Why Archie comics always mattered

Even before today’s reboot, Archie comics could be great. Here are some of its greatest arcs according to Jaime Weinman

Share

Today’s the day! Today’s the day Archie launches its new #1 issue, revamping the world’s longest-running, anachronistic humour comic in a slightly more modern way. Mark Waid (The Flash, Daredevil) is the writer and the first three issues will be drawn by Canadian artist Fiona Staples (Saga). Staples’s art is the highlight of the first issue; with colourists Andre Szymanowicz and Jen Vaughn, she’s doing a beautiful job creating an art style that’s less “cartoony” but still appropriate for a light comedy. Writer and artist do a particularly good job on Jughead, a character who’s easy to get wrong; he’s completely right here, in attitude, look (he has his beanie, of course; it’s been out of date since the ’40s, but you can’t have Jughead without it) and body language. Other devices, like Archie talking to the reader a la Zach Morris or Ferris Bueller, will take some getting used to, and it’s too early to tell if future issues will be as funny as the very best Archie work. But it’s a promising start that honours the spirit of the traditional Archie story while expanding it to a serialized, 22-page format.

But since today is the day when a new era begins for Archie, I thought I would talk a bit about the past of Archie, and specifically, recommend some great Archie comics. I’m an Archie fan, which is not to say that I’m a fan of the way the company treated its great artists, or that I deny they put out a lot of mediocre comics. But the company’s output still seems underrated to me, in part because they’re in a style — the monthly humour comic with little or no continuity — that has never been fully appreciated in North America.

With this type of comic, you can’t recommend memorable story arcs—there weren’t any, unless you count the time Betty and Me turned into a parody of the soap opera parody Mary Hartman, Mary Hartman). The usual format for an Archie comic was that it consisted of four stories, two of them six pages and two of them five pages, plus the occasional one or half-page gag. Each story was self-contained, with no continuity, so if Jughead ended the story by turning into an ostrich, you didn’t expect him to still be an ostrich when you turned the page. Also, the comics deliberately have very little to do with the way teenagers act and talk, because they weren’t aimed at teenagers; they were for little kids who thought that was what life would be like when they became teenagers. The best Archie writers, like Frank Doyle, made no attempt to mimic the way real teenagers acted and spoke, instead using stylized, deliberately old-fashioned slang. One difference with the new Waid run is that he’s actually trying to get teenagers to read the comic, which requires a slightly more realistic approach. But expecting that from a traditional Archie comic is beside the point.

Nonetheless, there’s a lot of excellent work in the Archie vaults. It helps that because Archie outlasted most of its humour competition, it had some world-class artists. Dan DeCarlo, its most prolific penciller, became available to Archie full-time in the 1950s after Stan Lee had to lay off most of his staff. DeCarlo was a great humour and pretty-girl cartoonist, respected by everyone in the business (artists from Bruce Timm to the Hernandez Bros. are openly and hugely influenced by his work). Archie didn’t pay great, but by all accounts they always paid on time, almost as important to a freelancer as getting paid well. And so they got a world-class artist at a bargain price. This is no longer an option, because good artists have more options, thankfully: Staples is a world-class artist, but is only doing three Archie issues before getting back to work on the hit comic she co-owns, Saga. Part of the appeal of an old Archie comic is seeing some of the best non-superhero artists in the business give their all to these frivolous, farcical stories.

Unfortunately, there’s been very little effort to collect Archie comics in a systematic way. There are some hardcover volumes from Dark Horse collecting the earliest Archie comics, and IDW put out some collections of restored stories by the great Archie artists, including four DeCarlo volumes, but the stories are kind of randomly selected and arranged. For the most part, the great Archie runs require hunting down back issues or waiting for someone to create omnibus collections. But here’s what to look for.

