After 150 years, Alice in Wonderland remains a shape-shifting tale about how we see childhood

From 2015: Alice’s story is still a work in progress, “a blank screen onto which we project all we want to throw at her.”

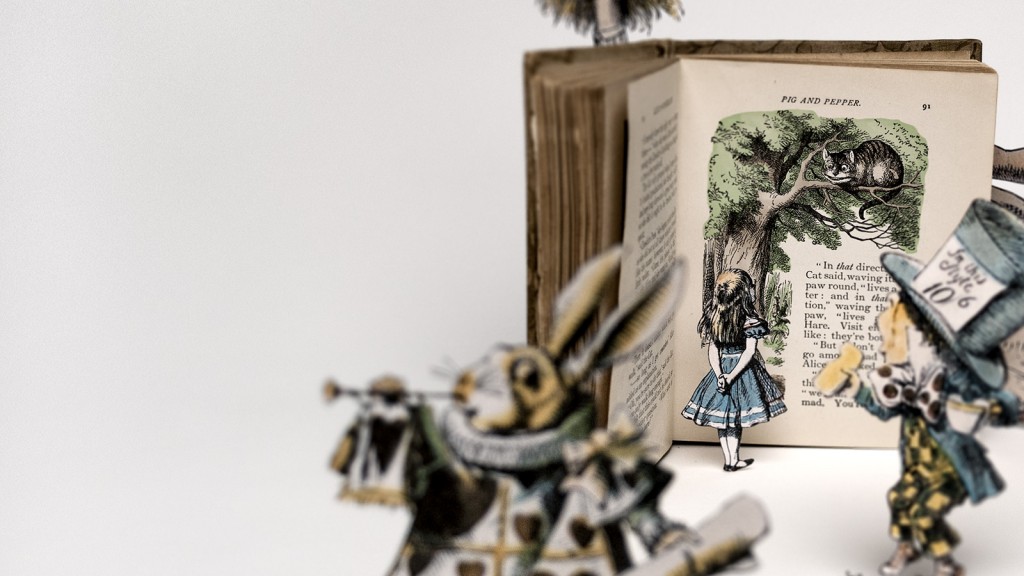

Photo Illustration by Thomas Allen

Share

This article was originally published in May, 2015, when Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland turned 150

On July 4, 1862, Rev. Charles Dodgson, an Oxford lecturer in mathematics better known now as Lewis Carroll, author of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass, rowed up the Thames to a picnic spot. He had with him four of his favourite people: his friend Robinson Duckworth and the three young Liddell girls—Lorina, 13, Edith, 8, and 10-year-old Alice. From the sparse evidence of Carroll’s diary, it was hardly a memorable occasion; perhaps it was the weather that July day: cloudy and damp, with a high of 20° C.

The embellishments began 10 months later—when Carroll went back to the entry and added, “On which occasion, I told them the fairy tale of Alice’s Adventures Under Ground, which I undertook to write out for Alice”—and didn’t stop for decades. By the time 80-year-old Alice Hargreaves (nee Liddell) was telling the tale on her triumphant visit to New York—the “original Alice” was greeted at the dock by more than 30 reporters—her recollection of a “blazing summer afternoon with heat haze shimmering over the meadows” was already established fact.

It is the perfect creation myth for a singular event in English literature—and yes: historians, recognizing it as such, have pored over the meteorological records. It’s a story that involves Carroll’s crucial place in a continuum stretching from the Victorian era to modernity, encompassing the earlier era’s near-incomprehensible—to modern eyes—concepts of childhood and of sexuality, and the birth of photography. But whatever its particulars, when Carroll finally got his story down on paper 150 years ago and published it under its now familiar title, Wonderland—a shape-shifting tale that is both a love letter to the English language and an extended metaphor for childhood—changed children’s literature forever.

Alice’s sesquicentennial—how Lewis Carroll would have loved that word—will be marked globally by events large and small. She has been published in 7,600 editions in 174 languages, including Tajik and Esperanto; many will be on display in London and New York. The popular ballet will be staged around the world, a marionette theatre in Austria will recreate the story, Vancouver Playhouse promises Alice flamenco, and on and on.

And there will be books, of course, including a catalogue raisonné of Carroll’s 1,000 surviving photographs (out of 3,000 taken). With the notable exception of Canadian writer David Day’s eagerly awaited Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland Decoded, out in September, few are liable to be as compulsively readable as Robert Douglas-Fairhurst’s The Story of Alice. The latter is informative on what went into the making of Wonderland, from the Victorians’ intense focus on the underground—both literal (the tube) and fantastic (Jules Verne’s Journey to the Centre of the Earth)—to Carroll’s anxiety about rapid change (like the Red Queen, he always thought he had to run faster and faster, just to stay where he was). And it’s brilliant in the way it mirrors Carroll’s own protean nature, offering no overarching theme, except to establish that its subject was not a man to provide two possible meanings for all he did and said, not so long as he could stuff in three or more.

Speaking from Oxford, where he is an English professor at Magdalen College, Douglas-Fairhurst makes it clear that was his aim. “I’m trying to restore a kind of innocence to biography. I don’t have strong opinions about Carroll, a man whose details are fragmentary. There is no one story, or even genre, that can give us all the answers about Alice and him. What we have are the books, masterpieces in their complexity, serious and funny, with a playful surface lying over a desperate yearning for logic and order. For 150 years, Alice has been a blank screen onto which we project all we want to throw at her.”

