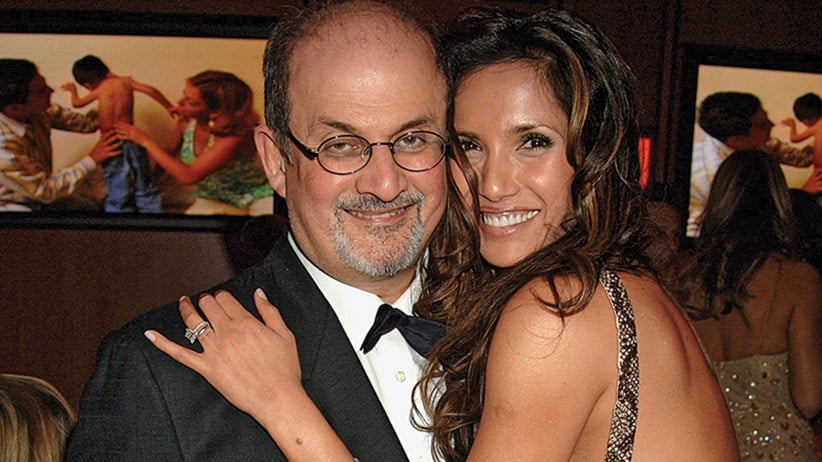

Padma Lakshmi: Rushdie, racism & the ‘girl thing’ no one mentions

Padma Lakshmi, the ‘Top Chef’-judging, billionaire-dating former model, has written the über female celebrity memoir—frank, juicy and surprisingly radical

Padma Lakshmi in New York. (Trunk Archive)

Share

Padma Lakshmi’s new memoir, Love, Loss and What We Ate, begins with a scene that cleverly combines her dual claims to celebrity: her marriage to celebrated novelist Salman Rushdie—who left his third wife in 1999 for the Delhi-born model and actress 23 years his junior—and her culinary cred, fostered as a judge on Top Chef, the popular Bravo reality show. It’s summer of 2007, and her eight-year relationship with Rushdie has just ended. She’s living in what she calls the “Sorry Hotel,” “a musty residential place,” while suffering psychic and physical pain recovering from surgery. A bag of kumquats sent by her mother in Los Angeles topples to the floor, a perfect symbol of her life at this moment. Overwhelmed, Lakshmi rallies to transform the fruit into kumquat chutney (recipe provided).

A triumphant “When life gives you kumquats, make kumquat chutney” spirit pervades this evocatively written book, a female uber-memoir that packs a dizzying array of modern lady themes into its 324 pages. The tale, spanning continents, includes cultural dislocation, illness, racism, sexual assault, love, heartbreak, marriage, death, divorce, single motherhood, custody battles, weight battles, a “Lean-in” class in brand-building. And: recipes!

She didn’t set out to write a full memoir, Lakshmi says by phone from her New York City apartment. Her contract was for a healthy-eating book with personal stories illustrating her philosophy about food, a topic “entwined in everything that I touch,” she says. “I come from a family that thinks about what we’re going to make for dinner when we’re clearing plates from lunch.”

As she began writing, a more complex story emerged: “Rather than write about healthy eating, I wrote about what really feeds me.” The result, she says, is “a clear feminist manifesto.”

Coming from a woman known for model looks and high-profile male companions, that label may surprise some. But Lakshmi has produced an unusually nuanced book that breaks new ground discussing “girl things,” to quote British tennis player Heather Watson in talking about how her period contributed to a lacklustre Wimbledon performance. Beyoncé similarly brought miscarriage out of the shadows with her song Heartbeat. Lakshmi not only tackles a grab-bag of still-taboo “girl things” (messy periods, undiagnosed endometriosis, female sexual agency), hers is a modern Horatia Alger story of unapologetic, strategic female ambition and voracious appetites. So “feminist manifesto” isn’t that far off.

It could be a novel. Her father abandoned the family when she was one. Her mother, a nurse, emigrated to the U.S. when Padma was two; Padma joined her two years later. At age seven, she was sexually assaulted by a relative of her new stepfather. When she reported it, she was sent to India until her mother divorced.

As a teenager in L.A. she was filled with “brown girl’s self-loathing,” triggered in part by classmates’ racist taunts and bullying; ashamed of her name, she became “Angie” for a year. Modelling in Europe, she wished she was a more “saleable colour,” she writes. She’d learn a lesson in acceptance from photographer Helmut Newton, who saw beauty in an 18-cm scar down an arm from a car accident: “Because this great photographer thought it was okay, everyone treated me differently,” she says. “But the scar was the scar it always was.”

