‘A crash course in manhood,’ caught on film

With Hollywood-ish rebels and posing soldiers, a new doc about an American-turned-captured-rebel is also about filmmaking itself

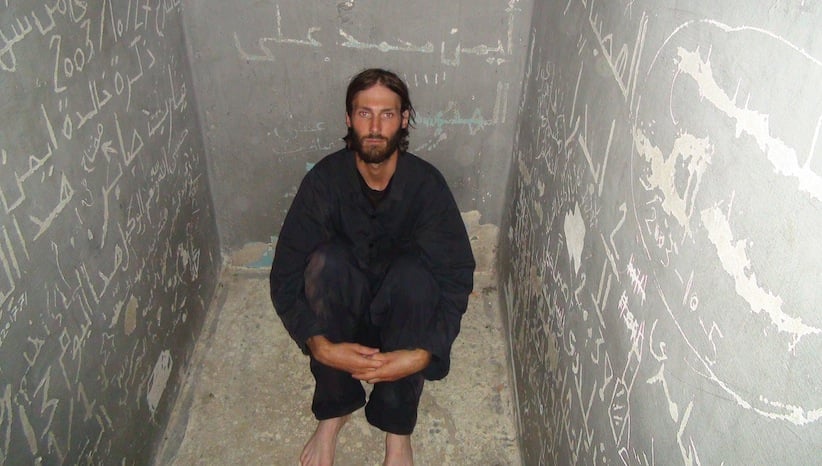

Screen capture/’Point and Shoot’

Share

On its own, it’s a riveting tale: the story of a mild-mannered, deeply sheltered 20-something, raised in comfortable middle-class America, who is shaken from his comfort and, inspired by the glamorously filmed safaris of adventurer Alby Mangels, sets out on his own kind of safari by travelling to the Middle East, alone and shooting video of wheelies in the desert; while he’s there, he gets into adventures, is attacked by a mob, buys a sawed-off shotgun, embeds himself with U.S. troops in Iraq, and freelances, without training, for the Baltimore Examiner.

And that’s just the beginning of the story of Matthew VanDyke and his pursuit of a “crash course in manhood.” If you’d followed along closely with the news in 2011, you’d know this part of the story of the photographer-turned-activist: while there, he went to Libya in the throes of the Arab Spring, deciding he didn’t just want to film his own coming of age but to participate as a rebel fighter in Libya’s youthful struggle. Not long after joining the rebel forces he would be captured and placed in solitary confinement for nearly six months; after he was freed, and against the wishes of his family and advisors, he returned to Libya to finish the job he had begun. Once Moammar Gadhafi was overthrown and then killed, VanDyke came home, certainly now the man he had intended on becoming. But soon after, he returned to the Middle East, to support those taking up arms in the Syrian revolution. Forget about mere manhood: VanDyke was now a freedom fighter.

“From the first day that he came to me, the way he talked about going on an intentional journey to create himself, to make himself into a man–I just thought ‘wow,’ ” said Marshall Curry, the 44-year-old director of Point and Shoot, which enjoys its Canadian premiere at Toronto’s Hot Docs festival this week, and was freshly named the best documentary at the Tribeca film festival last week. “A lot of the time we think of people going on a journey going to adulthood, it’s rarely as conscious a decision as this appeared to be.”

If Point and Shoot was just that narrative, told straight-ahead, it would be an interesting enough film. Curry, who has been twice nominated for an Oscar–once in 2006 for Street Fight, and again in 2011 for If A Tree Falls–certainly knows a good yarn when he hears one. Better yet, VanDyke’s story came complete with his own footage, nearly 200 hours’ worth. But what sets that documentary apart–and what gets Curry excited–is its meta quality: that it doubles as an exploration of filmmaking itself.

“Almost every scene in the whole thing has something to do with filmmaking,” said Curry. There’s the way VanDyke uses the camera to capture his fears; there’s the moments where American soldiers ask VanDyke to film them “looking like soldiers,” even though that’s what they were; there’s the latter third of the film, which looks at how the Libyan war was one waged with footage and the aid of the Internet. And there are the practical and moral quandaries of being someone with a gun in one hand and the camera in the other–indeed, an appropriate analogue to documentary-making.

“As a filmmaker, I have that struggle often when I’m making a film, where I’m talking to somebody who I maybe care a lot about, and they’re in a difficult moment and I’m having to be both present with them as a human being who has feelings and cares, and also think about focus and light and framing of the shot. And I find that very difficult, to do both those things at the same time,” said Curry.

But the question of image also raises concerns about authenticity and image control–especially in the fraught realm of documentary filmmaking, a medium so ripe for myth-building, with a character at its core who was criticized for being too cavalier with his privilege, for being foolhardy on a quixotic stunt of a quest. Some argued at the time that his approach was irresponsible and may endanger reporters. He came with his own footage, and perhaps an agenda of his own when it came to his narrative. He shopped his story around to multiple filmmakers, finally settling on Curry (who said he didn’t know exactly why was chosen over the others). One comes away from the film with a deep empathy for Van Dyke and his mission—which might in itself ring alarm bells.

None of this worries Curry. “Day one, I said the only way I would consider working on this film is if I had 100 per cent creative control. And he was fine with that,” he said, adding that there were hours of interviews and many more hours of editing that were just as important as the footage from the field. “I think the facts themselves are not disputable…these things did happen to him. The question is just interpretation. I thought by showing his footage and by listening to him talk and reflect and struggle with these questions that an audience could wrestle with these questions themselves.”

The back end of the film deals with it head-on. While capturing a Gadhafi-loyalist’s manse, VanDyke’s rebel allies ask him to make sure they get a nice shot of them, leading to his frustration about what role he plays there; there is a collage of shots of VanDyke recording then rerecording himself from a better angle, resetting the frame, getting the shot to read as he wants it to. By focusing the lens, Curry turns Point and Shoot from merely a gripping, taut bildungsroman into a smart treatise on the preening fabrications of society today– Instagram and Snapchat turning us all into photographers and filmmakers, telling stories about ourselves as we see ourselves living them. VanDyke was someone with a job–albeit the unusual one he gave himself, of freeing Libya from tyranny–who told his own story in the way that we all do.

“I just love that: the way we’re so interested in the way we’re captured and portrayed in film, and that the way the films feed back to make us different,” said Curry. He was struck, he remembers, by the fact that Libyan rebels repeatedly asked VanDyke to film them in the heat of battle, toting guns and firing ballistics–inspired as they were by Hollywood action films. “I had thought that obsession would be an American thing. And then to see guys that–at the same time they are fighting the most high-minded, important battle that anyone can imagine, of freeing their country from a brutal dictator–at the same time, they want a picture of themselves with a big gun so their girlfriend can see them. I love that.”