The Maclean’s You May Have Missed List 2014

Our newsroom dishes on the albums, movies, books, shows, and artwork that flew under the radar in the tangle of year-end round-ups

Share

The Internet may be a big, whirling, fragmenting place—but it actually seems like most people’s best-of lists, when asked to name their favourite things in pop culture and arts, end up looking the same at the end of the year. So the Maclean’s newsroom is taking an axe to the monoculture, selecting the albums, books, movies, TV shows, theatre and artwork that our writers loved—but flew, tragically, under the radar. And we’d love to hear, too, about the stuff you loved that people just aren’t talking enough about. Join us at the hashtag #youmayhavemissed14.

Anne Kingston

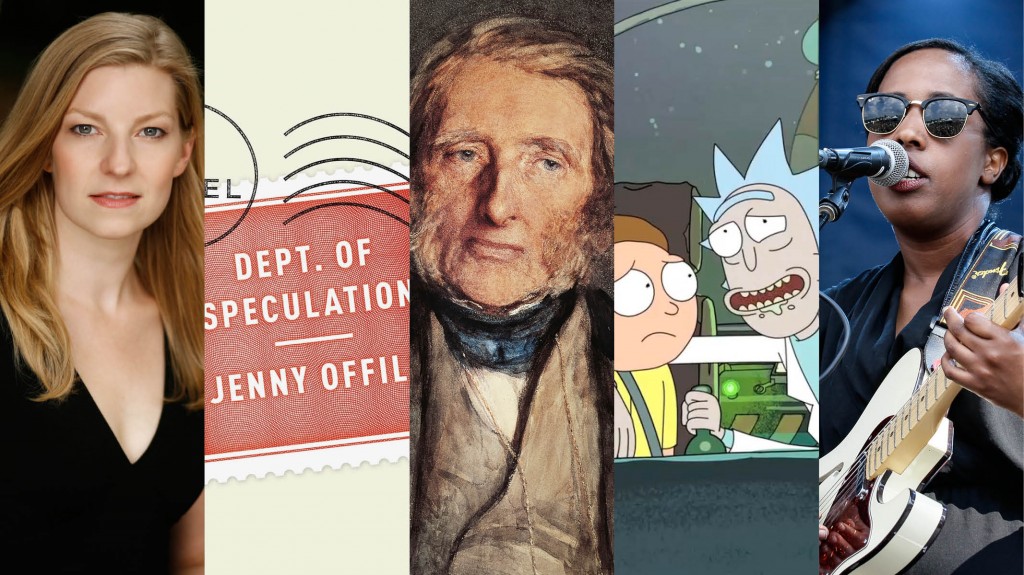

It’s not that Jenny Offill’s Dept. of Speculation didn’t get reviewed, or that many of those reviews weren’t raves. But somehow this slim book—technically a novel though its virtuosity transcends such narrow categorization—didn’t result in the ticker-tape parades or the sort of devotion accorded the NPR podcast Serial that it so richly deserved. Offill’s witty, profound, poignant rendering of marital breakdown and maternal love upends the often-denigrated “domestic” novel genre: it’s a tour de force, told via vignettes, apercus, koans and meditations that deftly reference Rilke, Darwin, Kafka, Keats, Russian cosmonauts and Zen masters without an ounce of pretension. It’s a stunning book, filled with hand-grenade truths. Once read, it asks to be returned to again and again, and to be give to people who care about reading and words—and the joy and transcendence they can bring.

John Geddes

Among the great pleasures of attending John Ruskin: Artist and Observer in Ottawa last winter and early spring, was watching the visitors move up so close to the paintings and drawings. At any moment you could look around and catch somebody leaning right in, absorbed in the fine detail of, say, a lyrical watercolour of the latticework of an old church in Venice, or somebody else nosing near enough to sniff a painted flower, or leaf, or feather, or stone. Ruskin is remembered as the great 19th-century British critic of architecture and art. But this astonishing exhibition, jointly mounted by the National Gallery of Canada and the National Galleries of Scotland, showcased his superb draughtsmanship and, more importantly, revealed how Ruskin applied that skill to expressing his devotion to his subjects, from both the natural world and the old buildings he revered. Ruskin’s name doesn’t have the marquee value of an established first-tier artist, so the show was seen by far too few—although those who did won’t soon forget its revelatory impact.

Speaking of marquee value, Colm Feore is so well established among stage actors that his King Lear was perhaps the most predictable triumph of last summer’s Stratford Festival. But who anticipated that Maev Beaty, a rising talent in Canadian theatre, would make one of Lear’s wicked daughters such an uncannily sympathetic figure? As Goneril, Beaty played up the exasperation of a daughter with her father’s dotage. You almost sided with her in early scenes, which made her later viciousness that much more unsettling.

Paul Wells

Two of the best albums this year were a reminder that challenging the audience isn’t the artist’s only option. Teaching put to audiences works too.

