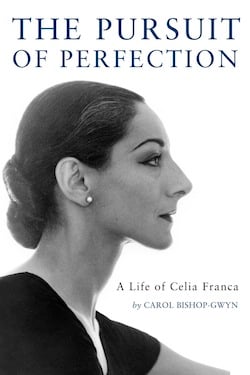

Presenting Charles Taylor Prize nominee Carol Bishop-Gwyn

Plus an excerpt from her biography on Celia Frank, the founder of The National Ballet of Canada

The Globe and Mail

Share

Although she didn’t know it at the time, Carol Bishop-Gwyn, as a dance-enthralled little girl in Toronto—and the proud owner of an autograph of British ballerina Margot Fonteyn, no less—was part of Celia Franca’s moment in Canadian cultural history. Still enthralled by dance, and now the possessor of two postgraduate degrees in dance history, Bishop-Gwyn, 65, is the author of The Pursuit of Perfection: A Life of Celia Franca. Shortlisted for the Charles Taylor prize, as well as the Governor General’s Literary Award, it’s a biography of the driven Englishwoman who founded the National Ballet of Canada.

The postwar years were one of ballet’s golden eras in the 20th century. As a distraction from the horrors and deprivation of the Second World War, dance “boomed in Britain,” Bishop-Gwyn notes. The Sadler’s Wells company, for which Franca danced, “trooped around the country for 50 weeks of the year,” drawing packed houses. “Of course, the British companies couldn’t cross the Atlantic then, but when they did after the war they caused a sensation.” Bishop-Gwyn still recalls seeing the Sadler’s Wells dancers “shivering on a stage built over the ice rink at Maple Leaf Gardens.” Dance exploded in popularity here too—Bishop-Gwyn’s own lessons, taken “before it became abundantly clear I was not ballerina material,” were one tiny part.

The Pursuit of Perfection captures the response of the Toronto of the day, just beginning its transition from large, straitlaced, Orange Lodge-dominated town to sophisticated, multicultural city. (Cocktail lounges were daringly legalized in 1947.) Booming economically but feeling culturally deprived, and oriented—among its elite—to the mother country, English Canada as a whole and Toronto in particular looked for British help. For better or worse, and the National Ballet’s ongoing international stature argues strongly for the former, Franca was available.

Then 29, she was charismatic, abrasive and ruthlessly ambitious—not just for herself but for the company she envisaged. And she was larger than life: from the moment she stepped off the plane in February 1951 in her black Persian lamb coat, with pencilled eyebrows, white makeup and hair pulled tightly back, Franca was a cultural icon in this country. “She never let down her guard,” Bishop-Gwyn says, “never stepped out of her role.”

Some who knew her think Franca, who refused to speak of any unpleasantness encountered in her professional life, would not have wanted a biography, let alone Bishop-Gwyn’s warts-and-all take. The author, however, notes that Franca donated to the archives a huge collection of personal papers, including, literally, her laundry lists: “I don’t think she’d have liked to have seen aired some of the things I’ve written about, but I think she would have been happy with the acknowledgment: she taught Canada how to dance.”

Very early in the game, Celia had shrewdly figured out an important part of the Canadian character: a cultural endeavour needed to receive praise from the United States or Great Britain before Canadians themselves would give it any recognition. Celia had gambled by taking her dancers to a festival primarily devoted to modern dance. And she had to endure [modern dance pioneer Ted] Shawn’s admonishment or, as she described it, “his usual disgusting speech to students and audience that it was shameful that Britain and its Dominion had no modern ballet.”

Having been well received in Jacob’s Pillow [Shawn’s Massachusetts arts festival], and after touring extensively throughout Canada in 1954, Celia raised the bar. In 1955 she convinced the board to sign up with the New York-based William Morris Concert Agency to tour through the United States every second year, mostly on the circuit of college and community centre venues. But she had had to fight hard.

Earlier that year the board had provoked a showdown over finances and insisted on cancelling several bookings, including one at the Brooklyn Academy of Music. Celia rushed back to Toronto to confront the board, arguing that the engagement at the prestigious BAM was too good to be missed. She berated them, “The theatre is all gamble, and if you don’t gamble you’re through.” One board member commented, “We won’t die if we don’t go to New York.” Celia shot back, “That’s just where we disagree. I think we’ll die of slow rot if we don’t expand. If we get good notices in New York we’ll get other bookings and more people at home will come to see us when they see we’re accepted in the States.”

The board, unconvinced and unprepared to gamble away any more money, challenged Celia to raise $9,000 in two days. The target was virtually impossible. But Celia, with Betty Oliphant as her ally, set out to get that money. Over two days, the pair cold-called everyone they could to solicit a donation.

As Maclean’s reported afterwards, Oliphant phoned a woman she had never met who asked, “Don’t you think you have a nerve taking the company to New York?” Betty retorted, “No, I don’t. I think they’ll be a credit to you and to me.” The stranger donated $500. The dancers themselves turned in $10 of their own pittance of a salary, while various members of the Canadian Association of Dance Teachers chipped in. In all, $5,000 was raised. At this point, [lawyer and Tory political fixer] Eddie Goodman asked a senior executive at Cadillac Constructing and Developments Ltd. to make a matching donation. As Goodman explained in his memoirs, “I pounced upon its president, Eph Diamond, and his partners, Joe Berman and Jack Kamin, and extracted $5,000 of their meagre profits, which got the company to New York and back.” The target had been exceeded by $1,000.

The tiny but formidable Celia Franca, with the help of Goodman, had called the board’s bluff, but the episode had exasperated Celia. Tolerance and patience were not her strong suits, as she would demonstrate time and again. A Maclean’s article touched on her short fuse. “After one such meeting a guild director complained to Betty Oliphant: ‘I’ve had just about all I can take from that woman. Today she called me a bloody fool.’ Betty reproached Celia. Celia denied the charge. ‘I didn’t call him a bloody fool, I’m sure,’ she said. ‘Maybe I called him a fool.’ ‘Bloody fool sounds more like you,’ Betty Oliphant observed. ‘Well, I wouldn’t call him that unless I really liked him,’ was Franca’s closing defence.”

Celia’s triumph in getting the $9,000 meant that her company did go to New York’s Brooklyn Academy of Music in March. As an added coup, Celia presented Tudor’s Offenbach in the Underworld, with the choreographer sitting in the audience. The National Ballet’s two appearances attracted other notable ballet luminaries, including Lucia Chase, co-founder of the American Ballet Theatre, along with ballerinas Alicia Markova and Nora Kaye. The major New York dance critics came to check out this upstart Canadian company. Celia had proved to her timid board that their company could compete in the international ballet world. This success led to the company going to Washington that June to open the season at the Carter Barron Theatre, a large outdoor stadium.

Excerpted from The Pursuit of Perfection: A Life of Celia Franca by Carol Bishop-Gwyn, published by Cormorant Books. Copyright © Carol Bishop-Gwyn, 2011. Reprinted by permission of the publisher.

The Charles Taylor Prize for Literary Non-Fiction, which recognizes excellence in Canadian non-fiction writing, will award $25,000 to the winning author on March 4.