An oral history of ’60s radicalism

Understanding today’s radicals and resisters, through an oral history of August 1969 to August 1970

Share

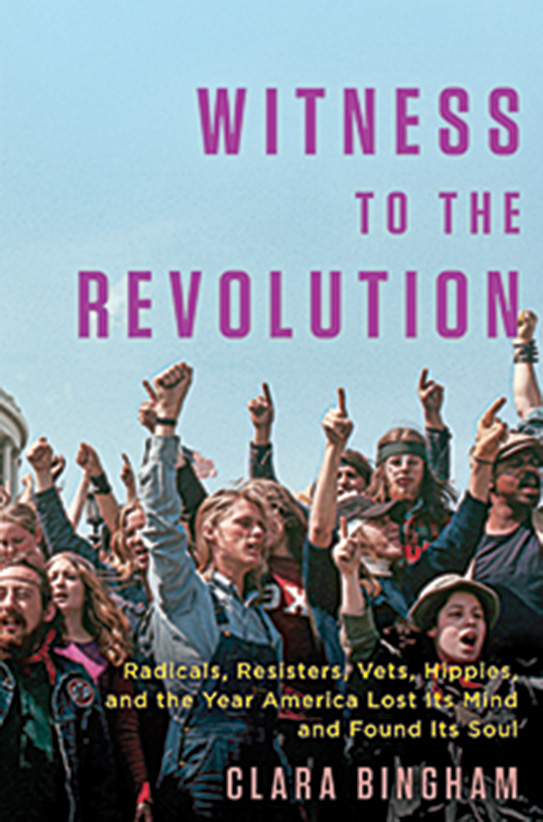

WITNESS TO THE REVOLUTION

By Clara Bingham

Today it’s Black Lives Matter, not the Black Panthers, and Edward Snowden’s NSA revelations, not the Pentagon Papers. But the core issues that motivated millions of young people in the ’60s and ’70s are remarkably similar to those driving today’s youth. This book captures the raw emotion of those earlier decades through first-hand recollections of the period from August 1969 to August 1970: the ecstasy of Woodstock, the tragedy of the Kent State massacre. Bingham interviews about 100 people, from actor-activist Jane Fonda to Watergate journalist Carl Bernstein to government officials and those who played key roles in marches on Washington and sit-ins at universities. Her brilliance is as an editor. She weaves the interviews together with only the occasional footnote or brief chapter introduction. The voices speak for themselves.

As in Howard Zinn and Anthony Arnove’s Voices of a People’s History of the United States—which presented a string of primary sources showing what some of the most marginalized people thought and wrote at the time of key historical events—there is no pretence of summarizing a tumultuous era. Bingham, too, focuses on the marginalized, as seen in her subtitle: Radicals, Resisters, Vets, Hippies, and the Year America Lost Its Mind and Found Its Soul. This is history told through the eyes of those fighting the power, and as Bingham readily admits, certain groups get more airtime than others. She touches only briefly on gay rights, the environmental movement, Native rights.

Often the memories of those interviewed conflict with each other. These inconsistencies reveal the beauty of this book: it is raw and incomplete, but all the more authentic for being so.

Witness offers many lessons for understanding today’s radicals and resisters. Things that seemed anathema to the generation that fought in the Second World War—like resisting the draft—seemed not only defensible but the moral choice to their children. The key political divide today remains generational, and for anyone wanting to understand today’s fault lines, Bingham’s book is a great place to start.