Q&A with George Saunders: ‘Art is not some inessential frippery’

One of the great American writers of his generation discusses U.S. politics, the power of books, and his late friend David Foster Wallace

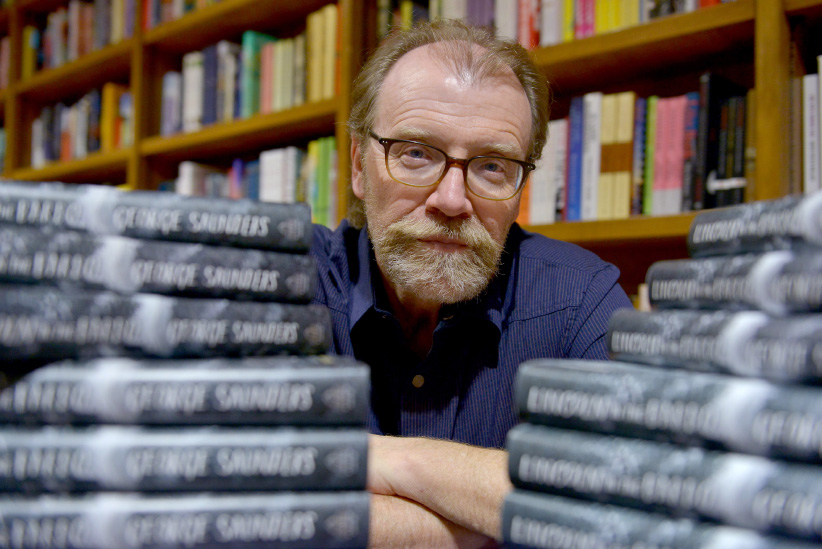

Author George Saunders, reads from his new book “Lincoln in the Bardo” with the help of (L-R) Cristina Russell, Gaël LeLamer, Viv Evans, Cristina Nosti and Katherine Wakefield at Books and Books on February 19, 2017 in Coral Gables, Florida. (Johnny Louis/FilmMagic/Getty Images)

Share

George Saunders’s Lincoln in the Bardo is one of 2017’s most celebrated books, written by by one of the greatest American writers of his generation. During the first, bloody year of America’s Civil War, President Lincoln’s son Willie falls ill, and passes away. Reportedly, the distraught Lincoln visited his 11-year-old’s Washington cemetery crypt several times the first night he was there, to be with his son. Saunders imaginatively and stirringly conceives a graveyard chorus of diverse voices as Willie remains in the Bardo, the Tibetan transitional zone.

I spoke to Saunders on a recent American afternoon, over the phone. (Later that evening, he was performing a reading of Lincoln in the Bardo with Kitchen Dog Theater’s “soulful badasses” at the Dallas Museum of Art.) He spoke to Maclean’s about his New Yorker feature story on American politics, U.S. aggression, Donald Trump, Bernie Sanders, the power of literature, and the legacy of his late friend David Foster Wallace. This interview has been condensed and edited.

Q: Abraham Lincoln got intense criticism during the epoch in which Lincoln in the Bardo is set. The Civil War is going very badly, and he’s suffering a lot. He has become more empathetic. Is that a takeaway for our troubled times?

A: When you’re out there in America, meeting with regular people, it’s a pretty mellow, relaxed, kind-hearted country. The direction from the top, from the President, is following mean-spirited tendencies: fear and undue caution and distrust of the other, so it’s very depressing.

I’ve been talking a lot on the road about empathy, and about how the most powerful thing is trying to imagine the person you’re resisting. Not because it’s lovey-dovey, but because it’s effective. If you’re in a football game, if you could mind-meld with the opposing coaches, that would be an incredible way to make your team more powerful. I think this whole literary game of trying to put yourself in the shoes of your opponent is good for everybody. It leaves you more open-hearted, it gives you a more accurate vision of the other person, because it’s more based on curiosity than projection. In the end if you do have to fight, you’re better equipped to fight. Also it doesn’t leave you damaged at the end, it doesn’t leave you hateful or malformed by your own anger.

Q: Colson Whitehead, who wrote the novel The Underground Railroad, told me last year before Trump won: “Their chickens are coming to roost, it’s gratifying to see how the GOP has destroyed itself; unfortunately, they’ll probably drag us down with them. So the arc of justice bends ever so slightly, but we’re all going to pay the price for their twenty years of foolishness.”