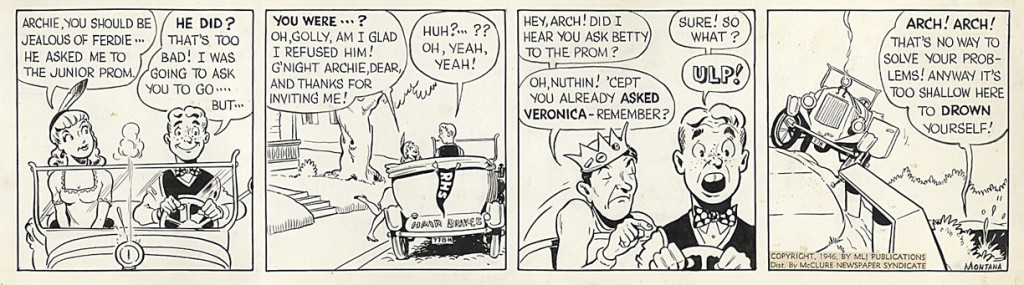

Archie newspaper strip, 1946-1948, by Bob Montana

Fortunately, this one actually has been collected in a restored book. Montana was the creator of Archie, though ever since he died the company has insisted that he merely “created the likenesses” of the characters (the publisher, John Goldwater, insisted he came up with the idea, and the company has officially credited him as “creator” ever since). After teh Second World War, he was mostly taken off the comic books and put on the more prestigious job of writing and drawing the daily newspaper strip. Later the strip would become a good but not great gag-a-day strip, so later collections of these strips aren’t as essential. But the first three years of the dailies are beautifully drawn and very funny, with hints of the slight edginess and dark humour that comics lost in the 1950s.

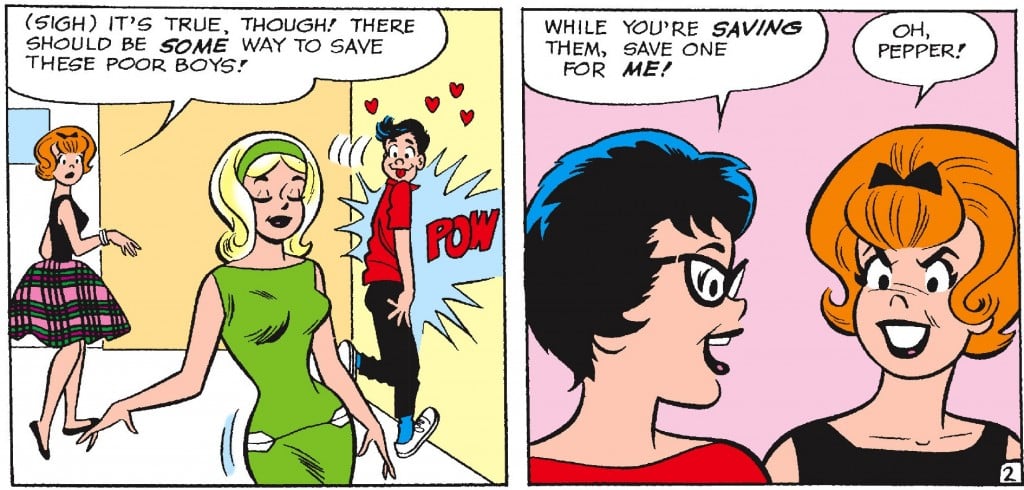

She’s Josie 1-16 by Frank Doyle and Dan DeCarlo

Before the Pussycats, “Josie” was a comic strip DeCarlo pitched starring a redheaded teenager named after his wife, her ditzy blond friend Melody, and her brainy, bespectacled friend Pepper. When it wasn’t picked up for the newspapers, he sold it to Archie comics (the question of whether he sold it outright, or still retained the rights to his creation, was the basis of the lawsuit that eventually got him fired from the company). The writing was by Frank Doyle, Archie’s most prolific writer, whose storytelling and dialogue technique were miles ahead of most comics writers, in any genre. And DeCarlo, working with characters he created himself, outdid himself at all the things he did best: great clothes, beautiful girls, slapstick and charm. Kurt Busiek loved this run so much that when he wrote Iron Man, he named Pepper Potts’s dog “Sock” after Pepper’s boyfriend in She’s Josie; “Josie was sheer delight, a perfect meringue of a comic,” he says. “I’ve been demanding a full chronological archive of Josie reprints for years now, but I’m not sure the people at Archie are listening to my incontrovertible arguments and my dog doesn’t listen to me all that often.”

