Putting Trudeaumania under a microscope

A historian tackles the topic of Trudeaumania in this new biography

Share

He haunts the bookstore shelves still: biographies and studies of Pierre Trudeau keep on coming.

No Canadian prime minister, not even John A. Macdonald, has generated so many volumes. There are few aspects of Trudeau’s life and work that have not been chronicled, probed, interpreted and reinterpreted.

Now Robert Wright, a historian, dissects and attempts to dispel the myth of Trudeaumania, which is claimed to have propelled Trudeau’s political career and solidified his election as Lester Pearson’s successor as prime minister in 1968.

Wright offers a fascinating and well-constructed narrative, tracing how a brilliant but somewhat aloof Quebec intellectual, one who could easily have spent his life churning out highbrow think pieces on French-Canadian nationalism and federalism, morphed into arguably the most charismatic and brilliant figure to hold Canada’s highest elected office.

Still, though the author puts Trudeau’s rise to power during the ’60s under a microscope, using insights gleaned from Trudeau’s papers and an extensive examination of press and television commentary of the period, his version of this well-covered story is not as revisionist as he asserts it is.

Related: Being Sacha Trudeau

Trudeaumania has long been seen by the likes of Stephen Clarkson and Christina McCall, and more recently by John English in his two-volume biography, as an exaggerated phenomenon and hardly the main reason for Trudeau’s ascension. True, as Wright argues, too much has been made of the connection between the euphoria of Canada’s Centennial and Trudeau’s popularity, or that Trudeau tricked his way to the top to “serve his own ambitions.”

Wright also asserts that Trudeau was not as polished a performer on TV as is believed and that his political success was not contingent upon his “deft handling of the new medium.”

Yet throughout the book he provides one example after the other of the future PM adapting and eventually becoming skilled, if not a star. Trudeau later famously disdained the media, yet journalists, especially Peter C.Newman, who can rightly claim to have discovered Trudeau, understood that he was a unique and fresh personality.

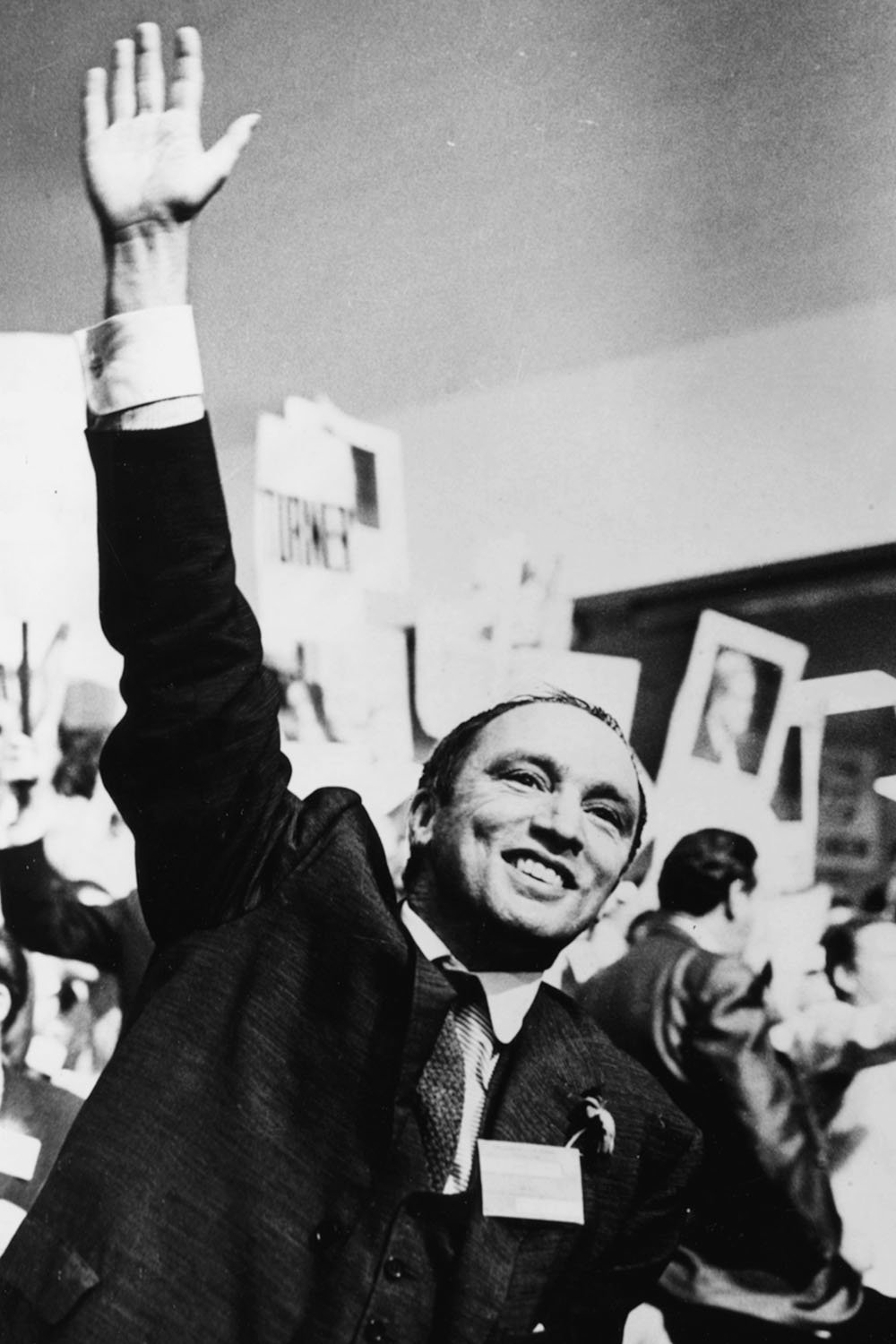

Trudeau may not have been Canada’s JFK or, at age 48 in 1968, the fifth Beatle. The exuberant young women who chased him during his first election campaign as leader were not the reason he won. That he was backed by group of English-speaking academics and was probably too much of an egghead, albeit a cool one, for a lot of politicians and members of the media, however, does not diminish his impact on Canadian history or on that captivating period in Ottawa when everything changed.