A: As much as we—in a revisionist way—tell ourselves that we’ve always been a righteous country with a couple of swerves off the path, we need to look back and see that we’ve always also been a racist country and have had a tendency towards banal aggressiveness. The thing that’s alarming is not so much that a few people at the top are initiating these crazy policies, but that the middle is willing to go there too. There’s a strange movement of the middle to this position of banal aggressiveness.

So far it’s been a bit alarming in the way that that middle population who maybe didn’t vote for him, or voted for him pulling their noses, haven’t really deserted the ship yet. We’re in some uncharted waters right now, so I’m trying to be a little uncertain about this stuff because it’s changing every afternoon.

Q: You had cordial conversations with Trump supporters covering his campaign for the New Yorker, but no one was able to persuade anybody about anything?

A: Exactly right. There was one woman who said to me, very earnestly, “Do you liberals really believe that the Government should run every aspect of our lives?” And I was like, “No”. It was shocking to see the division, but it certainly wasn’t scary.

There were people that were doing violence at these things—not to me—but the vast majority were just there. I’d expected to see a bunch of crazy people, based on what I’d seen on TV, but it was just normal people. Very happy to talk, very civil. That should have been maybe my first clue that it was a bigger movement than we expected.

Q: Some of Trump’s supporters are marginalized Appalachians and Deep Southerners, but obviously he’s got lots of rich, powerful, elite supporters.

A: Yes, that’s right. Months of stories said that he was elected by suffering white working and lower middle-class workers, but that just isn’t entirely the case, you know? There are certainly lots of working and lower middle-class people of colour who didn’t vote for him. So it really is a complicated, multi-headed thing that’s going on. But my feeling is: Let’s keep our eye on the groups that are suffering the most under him– immigrants, and Muslims, and women–let’s put those at the front of the line.

But if we consider “compassion” as meaning the desire to not see anybody suffer, then a compassionate approach to the current moment might also include some thought for Trump supporters too, of course there are the middle- and lower-middle-class people who suffered under these last thirty years as the money went up and up—the phenomenon that Bernie Sanders describes. Even the person who’s a Trump supporter who, for whatever reason, is advocating these harsh policies—at some level that person’s suffering too. He might be suffering economically and if he is advocating policies that hurt other people, he’s suffering that way too, whether he knows it or not. As a writer, that’s my challenge: to not slide over into dogma or simple anger and try to keep all these different boxes open.

Q: Do you think Bernie Sanders would have won?

A: What did the Trump movement come out of? It came out of something which many liberals and conservatives can agree on: that over the last thirty years, the money just went up. The money left the lower-middle class and the middle class and went up to the mountain top. If you imagine America, spread out on a mountainside … well, all the oxygen went up to the few at the peak, and all those sufferers—the middle class and lower-middle class sufferers on the side—are living in essentially an anaerobic condition. Not having enough oxygen makes people anxious. So that’s what Bernie saw, in a very truthful and humane way. It’s also what Trump saw, in a deeply cynical way, and he combined it with his nationalism or whatever you want to call it.

I know what it feels like to be in that middle and lower-middle class, and feel like the culture is passing you by; it translates into a great sense of personal frustration that can then morph into political frustration. That goes back to the idea you were talking about earlier, about the materialist tendency in American culture. Now the money’s going to go up even faster than it used to, and the people who Trump was supposedly rescuing are going to be the ones who get hurt the most.

One of the things that I noticed with the Trump supporters is they had that catch phrase for Bernie: “Oh, he’s a socialist!” And a catchphrase in the wrong hands can do a lot of damage, like “Crooked Hillary.” I think Bernie could have won because he was so honest: what he believed, he said, and what he said he believed. I heard him give a speech in Flagstaff. I’ve heard a number of speeches in my life, but this was one where everything he said was right on, made 100 per cent sense to me. It was like he was plucking out the best part of my mind and saying it out loud. So I think he could’ve won; and if so, we’d be in an amazing situation right now. There were probably 15,000 people at that rally, most of them young people, totally fired up. I think that energy is still there.

Q: The Republicans are proposing gutting the National Endowment for the Arts. The budget for that is $148 million a year. The cost of security for Trump Tower for American taxpayers, meanwhile, is $183 million a year. How can we protect the NEA?

A: It’s really such a ridiculous and critical moment, one that was presaged by the constant campaign mantra about the country needing a businessman to run it. A country doesn’t need a businessman to run it: it needs a heartful, worldly, compassionate leader. That is, someone who understands that a culture is its arts. Art is not some inessential frippery—it is the nation’s means of intelligently regarding itself. To cripple or stigmatize the arts is to doom one’s nation to a life of incuriosity, dullness, literalness and the worst kind of rank materialism. I think maybe it’s time for a second big march on Washington: a March for the Arts.