The great jazz record label Blue Note has gone from moribund to weird-but-intermittently-interesting since the veteran Detroit producer Don Was took the reins last year. The label produced one classic in 2014: Enjoy The View, by vibraphonist Bobby Hutcherson, who’s been recruiting odd mixes of backup instruments since the 1960s. This one has drummer Billy Hart, organist Joey de Francesco, and the surprise: saxophonist David Sanborn, here freed from R&B orthodoxy for a loose-limbed, brooding set that’s all telling gestures and strong tonalities. Each of the four players takes the presence of the other three as a licence to escape old habits.

Meanwhile, conductor Michael Tilson Thomas has built the San Francisco Symphony into a bastion of modernism and Mahler: Big serious music, either from the early 20th century or the early 21st. But there’s always been a streak of the showman in Thomas, and to mark his 20th anniversary with the orchestra he’s released Masterpieces in Miniature, a collection of unabashedly romantic short pieces from composers as diverse as Rachmaninoff, Schubert and Debussy. Nothing is longer than nine minutes. It’s all gorgeously tuneful. It’s the sort of recording that used to attract general audiences to symphonic music, and could again.

Adrian Lee

Are we veering toward peak cartoons for adults? It sure feels that way, with Adventure Time, Bojack Horseman, Adult Swim’s various offerings, Fox’s animation block, and the slew of revivals aimed squarely at tapping into Millennial nostalgia, from The Magic School Bus to Reboot to The Powerpuff Girls (come on—they’re not really making those for the kids).

Still, the almost painfully creepy Adult Swim cartoon Rick and Morty —from the combined pedigree of Adventure Time voice actor Justin Roiland and Community’s madman auteur Dan Harmon—feels essential. (Caveat: Technically, it premiered in 2013, but it largely unfolded this year.) The Back to the Future-esque story of a belching, repulsive, psychopath scientist and his imbecile grandson, it’s four steps past quirky and fully in the surreal, but so blindingly funny in parts that you’ll wonder what the big deal was with Too Many Cooks. The show is a bit of a tough nut to crack—it has innumerable gross-out qualities, including the almost aggressive weirdness of its animation style, the occasionally gag-worthy gags and some of its episodes’ dystopian warp-speed weirdness, which can be nauseating in its darker, deeper, more surreal dives—but if you catch up and cling on, especially when the episodes get a bit more comfortable and allow a little more breathing room, there’s a ton of reward. For me, its standout episode is Anatomy Park, one of its ah, simpler, ideas—Morty sent inside a homeless man’s body to save the amusement park built inside, all in what is ostensibly the series’s holiday episode—executed in such a way that only this show could have done.

As for music, I’ve already written in my top albums of 2014 list to sound the horn about the quiet brilliance of Isaiah Rashad’s Cilvia Demo EP, the Outkast-inflected, deeply assured record from the new 23-year-old signee to the label of rap’s crown prince, Kendrick Lamar. So instead, I’ll point you to the remarkable work of Canadian expat Cold Specks and her new album, Neuroplasticity. She takes everything that works from her debut revelation, I Predict a Graceful Expulsion—the muddy production, the haunting omens, and that voice, a piercing, golden thing—and lays those all upon a bed of lurching horns, dense guitars and dynamic drums, so the effect is less of an ethereal hymn that ripples like rain on puddles, and more a gospel swelling, launching triumphant typhoon waves. It’s a lovely, dense orchard of an album that deserves tilling.

Michael Barclay

How did a guitar teacher from Guelph, Ont., hook up with one of the world’s best Balkan brass bands? Normally, Adrian Raso splits his time between shredding with his rock band and unplugging with a Django Reinhardt-inspired jazz combo, but on The Devil’s Tale (Asphalt Tango) he goes toe to toe with Fanfare Ciocarlia, one of the fiercest brass sections you’ll ever hear, proving himself to be very much their equal.

I wrote about the Calgary band 36? in my earlier list of Canadian albums for Maclean’s, but I’d say the most underrated rock record from elsewhere this year was EMA’s The Future’s Void. Raised in South Dakota, now living in San Francisco, Erika Anderson started her career making avant-garde noise music; here, however, she flips between haunting and gorgeous pop songs with acoustic guitars and pianos (“When She Comes”) and snarling, synth-heavy art rock about technological dystopias—not in the future, but our selfie-obsesessed current climate, which is all the more interesting because Anderson is 27, not 72, and nothing about her album (or the fascinating multimedia web project she made to accompany it) suggests she fears technology itself, just the way it’s used to suck our souls dry (the subject of this essay). Everything about Anderson is fascinating, but it’s her voice that brings it all together. As I wrote on my full 2014 list, “Her howl is a glorious thing: not since PJ Harvey in her prime or the early days of the Yeah Yeah Yeahs’ Karen O has a female rock singer managed to snarl and scream while maintaining full control of her pitch. No tracks here sound particularly alike; this woman is not likely to run out of ideas in the near future.”

Also, to Paul Wells’s praise of Blue Note Records (see above): he fails to mention the utterly outstanding (non-jazz) album they released by Rosanne Cash in January 2014, The River and the Thread, which is hands down the finest singer/songwriter record I’ve heard in many years.

