one, he offers to intoxicate us. He manages to convey that he appreciates us—the audience, the reader—as fully as we appreciate him. A gracious host, he meets us more than halfway. On the crowded corner of Boogie Street, he pulls us into a quiet enclave. Even in a packed auditorium, as the crowd dies down, a song or poem unfolds as a private act of love, a mutual prayer. The music makes it physical. And it all comes down to the voice.

It’s a voice that always speaks to us in the strictest confidence, ushering us into a mirrored chamber with words as plain and tangible as wine or bread. It envelops us in a comfort and warmth, but takes us off the edge of the map to a region that feels both familiar and foreign. To a place near the river where the sun pours down like honey. A thousand kisses deep to the end of love. A place that looks like freedom but feels like death. And a broken hill where a singer begs to share his solitary confinement in the Tower of Song.

MORE: Read Brian D. Johnson’s last profile of Cohen, on his last album and mortality

In trying to convey what there is to love about Leonard, it’s hard not to just quote the man’s words and leave it at that. His songs, with their Aegean echoes of ancient pleasures and Biblical fire, are not just odes or stories or chiming rhymes of wisdom. They are places. You can picture them, physically. And you can enter them. Each song is like a room of its own, bare and sparsely furnished, with a wooden table and a narrow bed, yet voluptuous with a lucid, early-morning light.

Over the years, many fine singers, from Jennifer Warnes to k.d. lang, have guided us into these rooms and embellished them exquisitely. But no one occupies them quite like Leonard. It’s often hard for an artist to appreciate his own work, to read or hear its beauty as if it actually belonged to someone else. That requires years of distance, and most performers can’t afford to spend enough time separated from their own material. But Leonard has taken long retreats from both his repertoire, and his audience, whether at the monastery on Mt. Baldy or “blackening pages,” as he likes to say, in the privacy of his home: living a writer’s life.

Over the years, as a journalist, I’ve been lucky enough to spend some relaxed moments with Leonard, a precious sum of interviews and dinners and drinks. By the time we became friendly, he was off the road, and down from the mountain, making lentil soup in his kitchen and fixing the toaster. The Leonard I got to know seemed freshly comfortable in his own skin, having watched a lifelong depression evaporate, as if by magic, in the mid-’90s. He revelled in the creative life, happy to compose music in his home studio in Los Angeles, or to sketch the gazebo in the park outside his window in Montreal, to write and produce an album for partner/protégé Anjani Thomas, and to hand-craft his latest anthology of poems, The Book of Longing. He wasn’t keen on going out much. But he kept busy. Then various circumstances conspired to bring Leonard back into public life. And now he’s going out all the time. Or, as he told me one night after a concert, “I’m being sent like a postcard from place to place, and it’s wonderful.”

Early in this new tour, I asked Leonard about how it felt to perform again after such a protracted absence. It had, after all, been 14 years since he was last on the road. “One of the surprises,” he said, “was getting to know these songs again. I hadn’t really looked at them for a long, long time. The songs are good. They hold up. You can enter them. There really is a place to live in them, and a place to move in them.”

Leonard’s music has been with us for a good long while, and its architecture is built to last. Some of us are old enough to have discovered him in the 1960s, at an age when we were also discovering love and poetry as if they’d just been invented, along with music and politics, sex and smoke, all those overlapping realms of infinite possibility. Leonard was a poet, a novelist and a folksinger. Poets turning into folksingers was something new at the time. And he assumed the stance with such open-hearted candour and grace—as a vocation, not a career—that many of us came to believe, naively, that we too could be poets and folksingers. (The first and last song I ever learned to play on guitar was “Suzanne.” I never got beyond it.)

MORE: In 1966, we asked, ‘Is the world ready for Leonard Cohen?’

Leonard was part of an enduring Canadian trinity that included Joni Mitchell and Neil Young. He was the campfire’s tribal elder, and not just because he had a few years on Neil and Joni. As a young man throwing open the windows of English Montreal’s literary salons, he bridged the distance between the lions of Canadian letters, poets like Irving Layton and Frank Scott, and a new world where poets had names like Dylan and Donovan. He was in some ways akin to Pierre Trudeau, Canada’s pop star prime minister, a fellow Montrealer who became his friend. Trudeau and Cohen were both embraced as modern icons of bohemia, and paragons of cool, but with a European elegance and savoir faire. Leonard never lost sight of the Old World—or the Old Testament.

