In-Between Days offers a deeply affecting memoir

Teva Harrison offers a poignant account of living with cancer

Share

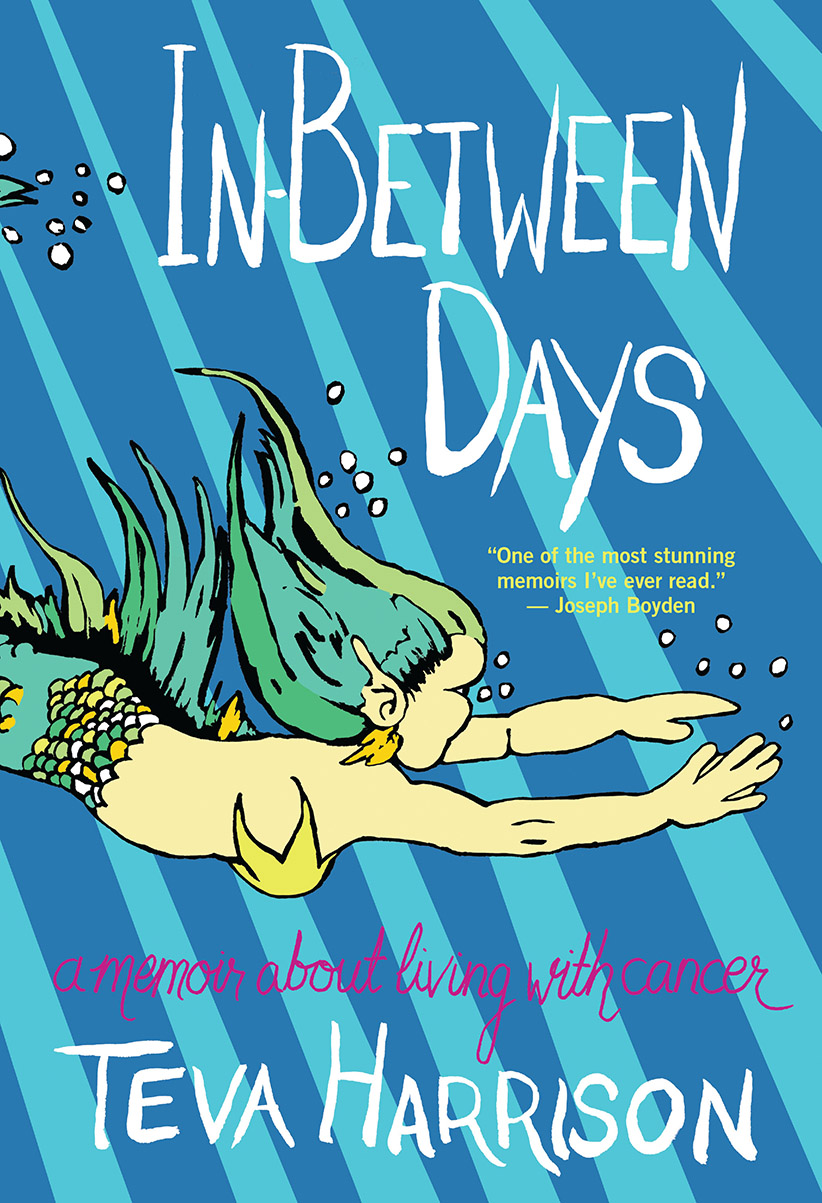

IN-BETWEEN DAYS

By Teva Harrison

For people who have a serious illness, rhetoric can be a real . . . well, cancer. In an Atlantic article from 2014, an American physician fretted about whether military-inflected words like “fighter” had “done more harm than good” when his aunt was dying of lymphoma. “I refuse to believe my death will be because I didn’t battle hard enough,” wrote Kate Granger, a U.K.–based doctor with cancer, in a piece for the Guardian that same year.

“The most truthful way of regarding illness—and the healthiest way of being ill—is one most purified of, most resistant to, metaphoric thinking,” wrote Susan Sontag in 1978, when she was undergoing cancer treatment. Nearly four decades later, it’s a challenge to follow that counsel—in part because martial language and overblown symbolism have (if you’ll excuse the phrase) invaded our cultural understanding of disease. But in her deeply affecting new memoir, Teva Harrison offers an alternate strategy.

In 2013, at the age of 37, Harrison, a Toronto artist and author who was working at an environmental NGO, was diagnosed with metastatic breast cancer, which has an average prognosis of two to three years. To make sense of what she was going through, she began documenting her thoughts in a series of compelling, emotionally candid black-and-white comics. In-Between Days (the title refers to the purgatorial ethos that colours her life) pairs those with frank written anecdotes about everything from her sex life to her family’s health history to her awkwardness around small talk (“There’s a type of person who’s desperate to talk about cancer: people who want to process the death of a loved one”) to animate the halcyon highs and excruciating lows involved in navigating a terminal illness.

Harrison’s drawing style is more freeform than finicky, and her linework has an appealing vulnerability. But even beyond that aesthetic quality, there’s a remarkable directness to seeing vignettes from a life coloured by cancer that cuts to the quick. In the shower, Harrison lathers thinning hair, the result of surgically induced menopause; in a tender moment, her husband waltzes her around the house, her feet balanced on his; in a flashback scene, she recalls her child self at the bedside of a beloved, gaunt-faced aunt wasting away after a mastectomy. The results are profoundly, achingly affecting.

The story here isn’t a new one, even in Harrison’s own family tree: woman receives devastating breast-cancer diagnosis, endeavours to live her best life. What’s striking is, as Sontag might say, her resistance to metaphoric thinking. There’s whimsy, to be sure: the author and a friend don tails and sequins and march in a mermaid parade, and Harrison conjures childhood summers spent stargazing and having flower-petal snowball fights. But when it comes to the day-to-day details of cancer, Harrison is unflinching in her efforts to tell—and show—the straight story. It’s not a battle; it’s simply a state of being.