Mohsin Hamid, a writer without borders

Book review: Mohsin Hamid’s book of essays works to reconcile the liberation of globalization with feelings of rootlessness

Share

DISCONTENT AND ITS CIVILIZATIONS

Mohsin Hamid

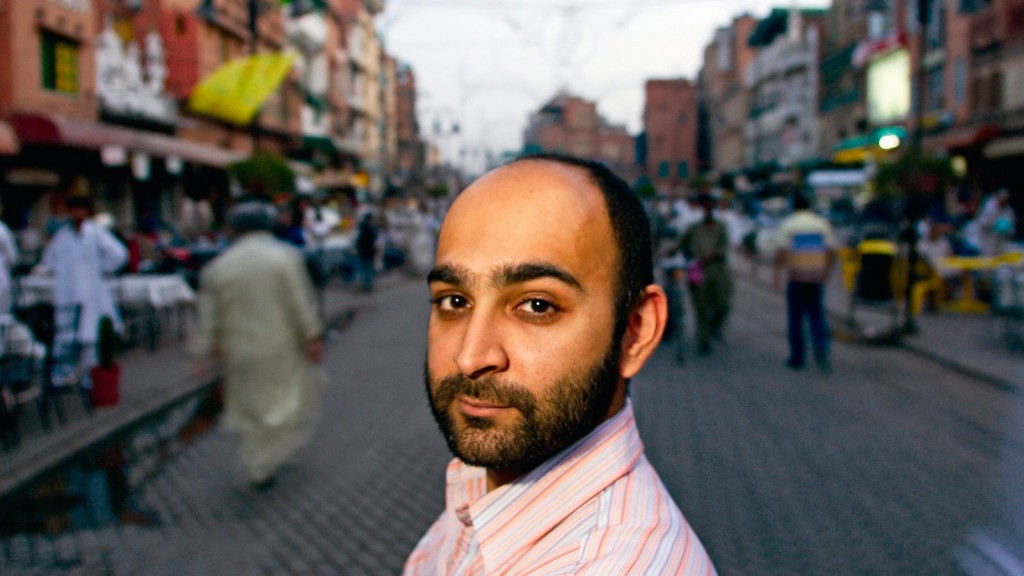

Mohsin Hamid was born in Pakistan, raised in the United States, lived in London for eight years—acquiring British citizenship while there—and currently resides back in Lahore. His travels exemplify either the liberation afforded by globalization or the rootlessness it has borne. Discontents and its Civilizations, Hamid’s first non-fiction collection following three novels, bills itself as an argument for the more hopeful option. Hybrids like himself, he writes, “reveal the boundaries between groups to be false.” They also, ideally, might help bring groups together.

That central insight and aspiration gains most urgency in Hamid’s articles about Pakistan, which, in the aftermath of 9/11, increasingly reflect Hamid’s divided self. Hamid left New York for London shortly before the attacks, and he writes about the great strain it placed “on the hyphen bridging that identity called Muslim-American.”

That strain informs his best essays, in which he tries to demystify Pakistan for Westerners who regard the country as a hotbed of extremism, and don’t recognize the terrorism that resulted from the war in Afghanistan (“America’s 9/11 has given way to Pakistan’s 24/7/365” Hamid memorably writes) or appreciate the fear elicited by ever-circling drones.

These arguments are always accompanied by their opposites: moments when Hamid casts a critical eye inward, denouncing his country’s “celebration of the militant.” And it’s by working to find his footing between these two poles of identity, neither of which fit him neatly, that Hamid offers the most passionate and eloquent expression of his mistrust of monolithic categories and his extolment of individuality and self-creation.

Unfortunately, not all of Discontents hits such highs. A number of its pieces, born as op-eds or short personal essays, suffer from restrictive word limits or lost currency. Grouped into a collection, too many of them float by, their resonance ephemeral, only barely held together by the unifying idea of Hamid’s hybridity. The more Hamid is able to stretch out, the more discerning he becomes, but one gets the sense that he largely saves such heavy lifting for his novels. It’s a shame, because there’s much to learn from Hamid’s personal experience, which so vividly captures the divisions we’re struggling to break through today.