Friendship, and the bond between women in their 30s

Emily Gould’s debut novel explores the difference between being an adult and being grown up

Share

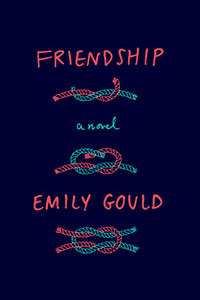

FRIENDSHIP

By Emily Gould

There’s a difference between mere adulthood, which is legally defined, and being a grown-up, which is fuzzy and subjective. For the characters in Gould’s funny and affecting debut novel, this difference is sharply felt. Broadly a coming-of-age story, Friendship explores the bond between two women entering their 30s as they face personal and professional frustrations and the nagging sense of being stuck in a protracted adolescence.

Bev and Amy have been best friends since they both worked as assistants at a publishing house. An aspiring writer, Bev finds herself employed at a temp agency after dropping out of an expensive master of fine arts program. Amy, once a semi-famous blogger, works at Yidster, “the third-most popular online destination for cultural coverage with a modern Jewish angle.” They live in New York City, which they can’t afford, and pass their workdays “G-chatting” and texting. When Bev finds out she’s pregnant and Amy confronts unforeseen transitions, the dynamic of their relationship shifts, as they must decide, separately, what it means to grow up. Complicating matters is Sally, a wealthy woman whom Bev and Amy meet and whose presence adds an awkward layer to their strained friendship.

The novel’s depiction of the dynamics of friendship—how there’s often affection and admiration mixed with envy and competition—feels authentic. Gould’s prose reads like the voice of the charmingly blunt friend you wish you had; her observations are hilarious and insightful. The portrayal of office ennui is depressingly accurate: Amy spends her time reading Wikipedia and checking Twitter, while Bev, collating papers, has a “flash of wanting to smash something made of flesh, her own hand or someone else’s.”

There’s a long tradition of novels about bright young women hoping to conquer New York. Many of these books culminate in glamorous self-actualization, but Friendship refuses this path. These characters must will themselves past disappointment and realistic problems—precarious finances, especially—and they don’t end up where you’d expect. What they choose—it’s the act of choosing that means everything—is as surprising as it is satisfying.