Lakshmi was 28, suffering from a “crisis of self-worth,” when she met Rushdie —“our own Hemingway”—at a glittery party thrown in “the shadow of the Statue of Liberty.” (Were this fiction, the detail would be deemed implausible.) Her modelling career was winding down; she’d published her first book, Easy Exotic: A Model’s Low-fat Recipes from Around the World (“Everyone wants to know what a model eats,” she writes). Rushdie was a glamorous figure, newly freed from a decade-long fatwa on his head. His words, over the phone and on the page, seduced her: “I could not resist him.”

Rushdie is dispensed with quickly in the memoir. “Only two chapters deal with that relationship, 15 are about everything else,” she says. Lakshmi shares how she’d prep elaborate curries for parties attended by Susan Sontag and Don DeLillo. Ultimately, the couple grew apart: “What’s flattering in the first year can be suffocating in the eighth,” she writes. Her endometriosis, a gynecological condition only diagnosed months before the marriage’s end, created a fault line; Lakshmi writes of excessive bleeding and pain during and between her periods that led to a lack of interest in sex. Rushdie was “absent emotionally and often physically” while she was ailing, she writes.

Her version provides a counterpoint to Rushdie’s 2012 book Joseph Anton: A Memoir, written in the third person, which describes his ex as erotically beguiling but opportunistic and possessed of “majestic narcissism.” She’s “an American of Indian origin who had grand ambitions and secret plans that had nothing to do with the fulfillment of his deepest needs.” Lakshmi says she hasn’t read the book but laughs when told it refers to her “frequent moodiness.” “If you read my memoir, ‘moodiness’ as a descriptor of how I was feeling is quite the euphemism.”

Lakshmi’s book doesn’t just provide a counternarrative to a story told by a great storyteller, one that takes its own creative licence (the “Sorry Hotel” is in fact the far-from-derelict Surrey Hotel, where chef Daniel Boulud personally sent up Lakshmi room service from his downstair’s restaurant). It also outs the grim realities of endometriosis—a quest in which she’s joined by Lena Dunham, who has also gone public about suffering from the condition. Lakshmi co-founded the Endometriosis Foundation of America, focused on a condition 10 percent of women endure, to destigmatize the condition, she says. “The reason endometriosis is unknown and why so many women suffer in silence and agony is because we’re not supposed to talk about our periods. Our period is supposed to be icky. We have several commercials a night for erectile dysfunction. So why can’t we talk about something that occurs every month to half the population?”

She is equally frank about her sexuality, still a radical stance for a woman in the public eye. She was “promiscuous” while living in Europe, she writes, again unapologetically: “Some I regret, but not all.” She does regret the cavalier way she juggled billionaire Teddy Forstmann, more than 30 years her senior (with whom she took up as she was exanding her brand into spices, teas, home decor and frozen foods), and venture capitalist Adam Dell. This played out in the tabloids, and then the courts, when Lakshmi unexpectedly, but joyously, became pregnant at age 39. Forstmann wanted to raise the child as his; she insisted on a DNA test. Dell, the father, launched a bitter, public battle for co-custody, which was settled out of court. She reports the two have made peace.

Still, she bristles at the double standard: “Beyond my own self-absorption, and my total lack of concern for whether I was hurting either Teddy or Adam, my feminist and wilful side kicked in. Why couldn’t I date more than one man? Men do it all the time without compunction.”

Lakshmi addresses head-on her “gold-digger” label, quoting the New York Times describing her as “a semi-celebrated hustler.” Writing the memoir brought clarity to her pattern of older, wealthy partners, she says—the boyfriend in Italy who introduced her to the arts and fashion; Rushdie, who exposed her to the literati; Forstmann, who ferried her around in private jets before his 2011 death. “It’s easy to say, ‘She has daddy issues,’ ” Lakshmi says. But this isn’t about seeking father figures, she argues: “The best way to be included in a club is to learn from the members who already belong. And nothing in my upbringing gave me exposure to the things I wanted to do in my life. I always felt like I was on the outside looking in, a common experience of immigrants.”

She points to other double standards: “Whenever I go on a press tour for Top Chef,” she says, “nobody asks [fellow judge] Tom Colicchio how he keeps his figure.” She knows her fame hinges on her “genetics,” and wanted the book to address “the superficial artifice that goes into what we feed the general public.” Of the question, “How does she stay thin?” she says: “I gain three sizes in the six weeks I film Top Chef, but you don’t notice because I have three full-time people whose job it is to make you not notice.”

In a bookend to the kumquats moment, Lakshmi, who explores food in its many profound iterations—from dining at Copenhagen’s celebrated Noma to cooking for a dying loved one—tackles the most primal female cuisine: “The decision to consume my placenta was not an easy one,” she writes at one point. Having staff to boil the afterbirth down to powder and fill capsules no doubt made it easier. No recipe is provided, but the moment seems a perfect blend of luck, achieved privilege, and a sometimes disquieting brand of feminism, not unlike Lakshmi’s story itself.

Correction: The story has been amended to reflect that Lakshmi did not lose her custody battle; it was settled out of court.