How beauty from the brush of Claude Monet was born from war

A captivating new book describes how Claude Monet painted his placid scenes with First World War shells sounding in the distance

Water Lilies, 1916 by Claude Monet. Found in the collection of the National Museum of Western Art, Tokyo. (Heritage Images/Getty Images)

Share

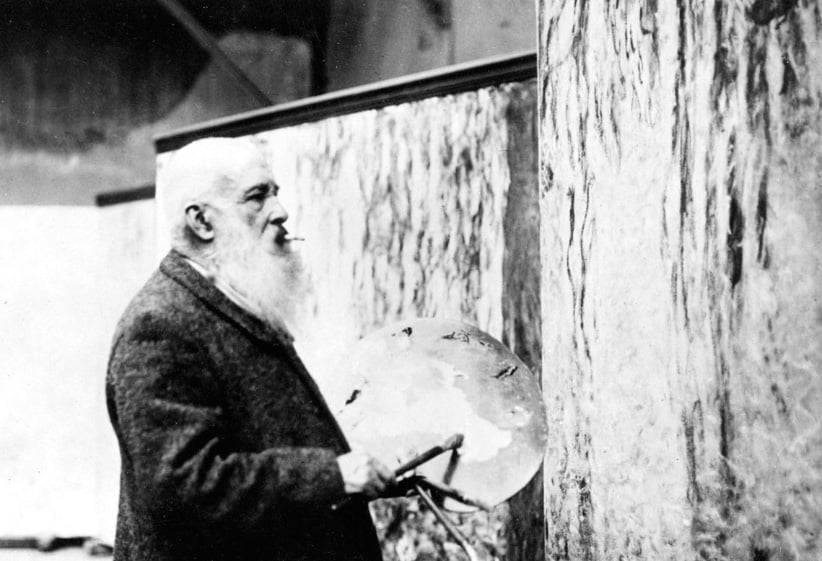

In early September 1914, after tens of thousands of French soldiers had already died in a war only a month old and the French government had fled to Bordeaux, 73-year-old Claude Monet was feeling defiant. “I shall stay here regardless,” he wrote from his home at Giverny outside Paris, “and if those barbarians wish to kill me, I shall die among my canvases, in front of my life’s work.” It’s an arresting, lion-in-winter image, and the sort of moment in art history that has always intrigued Ross King.

The bestselling author from Estevan, Sask., now resident in Oxford, has been here before. In such books as Michelangelo and the Pope’s Ceiling (2002) and Leonardo and The Last Supper—the latter of which brought him the Governor General’s Award and a nomination for the RBC Taylor Prize in 2012—King has “drilled deeply into the artistic instances that interest me the most,” he says in an interview. “I want to unpick those moments, maybe reverse-engineer the works of art, whether it’s Michelangelo in the Sistine Chapel or Leonardo in Milan, to see how the process unfolded, because the artists had to adapt, make difficult decisions. It’s never clear until the very end whether they’ll even finish the job, let alone produce masterpieces.”

That’s certainly the story of Monet and his Water Lilies, the explosive cap—some 350 sq m of canvas—to an already glittering career, and the subject of King’s Mad Enchantment, shortlisted for this year’s $25,000 RBC Taylor Prize. Various currents were intersecting in the life of Monet and France. The painter’s beloved wife had died in 1911 and his celebrated vision was threatened by cataracts; he rarely took up his brush before the spring of 1914, only months before the Great War began. With wartime supply restrictions, three members of his family in uniform and the sound of artillery audible in Giverny, added to the sorrows of his old age, it would have been easy for Monet to have packed it in. Instead, says King, he began to view the lilies as “war paintings, his war work,” and contribution to the national cause—in no small part because of the urgings and help of his oldest friend, Georges Clemenceau, once and future prime minister of France.

Mad Enchantment could have been called Claude and Georges Go To War. “Clemenceau is absolutely vital to what is a buddy story in some ways,” says King. “They went way back together, to the 1860s, and in early 1914, Clemenceau went to Giverny to shake his old friend out of his depression. Clemenceau—who was to prove himself capable of rallying the entire French nation—got Monet back to work.” Clemenceau, famous for his demonic energy, also found time during the war to ensure Monet was supplied, encouraged and convinced to donate his last works to France. “Monet could not have done what he did without Clemenceau,” King adds. “When he grew frustrated with his efforts, sometimes slashing his canvases, you can tell by his writings that one of the things that brought him back to the work was he didn’t want to disappoint his old friend.

Both men survived the war and can be counted, like France, among the victors. Clemenceau was there at the end too, ensuring the paintings went into a state museum after Monet’s death at 86 in 1926 (Clemenceau, then 85, lived another three years.) The first reviews were terrible, notes King, after an exhibition opened in 1927, with critics calling Monet’s impressionism outdated. They didn’t see, the author says, the evolution of Monet’s art, how his impressionism had become almost abstractism. It took a new generation of modern artists flocking to view the Water Lilies after the Second World War to restore the reputation of late Monet to equal status with early Monet, with the painter’s “war work” recognized as among the world’s artistic masterpieces.

