Do machines make better doctors?

What’s next, not just for society, but for suddenly vulnerable professionals? A new book examines the future of jobs

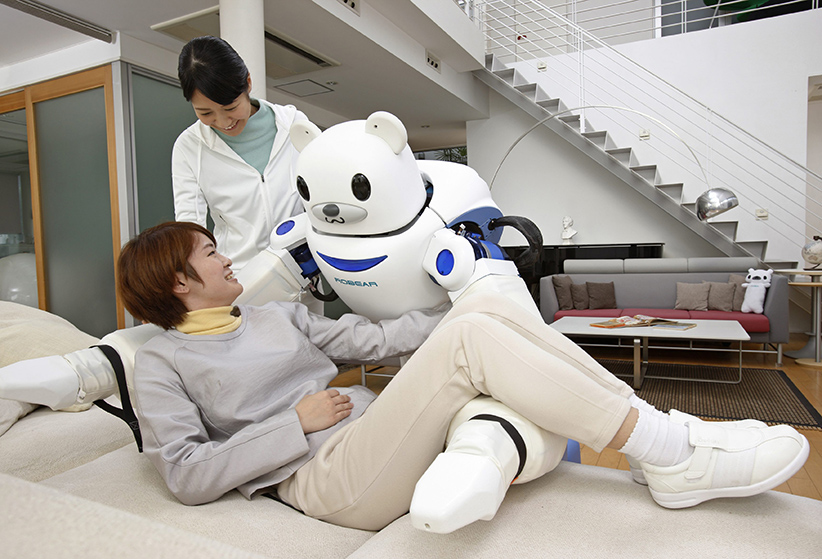

The world’s aging population could one day have robotic nursing—in the shape of a friendly bear. Two Japanese companies have joined forces to help make up the shortfall in human carers which will occur as the population ages.

(Ferrari Press Agency/CP)

Share

(Ferrari Press Agency/CP)

THE FUTURE OF THE PROFESSIONS

THE FUTURE OF THE PROFESSIONS

Richard Susskind and Daniel Susskind

The chattering classes have been paying sporadic attention for decades to the effects on people’s jobs of automation and, more recently, the Internet and artificial intelligence. (The coming of driverless cars, and the sheer number of driving jobs they will affect, is the new hot topic: traditional cab companies and Uber may soon find nothing worth fighting over.) Lately, though, intellectuals have come to realize the robots are coming for them too. For the Susskinds—father Richard, author of nine books mainly about the effects of technology on the British legal system, and Daniel, an economist at Oxford—the fact of the onrushing change is undeniable.

Already there are vast databases available online, full of medical, legal and other professional knowledge; more to the Susskinds’ point, there are computerized systems now even better than their human predecessors. The Elizabeth Wende Breast Clinic in New York found that using algorithims to scan mammograms reduced false positives by 39 per cent, and a robot pharmacist at the University of California has completed more than two million prescriptions without an error—the conservative estimate for its human peers is one mistake per 100 prescriptions or 37 million a year in the U.S. alone. And machines, of course, are cheaper.

What the authors call the Grand Bargain—by which the gatekeepers of expertise provide their services to laymen in exchange for status, deference and steady occupation (if not always riches)—is crumbling before our eyes.

So what’s next, not just for society, but for suddenly vulnerable professionals? There is a real risk that new gatekeepers, possibly more mercenary than the past ones, will control the flow of information. The Susskinds are optimistic this will not happen, and that civilization will immeasurably benefit from a kind of professionalization of us all. As for actual professionals, their altruistic side—many think of their work as a vocation as well as source of income—will flourish, as they will be able to spread their expertise farther than ever. And there will be new disciplines, most noticeably involving those who can encode professional knowledge into software.

But incomes and status will inevitably suffer. The only possible parallel that comes to the minds of the authors (and most readers) is the fate of master craftsmen after the Industrial Revolution: most faded away. Not all, though: there are still bespoke tailors and instrument-makers around today—even if only the wealthy can afford them—and there will always be some elite professionals. Would humans ever allow machines to make the choice to terminate end-of-life care?