Penis thievery and other strange syndromes

The Geography of Madness maps the roots of suffering

Share

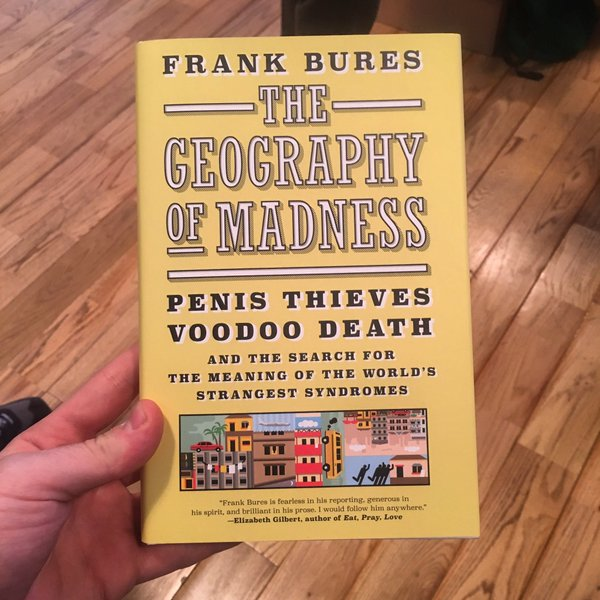

The Geography of Madness

By Frank Bures

In 1990, Frank Bures spent one year in Italy as a high school exchange student and never quite recovered. What stuck with Bures was the culture shock: the realization that the standard American songbook of Levis, football and fast food wasn’t the only way to live. So began his career as an award-winning travel writer.

This book harnesses his wanderlust into an investigation of “culture-bound syndromes.” Those are maladies that most Western minds, with our biomechanical view of the body, dismiss as superstitious nonsense. Take the epidemics of magical penis thefts in Nigeria, Singapore, China and India in the 1960s and mid-1980s. Or the sudden madness called “amok” in Malaysia. What about “fugue” wandering syndrome in Europe in the 1800s? Or the more recent “sudden unexpected nocturnal death syndrome” among Vietnamese refugees in America, among other groups?

Bures asks what forces are at the root of people’s suffering. How is mental and physical health intertwined? Along the way, readers get an entertaining history of the study of culture, and a chronicling of the breakthrough experiments about the placebo effect and its opposite, the nocebo effect: a negative reaction brought on by imagined exposure to a treatment. Bures is at his best when explaining things like a bioloop, where mental and physical states are connected so that each alters the other in a circle of causation.

But there is bound to be controversy over Bures’s identification of America’s culture-bound syndromes. He points to anorexia, repressed memory syndrome, hoarding and PMS as things that don’t exist in other countries. Carpal tunnel syndrome, he asserts, can’t be explained in purely mechanical terms, but is partly shaped by something in our culture. (My osteopath vehemently disagrees.) He’s right to question the legitimization of seemingly American-only maladies by their inclusion in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), but these are the weakest chapters, by far—more dry, less confident and with shakier footnotes.

Bures makes up for it with plot twists. He drops bombshells from his own family history that give the story heart and make his quest more meaningful. As for stolen penises, he concludes it’s not a disease or a delusion, but something in between. Still . . . watch out for the fox ghost.