Remembering the sad, odd, writerly life of Roberto Bolaño

Book review: Mónica Maristain’s ‘Bolano: A Biography in Conversations’

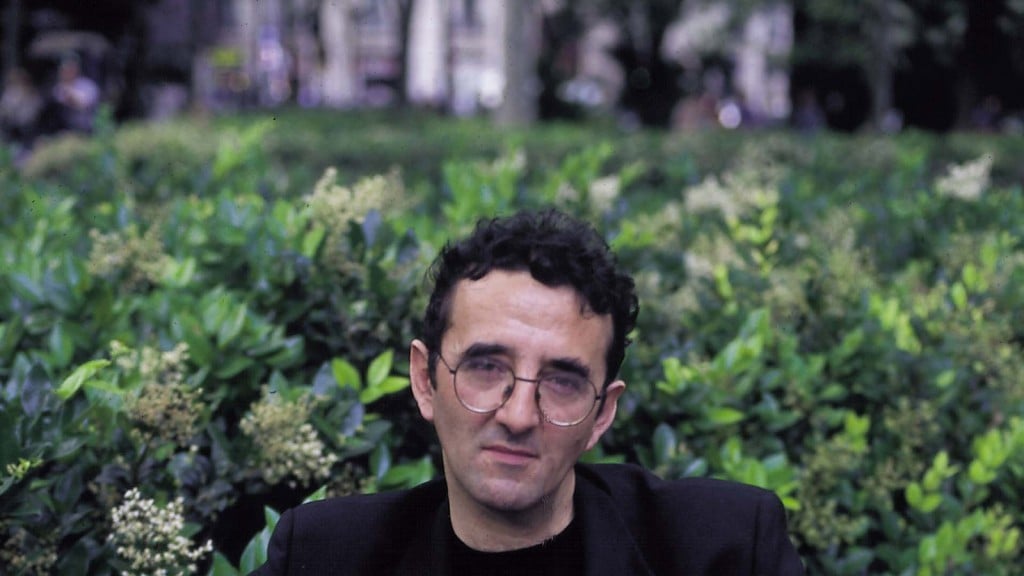

Roberto Bolano. (Luzphoto/Getty Images)

Share

BOLAÑO: A BIOGRAPHY IN CONVERSATIONS

BOLAÑO: A BIOGRAPHY IN CONVERSATIONS

Mónica Maristain

In this first-ever biography of the acclaimed Chilean novelist Roberto Bolaño, a picture emerges of a writer whose childhood eccentricities developed into a fearless drive that was bent on fighting mediocrity with frank talk that earned him enemies. His widow, Carolina Lopez, remembers a passionate man who was unable to forgive disloyalty.

Bolaño died at age 50 of liver disease in 2003, while second in line for a liver transplant. The New York Times reported him as a drug addict, but the book ends with a confirmation from Bolaño’s liver specialist that his disease wasn’t related to alcohol, nor to heroin, a drug Lopez confirms that Bolaño never took.

The author’s posthumously translated epic novels 2666 and The Savage Detectives received rave reviews from top critics such as Janet Maslin and James Wood, and comparisons to Jorge Luis Borges and Gabriel García Márquez.

His last interview was with Argentinian journalist Maristain, who, afterward, spoke with his friends and family. Bolaño’s father, Leon, a professional boxer and truck driver, remembered his son as an unusual kid who took walks and read a lot, and showed no interest in money. “Sometimes I gave him five pesos and he said to me: ‘No, that’s too much. Give me two.’ ”

Bolaño didn’t do well in school, often talking back to teachers and correcting them. His father remembers a teacher calling to say, ‘Your son is right, but tell him not to say so in front of others, because it makes the teacher look ridiculous.’ In Mexico, Bolaño was expelled from school for the same know-it-all attitude that caused him trouble in Chile.

Bolaño went on to form a literary group of outsider writers known as the Infrarealists. “What brought us together,” remembers a poet, “was the desire to blow the brains of the official culture.” Bolaño was critical of authors of “beach books”—easy to read and lucrative for publishers, but offering little critical meaning to the reader. His outspokenness bruised the feelings of writers like Isabel Allende. “[Writers] always expect compliments, but Bolaño wasn’t going to go around handing out compliments,” one friend said. Publicly, Bolaño denounced Allende as a “scribbler” and later became famous for declaring, “Don’t be sparing with your flattery of idiots . . . if you don’t want to spend some time in hell.”