The best issues are the earliest, under the title She’s Josie (issues 1-16); running from 1963 to 1965, they embody the look and spirit of the early 1960s — the other ’60s, the JFK/LBJ era — better than any comic book ever published. One thing Archie comics have over superhero comics is that although they don’t represent the way teenagers acted, they were alive to fashion and contemporary trends in a way that most comics simply aren’t. When you read She’s Josie, you’re not seeing 1964 as it was, but you’re seeing it as its young readers thought it was, and that’s almost as important.

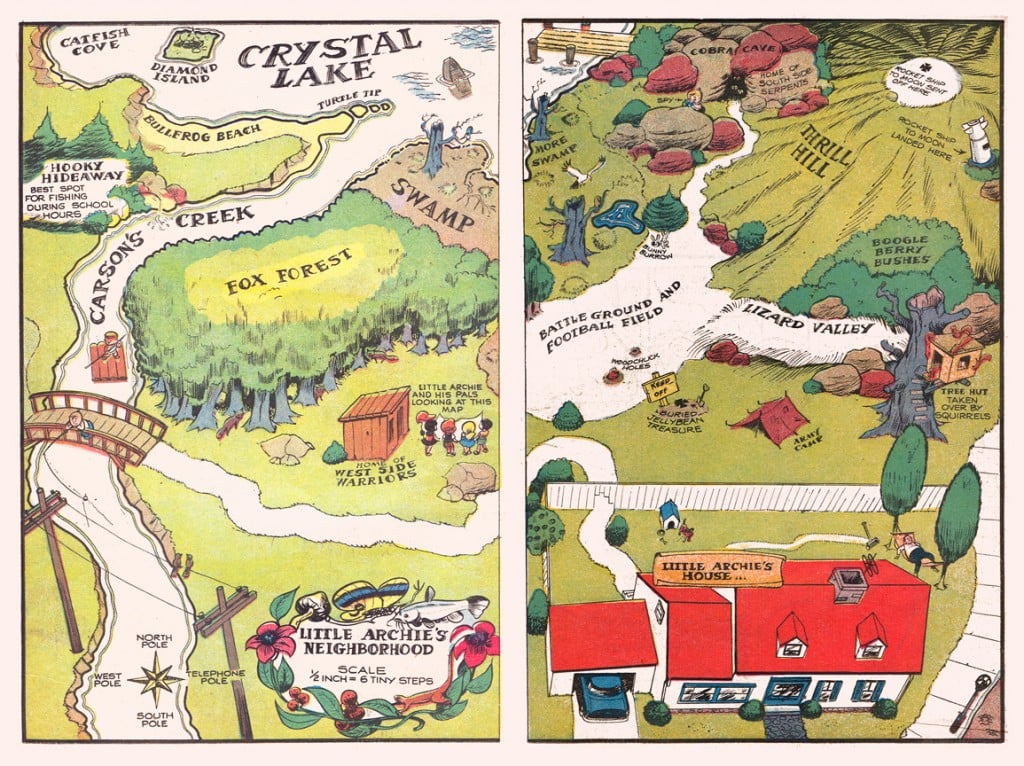

Little Archie 1-38 by Bob Bolling

If there’s an Archie artist who has the greatest claim to rank with the all-time greats, it’s writer-artist Bob Bolling, who created Little Archie for the company after the editors wanted their own answer to Dennis the Menace and Peanuts. Bolling did the expected wacky antic stories about kids in the neighbourhood, but he also turned out many other stories of an astonishing range and an unusual personal view for the Archie factory. His love of animals, his almost mystic view of nature and the changing seasons, his imaginative recreation of the place ’50s suburban kids thought they lived in, make his Little Archie stories some of the finest comics anywhere.

