In conversation with Jamie Oliver: Why Britain really is great

The U.K. chef opens up about his latest cookbook and why he’ll never tire of talking about food

Share

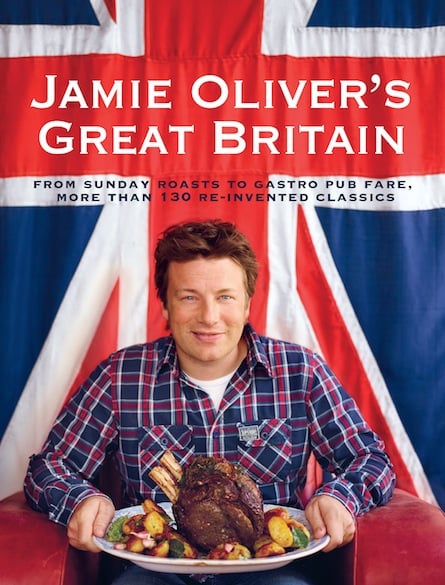

After travelling through Italy and America and pegging TV shows and books to their respective food cultures, Jamie Oliver turns to his home and native land. His latest book, Jamie Oliver’s Great Britain, is a beautiful ode to the gastronomy of the U.K. And if you love culinary history, the tome does an incredible job of reminding readers that Britain was once a top-notch leader. Thanks to young people with an interest in food (and Oliver himself, if you ask me) things are looking better than ever after that 50-year mid-20th century comestible blip.

After travelling through Italy and America and pegging TV shows and books to their respective food cultures, Jamie Oliver turns to his home and native land. His latest book, Jamie Oliver’s Great Britain, is a beautiful ode to the gastronomy of the U.K. And if you love culinary history, the tome does an incredible job of reminding readers that Britain was once a top-notch leader. Thanks to young people with an interest in food (and Oliver himself, if you ask me) things are looking better than ever after that 50-year mid-20th century comestible blip.

Oliver will be in Toronto to promote his book, and a six-part television series attached to it, on October 19 at Massey Hall. The $49.50 to $99.50 ticket price tag to attend includes a copy of Great Britain, which I can’t seem to stop reading.

We had the chance to ask the chef via email about his latest–and very patriotic–project.

Q: I’?m reading a book right now that chronicles the evolution of cooking using the history of kitchen techniques and tools. A chapter on roasting focuses on British food historian Ivan Day and his passion for Victorian spit-roasting roast beef. The author tries it and writes, ?So this is why there was such a fuss about the roast beef of England.? In a sense, your book is performing a similar service of reminding folks that Britain used to cook food that people talked about. What did British food mean to you growing up? What does it mean to you now? What do you want it to mean in the future?

A: I never realized how lucky I was growing up in my parents’ pub until I was older. They served proper British food, always made from fresh ingredients, cooked from scratch by cooks who cared. My parents cared about good food. My mum’s Sunday Roast is still my favorite meal of all time. With this book, I wanted to share all of the amazing chefs, producers and artisans all over my country who are retracing old recipes, rediscovering great local ingredients and focusing on simplicity and quality.

Q: After travelling extensively through both Italy and the U.S., you?ve probably seen first-hand how classic Italian dishes were, for better or worse, reinterpreted by Italian-Americans over several decades. New dishes–?think penne alla vodka, spaghetti and meatballs, and veal parmigiana?–were born. Do you think the same gastronomic migration has happened with British food? Best examples? Worst?

A: Good question. The immigrant food in Britain hails from India, Yemen, and Jamaica. We have the most delicious curries and jerk seasonings available to us. Sure there can be bad curry—really bad curry, but most of the food is delicious and I was lucky to experience it. I’ve included a Roasted Veg Vindaloo, that I learned when I visited a Goan community in Leeds and the lightest, most interesting Yemeni pancakes that I learned from some ladies in Cardiff’s Tiger Bay as well as a Mulligatawny Stew and a killer jerk pork from the boys in Bristol.

Q: You mention in Great Britain that young people play a big role in the revitalization of good cooking, and eating, in the U.K. What do you think it says about our era that food is a creative force that rivals the novel, music, etc. in attracting bright young minds?

A: It’s funny really. When I was learning to be a chef, it was a job you got because you weren’t good in school. Cooking was the only thing I did really well—I guess I could drum and draw too, but cooking was my thing. Now, everyone is excited about food—cooking, growing, learning—watching it on TV, buying books, trying things at home. It’s the greatest time ever to be in food—which is why it’s so hard to see so many people still relying on processed food. I am hoping that we had a generational blip—and that these young people will continue on and pass on their love of food and creativity to the next generation of kids.

Q: You also make a point of highlighting in the book the influence of other cultures in what many perceive to be classic U.K. dishes. Take fish and chips, for example. Is there a concern that as the world becomes increasingly homogenized, food culture will suffer? Do you think it accounts for the renewed interest in slow, local and traditional?

A: I think food culture is always evolving, and there will constantly be people looking both forward and back. That’s what makes it exciting. As a chef, I want to serve the best possible dish made from the best possible ingredients to the public for the best price. In my books, I want to inspire people and teach them how to cook for themselves.

Q: Accolades can be hard to receive, but bear with me: maybe more than any other chef in the international spotlight, you have a heck of a lot of moral credibility. You put your money where your mouth is. And you manage, with every cookbook, the magazine, the restaurants, the TV shows, to stay sincere, humble and most importantly, you maintain this incredible enthusiasm when it comes to food. But do you ever wake up in a cold sweat at night and think, ?Christ, is it all too much?? Do you ever get tired talking about food?

A: Wow, that is some question. Thank you. I think. I never get tired of talking about food. I do getting tired of fighting governments when they are so clearly not putting the best interest of the children forward.

Q: A restaurant in Toronto (The Grove) dedicated to cooking nouvelle British food recently earned a spot in our magazine’?s Canada’s Best Restaurants Guide. Is authenticity important to you with your homeland?s cooking (as it is to, say, the Italians?) And is there a go-to British dish that you?’d order to measure the chops of a restaurant serving British food outside of the U.K.?

A: It’s great to know about The Grove because awards like this one mean that British food is being taken seriously in other countries, whereas when I started 14 years ago, British food was a laughing stock, pretty much. I think authenticity is important whichever homeland you’re from but one of the lovely things about British cooking is that we adopt great food and dishes from all of the lovely people who come from overseas to live in our country. We’re a magpie nation – we take the best bits of other cuisines and embrace them as our own. As for my go-to British dish – it’s a tricky one but if you can do a good slow-roast like a shoulder of pork, then you’re doing well.