Maclean’s picks the best books of 2016

Our books writer Brian Bethune reveals his unranked list of his favourite reads of 2016

Share

Every year, Maclean’s picks the best in arts and culture. To read more of our selections of what shone in music, television, movies, and books in 2016—as well as our annual Missed It List, capturing the items that went under the radar—go here.

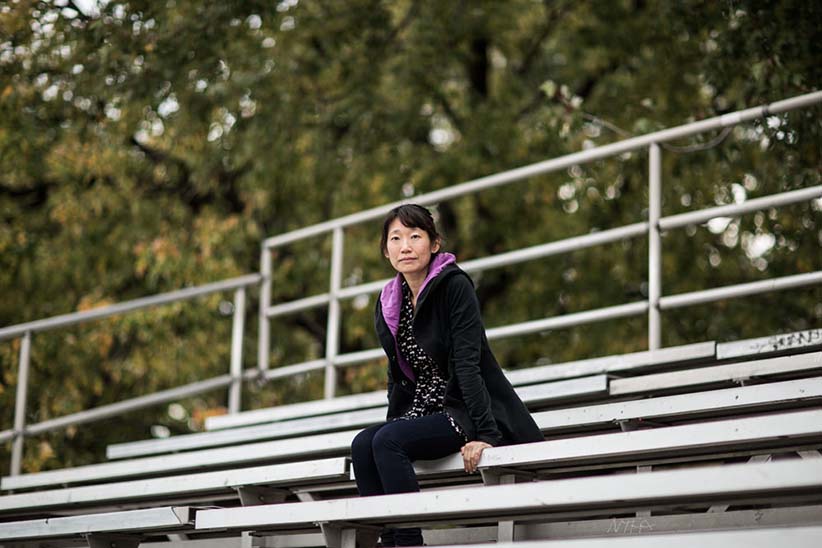

Do Not Say We Have Nothing. Madeleine Thien’s novel is one of 2016’s most acclaimed, and deservedly so. In it time moves forwards, backwards and even sideways in a graceful exploration of how people have more than one identity, and nothing ever happens just once. There is no optimism here, but Thien’s exquisitely written story of two families and two oppressive eras in China provokes a paradoxical hope.

Being a Beast. Charles Foster, veterinarian, lawyer, philosopher and (unsurprisingly) Englishman, details how he has tried to live like a beast. For the book, Foster dwelt underground in a badger sett for weeks on end, munched on earthworms, ate out of trash bins like an urban fox, and grew his toenails for months to be a better red deer. It’s all aimed, he says, at becoming a better human. It’s part rigorous science, part boys-playing-hobbits adventure, part sheer madness, and wholly absorbing: it’s one of the year’s most astonishing books.

The High Mountains of Portugal. There really isn’t anyone else in CanLit quite like Yann Martel. After the reader-alienating Beatrice & Virgil, his new novel offers a thought-provoking and hugely appealing take on his signature themes: the wafer-thin and permeable wall between animals and people and the superiority of story to mere facts in creating human reality.

Orwell’s Nose. A happy conjunction of author (John Sutherland, who has lost his sense of smell) and subject (Orwell was obsessed with scents and with crafting “smell narratives”) makes this superb, self-described “pathological” biography an huge contribution to understanding the English writer.

The Hidden Life of Trees. German forester Peter Wohlleben’s account of anthropomorphized trees—they talk to each other, learn from experience, feel pain, nurse sick neighbours, lavish love on their children, and even at times take care of their dead—infuriates scientists and utterly charms everyone else who reads it.

The Adjustment League. A literary thriller of stabbing insight that’s often corrosively funny, Mike Barnes’s novel features the Super, who cycles in and out of mental illness very much as Barnes has done for his entire adult life. The Super keeps a rundown Toronto apartment building going in exchange for cheap rent; on the side, he makes tiny, perfect “adjustments” in the lives of the unjustly marginalized.

Waiting For First Light. Readers derive no more pleasure from reading this post-Rwanda memoir by Roméo Dallaire, Canada’s public face of PTSD, than he found in writing it. But his story is brutally informative of the ravages of the disorder when left untreated, and the risks to which we continue to subject our soldiers.

The Money Cult. Chris Lehmann’s eye-popping history shows how the genius, the presiding spirit, of American religion has always been the same as the genius of American capitalism. It’s always been a money cult, with prosperity a sign of salvation and poverty something to self-help your way out of.

Nothing Ever Dies. Viet Thanh Nguyen’s memoir cum meditation on the hard search for mutually “just” image of a conflict, is simply the most penetrating, and beautifully written, book on war and memory yet seen in the 21st century. All wars are fought twice, Nguyen notes, once on the battlefield and again in memory.

News From the Red Desert. A medical doctor, Canadian Forces veteran and volunteer at the Canadian-run combat surgical hospital at Kandahar in 2007, novelist Kevin Patterson understands soldiers, combat and chaos, and part of him loves them all. That’s why this clear-eyed story of best-laid plans and the triumph of random chance is so austerely compelling.