As his star rose, there were larger phenomena churning up the pop landscape, from the Beatles and the Stones on down. But Leonard stood boldly apart, immune to fashion. He never “went electric.” He wasn’t trying to set the world on fire. (A burning violin would suffice.) And while others competed to reinvent the pop prototype, he kept going back to the old musical scriptures, to the gypsy swirl and the runaway waltz, to the saloon-car sway of pedal steel and those empty rooms of song where Hank Williams would feel at home.

But for someone so intimate with the past, Leonard has always been a step or two ahead of his time. As my generation chased romance in the Mediterranean and lit fires on the beach, he had already been there long before. He was our scout on the front lines of love, guiding us into the beauty of the moment, but with a cautionary word that its embrace is out of our hands, and that there’s no escaping love’s undertow of emptiness and loss.

Leonard taught us to take pleasure in perfection, and its inevitable ruin. In an interview for the Canadian arts magazine Border Crossings, when Robert Enright asked him if the quest for beauty “is central to what you do,” he had to assent—yet you could sense a nagging resistance, as if “beauty” does not begin to describe what he’s after. I encountered the same thing when Leonard kindly agreed to contribute to a score for a short film I’d made about dancing hands. After viewing a rough cut, and trying to figure out what irked him about it, he delivered a useful but devastating critique in a single line of email: “Too much beauty.” By which I think he meant to say that the beauty was unearned. In Leonard’s work, the beauty always pays its freight.

Since the revelation of “Suzanne” and its youthful invocation of a state of grace—those pronoun variations on “he touched her perfect body with his mind”—beauty in Leonard’s work, as in the world itself, has become more complicated. In the public mind, he may have been stereotyped as the prince of gloom. But for every dark lament that brings a tear, there’s a blacker joke that brings a smile.

The modern world is littered with singer-songwriters, not to mention “all those lousy little poets,” but no one has examined the crimes of love and the supplications of sex with such forensic acuity as Leonard Cohen. By 1977, while still in his early 40s, he was already conducting autopsies of eros in Death of a Ladies’ Man. A decade later, with his album I’m Your Man, he converted his role as Everywoman’s suitor into a pose of burlesque submission— “If you want a lover / I’ll do anything you ask me to / And if you want another kind of love / I’ll wear a mask for you.” At the same time, he cast a sweeping light on a pre-apocalyptic landscape of corruption and decay—”Everybody knows that the Plague is coming / Everybody know that it’s moving fast.” The visionary prognosis of Leonard’s songwriting came to a head with The Future, a masterpiece and cultural milestone that Robert Enright astutely compared to T.S. Eliot’s The Wasteland. Nine years before 9/11, this under-heralded album presaged a climate of global catastrophe that we’ve come to accept as second nature. By the time all hell was breaking loose in the skies of Manhattan, Leonard had already retreated to the less turbulent, more reconciled meditations of Ten New Songs, later followed followed by the quiet watercolour strokes of Dear Heather.

MORE: Brian D. Johnson’s 2001 profile of Cohen, with interviews around 9/11

What’s extraordinary is that, over the course of some 40 years, Leonard has never let his work succumb to commercial cliché or complacency. On the contrary, he keeps shedding past lives and closing in on the most elemental issues with a rigorous lack of compromise. In so doing, he has created an epic repertoire that offers the true measure of a man, in the Shakespearean sense. From the young poet with the Aeolian wind in his sails to the ancient mariner exploring the cold fathoms of shipwrecked love, Leonard has taken us full circle. Through his life and ours.

It’s encouraging to see that both the singer and the songs have gained wisdom with age. Brave ambitions of perfection and beauty are gently revised—Forget your perfect offering / There’s a crack in everything / That’s how the light gets in. But the voice, golden in its imperfection, warms and deepens with cellaring, like vintage port. And after such a long absence from the field, as Leonard shares it with an audience for what could be the last time, it feels like the voice belongs to us somehow.