It’s not surprising that Love & Rockets’ Jaime Hernandez picked the moving, cringe-inducing, beatiful, mystical “The Long Walk” (Little Archie 20) as his favourite comic story. (Here’s a Comics Journal interview where the Hernandez brothers talk about meeting Bolling at a convention and embarrassing him with their fulsome praise.) This double-page spread from the story “Map Saps” is a good example of his unique blend of fantasy, nostalgia, humour and nature-worship.

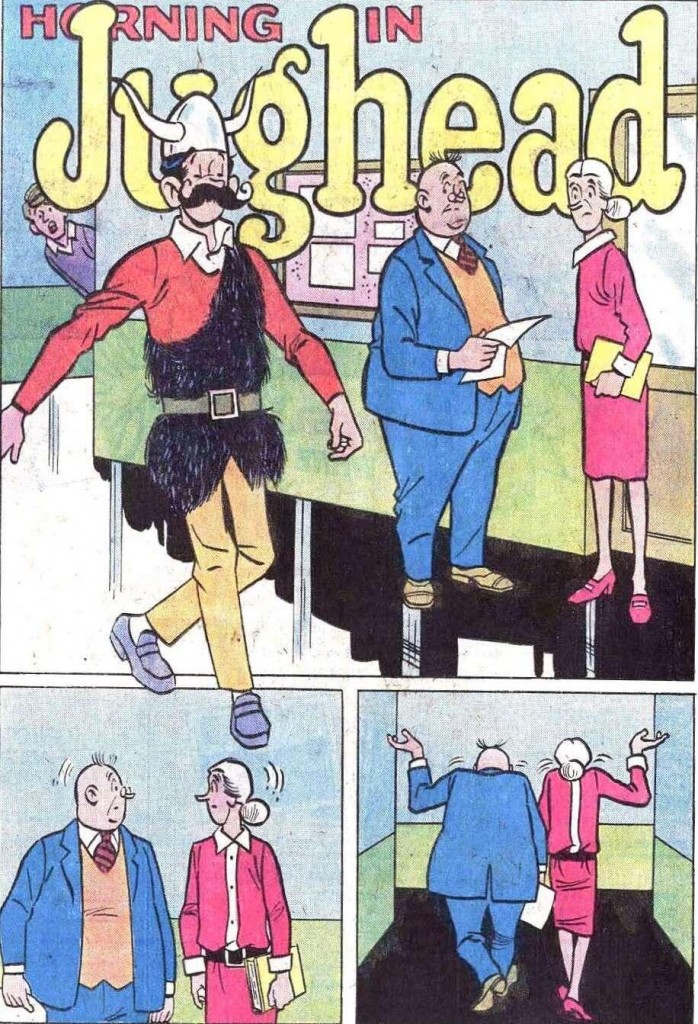

Jughead 180-300 by Samm Schwartz

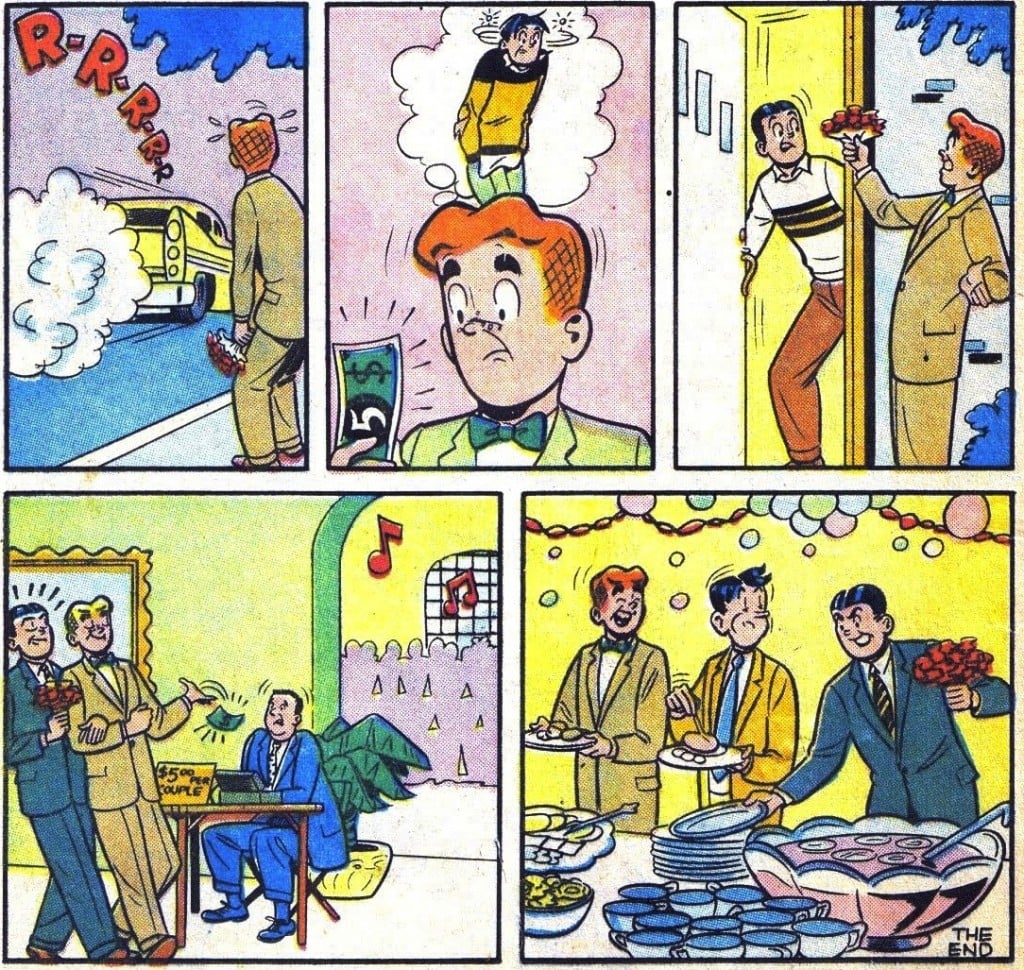

Schwartz was the first artist, after Bolling, whose name the young Archie reader actually knew, because he’d draw his name and his own likeness (sometimes with a sign saying “VOTE FOR SAMM”) into the background all the time. Schwartz was always the best Jughead artist; his absolute connection with this character, his ability to convey his combination of cleverness, apathy, charm and misanthropy should be studied by all artists to see how you achieve maximum characterization with minimal means. But his best run was probably in the ’70s, when he returned to Archie after a hiatus at other companies. He did almost all his own inks and letters by this time. With Doyle writing most of the scripts, the stories were very small — usually Jughead playing a prank on Reggie or coming to school in a silly outfit — and represent comedy minimalism at its best.

Archie by Harry Lucey

If DeCarlo is the definitive Archie artist, then Lucey is the connoisseur’s favourite. He wasn’t as prolific as DeCarlo, and though he drew the Archie title the year it outsold Superman (1969) practically no one knew his name until after he was dead. But as the primary interior artist of Archie in the ’60s and early ’70s (DeCarlo’s title was Betty and Veronica), Lucey was one of the most versatile artists in humour comics: he drew as funny as Schwartz, as sexy as DeCarlo, and had a special mastery of body language that made him especially good at silent stories.

IDW released two Lucey collections focusing on his stories from the ’60s, mostly written by (of course) Frank Doyle; it’s a good selection, including the introduction of Chris Sims’s favourite Archie character, Cricket O’Dell, the girl with the power to smell money.