Fictionalizing the accounts of women in the Second World War

Book review: ‘The Race for Paris’ reimagines the swashbuckling journalist Martha Gellhorn’s adventures in the Second World War

Share

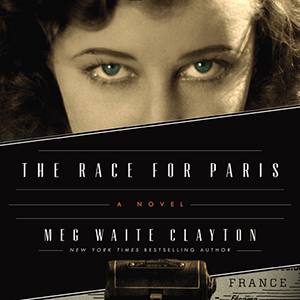

THE RACE FOR PARIS

Meg Waite Clayton

Some stories of life on the Second World War’s front lines are deeply ingrained in the public imagination, kept alive by a bottomless well of cultural offerings, from The Longest Day to, say, Band of Brothers. But accounts of women are rare still, and quite forgotten are the stories of the female journalists who did their best to outwit the period’s “no broads allowed” sexism and to finagle their way to the front: women like Life magazine photographer Margaret Bourke-White, the first to be officially allowed to work in combat zones, and Collier’s magazine’s Martha Gellhorn, who hid on a D-Day hospital ship to cover the landings. Like photographer Robert Capa, she ended up on Omaha Beach. Ernest Hemingway, always chivalrous, once sent a cablegram to Gellhorn, wife No. 3: “Are you a war correspondent or wife in my bed?”

Clayton fictionalizes these experiences in The Race for Paris through the stories of a glamorous war photographer, Liv Harper of Associated Press, and Jane Tyler, reporter for the Nashville Banner. Like their real-life counterparts, they want to be where the action is—in this case, the American liberation of Paris—and make their names with the first photos and stories. A Pulitzer is the goal. Their partner-in-stealth (and romance) is a charming British photographer. Pursued by military police on orders of Liv’s husband, an influential newspaper editor in New York, they sleep in barns and file their work anonymously, lest they be discovered.

The anonymous reports are a delicious metaphor for the invisibility of women. Casual misogyny held female journalists back: No latrines for women at HQ meant they couldn’t attend the army’s daily briefings; they were banned from combat situations. To disobey the rules could result in a loss of accreditation, house arrest or, worst, being sent to England. Nevertheless, women like Gellhorn—and Canadian Press correspondent Margaret Ecker and Vogue magazine photographer Lee Miller—persisted. Clayton, who wrote the bestseller The Wednesday Sisters, incorporates cameos from real-life personalities—from The New Yorker’s A.J. Liebling and CBC journalist Matthew Halton, to Eleanor Roosevelt, who regularly wrote to female journalists to encourage their work.

Beyond the love triangle, the book illustrates a fundamental tension found in all wartime: Journalism, whether by men or women, was an essential part of the propaganda effort, with censors (and editors) making sure newspaper stories and images would not upset readers at breakfast, but it encouraged support of the war. No photographs of the faces of “our” dead boys in situ were allowed, a tradition that continues.