What the endangered Great Bear Rainforest has to teach us

Wolves, salmon and bears can teach us about self-sacrifice and ecology

from the publisher. Great Bear Wild by Ian McAllister. Wolf in the wild.

Share

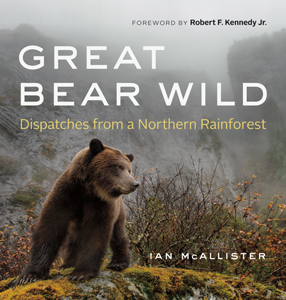

GREAT BEAR WILD

Ian McAllister

In the most haunting scene in conservationist Ian McAllister’s new book, a family of grey wolves chase a pack member, “snarling, biting and pushing” into the cold ocean off B.C.’s central coast. With no escape possible, “he is forced to half dive, half lunge from the cliff into the frothing white surf.” McAllister, also a talented photographer, aches for the animal, whom he has observed since it was a pup. (He’s spent more time with these wolves than his own family; building trust, as he writes, requires a long-term commitment.) Through his grief, McAllister recognizes he is witnessing the most crucial and difficult decision an alpha leader must make: “The pack had reached its carrying capacity, especially as pups would soon be near adult sized and capable of joining the hunt. In wolf society the pack cannot live beyond its means: someone had to go. How this individual was chosen only the pack will ever know.”

The Great Bear Rainforest’s wolves, salmon and iconic, white spirit bears have much to teach us about larger questions of perseverance, self-sacrifice and ecology, McAllister argues. This stunning new book, a collection of extraordinary photographs and personal narrative, is the product of McAllister’s 25 years exploring, researching and campaigning for B.C.’s Great Bear Rainforest, the world’s largest remaining intact temperate coastal rainforest. It is an ode to the forest’s elusive wildlife—the bears, whose brows furrow like humans when they are concerned, the salmon, some of whom bear deep, red scars, “badges of honour,” trumpeting their escape from a whale or bear. It is a clarion call to care.

In introducing readers who might never visit the Great Bear Rainforest to a fierce, wild expanse of mist-shrouded fjords and towering cedars stretching from Vancouver Island to Alaska, McAllister hopes real action might be taken to ensure its survival.

So much is at stake. The forest’s fragile waters sit squarely in the shipping route of the proposed Northern Gateway pipeline, which would turn the surrounding jigsaw of islands into a supertanker expressway. And B.C.’s aggressive push into liquefied natural gas is set to fundamentally alter the forest’s ecology, says McAllister, who was introduced to activism at the blockades at Clayoquot Sound, as a 19-year-old.

These days, he lives in the tiny, coastal community of Denny Island, with his wife Karen, with whom he founded the wildlife conservation society Pacific Wild. Their children, aged eight and 11, attend Denny’s one-room school. The family travels by boat—there are no roads. People are few and far between. But in the Great Bear Rainforest, one of the planet’s richest and most spectacular ecosystems, McAllister writes, “there is simply life everywhere.”