Q: Are there any lessons from the Lincoln era for our current political moment?

A: Well, a good one is: “A house divided against itself cannot stand.” What’s dividing us: partisan media. What can bring us back together?

I think we need leadership that can gently and with affection remind us of what we Americans mostly agree upon: civility, kindness, tolerance, humour, et cetera. The current administration seems to thrive on trying to enforce a very odd, fearful agenda, that it tries to disguise in a false garment of fondness for the working-class—despite the fact that its policies seem designed to continue the decades-long habit of marginalizing that group.

Q: What do you think Lincoln would make of Paul Ryan? Ryan says kicking millions of people off healthcare is “an act of mercy.”

A: It’s hard to know what Lincoln would think of any of this. For my part, I think Ryan and his ilk are swimming in a weird soup of 1980s, trickle-down, Ayn Rand-inflected ideas that seem to indicate not much interaction with or understanding of the actual underprivileged. They would, of course, say otherwise, and claim that their policies are ultimately good for the lower-middle and lower classes. What I don’t understand is the elaborate measures they take to avoid saying, simply, that it is a disgrace for Americans to be avoiding going to a doctor just because they can’t afford it. That is pretty simple stuff. What would, for example, Jesus say? I think He would say that these are our brothers and sisters and that it should break our hearts to go to our doctor when someone else, sick, is unable to go to his or hers. Dress it up as you like, it’s a failure of compassion, and it’s shameful.

MORE: Reza Aslan on how religion intersects with the Democrats and Republicans

I know this will sound naïve, but I often wonder what America would be like if our national ethos was simply to minimize suffering. Period. To try, every day, to convert our wonderful wealth and national energy into the cessation of suffering wherever we find it. Imagine if that was our national mindset, rather than whatever it is now—”Don’t tread on me,” or “Get thee away from mine” or “Here’s to a deeper trough with fewer of us feasting there.” Well, we can—we must—dream.

Q: What shouldn’t liberals do?

A: As a lifelong progressive, one thing we do is the liberal flinch, where we feel somehow like second-class citizens. Especially after this election, there was a big mea culpa moment that liberals went through: “Oh, we didn’t imagine the heartland well enough”. That’s probably true, but the Trump supporters aren’t imagining us either. Had Hillary won, I don’t think the Republicans would be beating their chests, going, “Oh, we have been unfair to those liberal folks in the city.” What we don’t want to do is confuse an empathetic response with an innately wimpy response—the kind of liberal loser where when somebody drives a spike through your head, you go, “Thank you so much for the coat rack”.

Q: Do you hope people reading Lincoln in the Bardo will become more empathetic?

A: That’s the kind of thing that you tend to say in interviews—and I hope that’s true. I think that in general that’s what literature does. It tenderizes the reader in some way. That’s a beautiful, soul-expanding thing. But, of course, the other truth is that I don’t know how many people on the Trump campaign are turning to novels. Some are, I suppose.

Q: Lincoln in the Bardo’s audiobook has quite the cast: 166 voices take part, including Ben Stiller, Julianne Moore, Bill Hader, Jeff Tweedy, and Don Cheadle. How does an audiobook add a different dimension?

A: I was so wonderfully isolated writing the book for four years, obsessively trying to figure it out. I had a really hard time breaking loose of that historical period and of Lincoln. The audiobook, a deeply collaborative thing, was a really nice stepping stone back into the contemporary world.

When I’m writing a book, the different places in the book result in very specific images as I am re-reading. Listening to the audiobook, that changed. I would hear somebody’s interpretation and suddenly a different image would hit me, or a different feeling. When Keegan-Michael Key read his part, I was really moved by it. When I wrote it, that part was maybe more of a prose experiment, mostly textural. When he read it, I really felt the human being on the other side of it.

Q: Lincoln In the Bardo evokes a moving sense of mortality. What do you hope your late friend David Foster Wallace’s legacy is?

A: I hope people will turn again and again to his work, because I don’t know a wiser, or more original, or more honest thinker. That was always my experience with him. I’d be around him and suddenly I’d acutely feel all the different kinds of falseness in me. He was someone who was not comfortable with lying. I think his influence is maybe stronger now than it was when he passed away. Young writers love him. I wish I could talk to him about this Trump thing, because he always was twenty percent ahead of the curve, and he had that sort of relentless logic that would lead him to a truth that the rest of us would stumble upon a couple of years later. I so wish that he was still with us. He was also a very dear person, very loving, and was becoming more lovable and loving and funny and wonderful every day. I miss him.