An excerpt from Mad Enchantment

“Monet paints in a strange language,” the reviewer had claimed in 1883, “whose secrets, together with a few initiates, he alone possesses.” This language was understood much better by the first decades of the 20th century. Impressionism in general, and Monet in particular, had been the subject of numerous books and articles explaining their secrets: the seemingly impulsive brushwork and random compositions of everyday subjects of middle-class leisure and beautiful but otherwise undistinguished snatches of countryside. As early as 1867, readers of Edmond and Jules de Goncourt’s novel Manette Salomon were given, through the depiction of a painter named Crescent, a clear-sighted account of the aspirations of Monet and his friends. Crescent differs from the members of the “serious school,” who are “enemies of colour.” These painters, trained at the École des Beaux-Arts, distrust spontaneous impressions and instead approach paintings “by reflection, through an operation of the brain, through the application and judgment of ideas.” Crescent, by contrast, instinctively records his sensations of grass and trees, the freshness of a river, the shade along a path. “What he sought above all,” the narrator says, “was the vivid and profound impression of the place, of the moment, the season, the hour.”

This passage gives a remarkable account of what was soon to become Monet’s practice. But how were these scenes—with their subtle and often short-lived visual effects such as quavering leaves, fleeting shadows and glints of light—to be reproduced by pigment on canvas? How could the immaterial and impermanent be given materiality and permanency? How could the artist capture what the human eye perceived in the brief sparkle of a second?

The technical procedures of the impressionists varied from painter to painter, and in most cases they evolved over the decades. But their “strange language” involved, among other things, conspicuously calling attention to their brushes and their paints. They fragmented their brushstrokes into flickering touches of colour that seemed to dissolve their painted worlds into shimmering mirages. Most critics and gallery-goers were taken aback by these apparently slipshod and incoherent dashes and commas, which were so different in application from the smooth and precise touches of established and successful painters, such as Meissonier, whose meticulous attention to minute detail was savoured by one collector through the lens of a magnifying glass. Impressionist canvases were not meant to be seen at such close range. In 1873 a young critic named Marie-Amélie Chartroule de Montifaud, who wrote under the pseudonym Marc de Montifaud, noted that the apparently “crude simplicity” of a Manet painting actually disguised a sophisticated visual experience. “Stand back a little,” she urged in her review. “Relations between masses of colour begin to be established. Each part falls into place, and each detail becomes exact.” The ideal viewing distance for Impressionist paintings soon became a topic of scientific discussion. Camille Pissarro—who by the 1880s had hoped to use “methods based on science” in his art—eventually came up with a formula whereby the viewer should stand at a distance measured at three times the diagonal of the canvas.

Paradoxically for a painter who wished to give the impression of spontaneity, Monet’s painting technique actually required a good deal of forethought and groundwork. His supposedly impulsive canvases were actually the result of much advance preparation and fastidious organization. A visitor to his studio once counted 75 paintbrushes and 40 boxes of pigments. Each of his canvases—which arrived regularly on the train from Paris—was first of all primed with a layer of lead white, giving a luminous ground for the layers of bright colour that he would then apply. One of the innovations of Édouard Manet and the impressionists in the 1860s had been this pale, luminous base layer on which they worked. Their technique broke all of the artistic rules established by the “serious school,” since artists had always painted over top of a darker ground in order to enhance the appearance of depth. Titian and Tintoretto, for example, had used brown or dark red undercoats, and even Gustave Courbet—a good friend of Monet’s and an early influence on him—sometimes painted over a black primer coat. But the impressionists in their quest for an airy brightness abandoned not only these dark bases but also the bitumen-based glazes with which so many of their predecessors had slathered the tops of their painted canvases in order to achieve a darkish Old Master patina. As a connoisseur once informed John Constable: “A good picture, like a good fiddle, should be brown.” Many colour merchants even stocked for use by painters the same amber glaze with which instrument makers varnished their lutes.

Those who prized the well-varnished Old Master look were highly suspicious of colourful pyrotechnics. The 19th-century art theorist Charles Blanc once declared that painting “will fall through colour just as mankind fell through Eve.” But the impressionists had been only too happy to be seduced by the bright new colours that 19th-century chemistry was creating. Early in his career, Monet had captured the sparkling effects of sunlit water on the Thames thanks to a palette that included cobalt violet, invented in 1859, and chromium oxide green, created in 1862.

Monet was also anxious to use pigments that would survive the test of time—ones that would not fade or yellow, as he knew so many pigments were prone to doing. According to an art dealer, Monet was always thinking about “the chemical evolution of colours” as he painted. By the time he resumed work in the spring of 1914, his palette of colours had therefore been narrowed to those pigments he believed to be the most stable. In order to enhance their preservation, he also mixed them much less than he had done in the 1860s and 1870s. Moreover, he took to squeezing his pigments onto absorbent paper to extract some of the poppy oil binder, since he knew that oils, as they rose to the surface, were responsible for the yellowing of many Old Masters—a murky posterity from which he hoped his paintings would be spared.

Excerpted from Mad Enchantment by Ross King. Copyright ©2016 Ross King. Published by Bond Street Books/Doubleday Canada, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited.

Reproduced by arrangement with the publisher. All rights reserved.