Nowhere is that more evident than in the murky question of sexuality, both social (Victorian attitudes) and personal (Carroll’s own proclivities). Carroll’s fans emphasize an abiding fascination with the innocence of childhood (and a hatred of change, in people, as well as circumstances); others find his interest in little girls to be borderline pedophilia, at best. Complicating the issue is the fact that Victorian thinking, militantly black-and-white in so many areas, was hazy here. There was no clear idea of adolescence yet—though one was slowly taking form—and a girl was understood to become a woman at puberty, at about age 12. That assumption, and slow changes in it, were embedded in the legal age of marriage: 12 until 1865, 13 until 1885, and 16 afterward.

There is no evidence of physical transgression on Carroll’s part—even Oxford gossip tended to pivot on the idea he was using the Liddell children to court their governess—but his mentality is another matter. It will never be settled, says Douglas-Fairhurst, because both camps find their evidence in the same place: Carroll’s photographs. Consider Alice Liddell as The Beggar Maid, a six-year-old whose ragged dress is slipping off her shoulder, exposing her left nipple. Some consider Carroll’s remark that “there are few things as effervescent as a child’s laugh” and his manifest desire, as Douglas-Fairhurst puts it, “to preserve that like a butterfly pinned to a board,” and see an artful capture of a complex aesthetic involving concepts of childhood, social class—and, overtly or otherwise, sexuality. Others, the biographer notes, see something “more like a crime scene.”

There is no evidence of physical transgression on Carroll’s part—even Oxford gossip tended to pivot on the idea he was using the Liddell children to court their governess—but his mentality is another matter. It will never be settled, says Douglas-Fairhurst, because both camps find their evidence in the same place: Carroll’s photographs. Consider Alice Liddell as The Beggar Maid, a six-year-old whose ragged dress is slipping off her shoulder, exposing her left nipple. Some consider Carroll’s remark that “there are few things as effervescent as a child’s laugh” and his manifest desire, as Douglas-Fairhurst puts it, “to preserve that like a butterfly pinned to a board,” and see an artful capture of a complex aesthetic involving concepts of childhood, social class—and, overtly or otherwise, sexuality. Others, the biographer notes, see something “more like a crime scene.”

But whatever we see, we have indeed projected for a century and a half. There is no short-form way to highlight Alice’s enduring influence. On a linguistic level alone, Carroll has few peers. He has almost 200 first use/inventor attributions in the Oxford English Dictionary. He not only invented portmanteau words that have become commonplace, such as “chortle” (crafted from “chuckle” and “snort”), he was the first to use “portmanteau”—a single piece of luggage with two compartments—as the standard term that now describes such blends.

Literary echoes ripple through Evelyn Waugh’s novels, from Decline and Fall—where one character ends up at a French brothel called Chez Alice and another is decapitated by a lunatic (“Off with his head!”)—to Brideshead Revisited, when narrator Charles Ryder comes to an Oxford lunch party, seeking “that low door in the wall,” a way into “an enchanted garden.” Even Ezra Pound, when he grew tired of endless talk about new forms of poetry, fulminated in Carrollean terms: He would take no more part, he wrote in 1917, in discussing vers libre—“ ‘ver’ meaning worm and ‘slibre’ meaning oozy and slippery.”

In the wider pools of pop culture, Alice’s after-life is even more pronounced. Why Carroll was fascinated by the number 42 is unclear, although it probably has to do with Shakespeare’s Juliet, a girl on the cusp of becoming a woman, who has to decide whether to chance a potion—just as Alice has to with the bottle marked DRINK ME—that Friar Laurence says will knock her out for “two and forty hours.” But the number resonates through Carroll’s work—one Rule 42 is proclaimed in Wonderland and another in “The Hunting of the Snark,” and there are 42 illustrations in Wonderland. Small wonder Douglas Adams chose 42, in The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, as the answer to the Ultimate Question of Life, the Universe and Everything.

Without Wonderland, there would have been no Oz; all of Dorothy’s adventures were a dream, and the major characters were based on people from her waking life. White Rabbit, the Jefferson Airplane’s 1967 megahit—which made Rolling Stone’s 2004 list of the 500 greatest songs of all time—tossed the mushroom-eating heroine right into psychedelia. As for film, there were three versions already by 1915, and Alice was literally the making of Disney. Uncle Walt came to Los Angeles in 1923 with a single suitcase bearing a single reel—12.5 minutes of a live-action-animation mix he called Alice’s Wonderland. Film distributors quickly signed up for more; a day later, he and his brother Roy formed Disney Brothers Studios. By 1927, they had produced 56 so-called Alice comedies.

It adds up, Douglas-Fairhurst judges, to more than just aesthetic influence, however massive. “Our interaction with the Alice books changed how we view children. Carroll knew how kids were hungry for what he called ‘news of fairyland,’ not for tales with morals or instruction, and were aware themselves that childhood was a garden of serpents. And we’ve learned to see children more sympathetically, as beings with lives of their own. He had such influence afterward and, even in his lifetime, so many imitations, because, to put it crudely, people realized there was a market for them.”

The Bloomsbury Group, whose works do not reveal the same straight-line influence of Carroll, were nonetheless admirers. Art critic Roger Fry came to the Alice-themed 11th birthday party of Virginia Woolf’s niece dressed as the White Knight; Woolf was the Mad Hatter. Fry later called Wonderland one of only two jewels to be plucked from the “mud” of Victorian culture’s “mawkish sentimental drivel.” Woolf was more sober—and more acute—two years before her suicide in 1941, when she summed up the Alice books as “the only books in which we become children.”