Sarah Bakewell takes us drinking with the existentialists

At The Existentialist Café showcases Bakewell’s knack for writing smart, gossipy reads on heady subjects

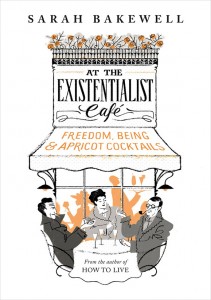

At the Existentialist Cafe

Share

AT THE EXISTENTIALIST CAFE

By Sarah Bakewell

Sarah Bakewell has a knack for writing smart, gossipy reads on heady subjects. Her 2010 biography of Montaigne was a surprise hit and won a National Book Critics Circle Award. Now comes her group portrait of Jean-Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir, Maurice Merleau-Ponty and other European philosophers who emerged in the years between the world wars. At The Existentialist Café covers a lot of ground, and one of Bakewell’s narrative gifts is to place existentialism and its sister school of thought on subjective experience, phenomenology, in historical context. Both philosophies flowered in the rubble of the 20th century. After the large-scale devastation of war, depression, another war and the bomb, is it any wonder these thinkers yearned for some sense of individual purpose?

This was the era of classic existential texts. Sartre, while a prisoner of war, read Heidegger and developed ideas of personal freedom that would find their way into Being and Nothingness. Albert Camus, active in the Resistance, published The Stranger and The Myth of Sisyphus, both notions of bleak absurdity. Indeed, Bakewell almost makes occupied France sound like a metaphor for existentialism itself: “Everyday life required constantly negotiating this balance between submissiveness and resistance, as well as between ordinary activity and the extraordinary underlying reality.”

After the Second World War, continental existentialism was exported to the United States. American critics swooned over Sartre and de Beauvoir. The pair became celebrity intellectuals, free in their thinking, fast in their habits. They espoused free love and engaged in cocktail-fuelled debate at jazz clubs. Never before had deep thoughts been expressed with such Parisian verve. Interestingly, Bakewell notes that despite the initial exposure of these brainy bon vivants, the enduring public perception of existentialism differed on either side of the Atlantic. In France, the philosophy was considered “new, jazzy, sexy and daring,” while its American adherents were pale pessimists who lurked in noirish streetscapes. Perhaps something was lost in translation. Consider, even today, this clichéd black-and-white photo of a man standing in the shadows: trench-coat collar turned up, cigarette drooped down. Is it Camus or Bogart?

This discrepancy could in part be attributed to the French “fondness for potboilers about hit men and psychopaths.” Hardboiled writers like Dashiell Hammett and James M. Cain carried the stigma of low culture back then, but based on their lonely protagonists’ struggle to make sense of a dark world, these penny-a-word proletariats were their country’s original existentialists. De Beauvoir certainly found one of their ilk sexy and daring. After the “rather unsuccessful” sexual aspect of her relationship with Sartre had ended, she wrote in her memoirs that she experienced her first orgasm with Chicago tough guy writer Nelson Algren. It was the ultimate consummation of ideas.