Colby Cosh

I sort of stay intentionally out of touch with popular culture, but I make an exception for the BBC. I’m a big fan of their comedy duo Mitchell & Webb, whose three-episode Ambassadors—which technically debuted in late 2013—was something of a departure, written and created by others for them to perform. I usually prefer M&W’s TV & radio sketch stuff to their Peep Show sitcom, so I am not predisposed to enjoy them so much within a proper story arc. But I’m also a sucker for Yes, Minister-type political-manners comedy. Ambassadors, featuring the pair as diplomats in a former Soviet republic, failed to make much mark: the middle episode, with Tom Hollander as a thinly disguised Duke of York, is particularly good.

I also enjoyed BBC One’s The Game, which is well-nigh a straight update of the BBC’s spy classic Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy in a Seventies collapsing-Britain setting. Tinker Tailor‘s “Circus” has become “the Fray” (with a switch from MI6 to MI5), and Alexander Knox’s crumbling, unhealthy supremo “Control” is now Brian Cox’s crumbling, unhealthy “Daddy.” But The Game is still to spot the Soviet mole before hell breaks loose. These miniseries make a good pair of bookends: they both express the particularly British thought that foreign policy may consist of the highest principles and the noblest duties, but must be implemented by ordinary, often quite weak and ridiculous humans.

Jaime J. Weinman

One of our best popular movie historians, Mark Harris’s Five Came Back tells a story of five great Hollywood directors who voluntarily put their careers on hold to make morale-boosting movies during the Second World War. He covers the frustrations that ensued when film culture met military bureaucracy, the dangers of filming the war as it happened, and how these men had changed by the time they returned. At a time when classic moviemakers are often forgotten and the Second World War often simplified, Harris reminds us of the complexities of both.

Patricia Treble

On first glance the topic—ancient Babylonian writings on flood story—didn’t seem all that appealing. Yet its deft interplay of mystery, archaeology, science and history proved so engrossing that I re-read the thick book during summer vacation. The Ark Before Noah is my favourite book of 2014.

In 1985, a man came to the British Museum with a cuneiform clay tablet from ancient Mesopotamia. Irving Finkel, one of the world’s top experts on the wedge-shaped writing, immediately recognized its opening lines: “Wall, wall! Reed wall, reed wall!” It was from a flood story, though one with a Babylonian hero, ark and animals, instead of the Biblical Noah. Finkel would have to wait another 24 years before the collector would let him launch a detailed examination of the tablet, which dates from around 1750 BCE, far older than the Genesis story. “Weeks later,” Finkel recounts, “I looked up, blinking in the sudden light.” The tablet’s 60 lines contained a detailed instruction manual on how to build an ark, as well as the most famous boarding rules for animals: “Draw out the boat that you will make / On a circular plan; Let her length and breadth be equal . . . / The wild animals from the steppe / Two by two the boat did [they enter].” Included were specific measurements—it would be about half the size of a soccer pitch—and materials; even the depth of bitumen used to seal the hull’s exterior was prescribed to be one-finger deep.

The tablet’s precise ark-construction guidelines are unique; other accounts are much vaguer in their orders. And, coincidentally, it wasn’t the first important flood-story discovery to occur at the museum. Biblical scholarship was upended when George Smith decoded the first ancient Babylonian flood narrative in 1872. Now it’s Irving Finkel’s turn to rewrite history. His passion for the long-dead Sumerian and Akkadian languages, and his love for the ancient civilization that created writing and literature—as well as beer and accounting—comes alive in a delightful, entertaining book that skilfully meanders through subjects, such as how the stories passed from Babylonian cuneiform to Biblical Hebrew and why the ark tablet demands a round boat. (It only had to stay afloat with its precious cargo, not travel.) It turns out the description fits that of a coracle, a round boat used for millennia on the waterways of what is now Iraq.

Brian Bethune

One of the Big Three literary prize shortlists included Michael Crummey and Sweetland in 2014, which is exactly two too few. Crummey is one of the finest Canadian novelists of his generation. Everything he has written has been good, most of it very good indeed, and Sweetland is his finest novel yet. It’s almost impossible to sum it up a way that’s not misleading—which may be its problem with literary juries—but Moses Sweetland, the imperious and impetuous 69-year-old last-man-standing on his eponymous island off the Newfoundland coast, is an extraordinary, beautifully realized character. (He’s not alone in that: readers really should spend some time with the feral Priddle brothers, “Irish twins” born 10 months apart.) But however absorbing Moses’s interactions with his kith and kin—not to mention the government man—Sweetland reaches its mythic and mesmerizing heights only after the others islanders are resettled elsewhere. Then Moses—a Newfoundland Robinson Crusoe who even encounters a Friday-like dog—is alone on his island, except for his ghosts, bracing for a bitter winter both seasonal and personal.

Not that good books being ignored—or for that matter dreadful ones selling like frozen peas—are unusual phenomena. One of 2014’s best and most thought-provoking views of the nuts-and-bolts aspects of modernity is Andreas Bernard’s little noticed Lifted: A Cultural History of the Elevator. There are a lot of candidates for the inanimate icon of modernity—the one object to symbolize the sea change in Western life between about 1870 and the Depression—the car, the airplane, the machine gun, even the flush toilet. Bernard makes a compelling case for the elevator.