A light goes on for General Electric

GE’s credit cards are gone; so are the microwaves. How one of America’s biggest corporations is trying to return to its industrial roots.

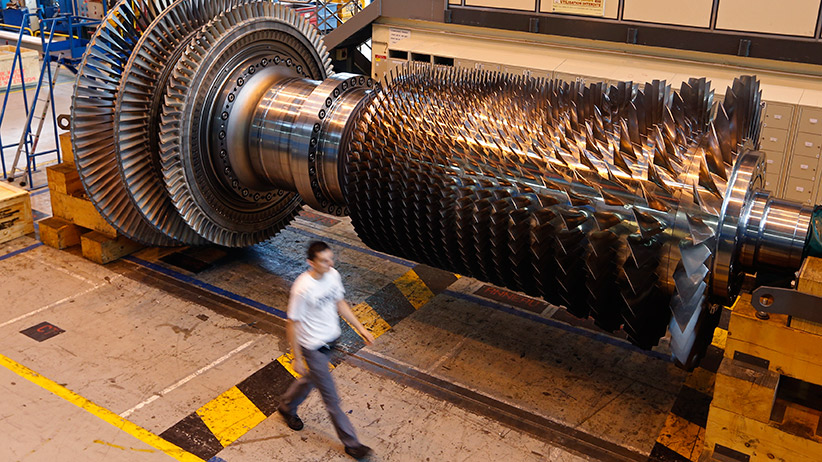

A worker walks past a gas turbine under construction at the gas turbines production unit of the General Electric plant in Belfort, June 24, 2014. France won an option to buy 20 percent of Alstom from conglomerate Bouygues on Sunday, in an eleventh-hour deal clearing the way for the agreed sale of most of Alstom’s energy business to GE. REUTERS/Vincent Kessler (FRANCE – Tags: BUSINESS ENERGY BUSINESS EMPLOYMENT) – RTR3VGMR

Share

In the popular TV sitcom 30 Rock, Alec Baldwin played Jack Donaghy, an ambitious NBC executive, whose rise up the ranks of parent company General Electric landed him the hilariously awkward corporate title of vice-president of East Coast television and microwave oven programming. It’s a send-up of GE, which, until recently, owned the network—the real-life NBC—that aired 30 Rock, and makes everything from boiling-water nuclear reactors to four-square Belgian waffle-makers.

The scattered approach is gradually becoming a thing of the past. While GE is still a monster—it generated US$146 billion in global sales last year—CEO Jeffrey Immelt is in the process of refocusing GE on key infrastructure businesses like water, power generation, aviation, rail, health care and oil and gas. To get there, Immelt has steered GE away from its heavy reliance on financial services through a flurry of deals. GE sold off the rest of NBCUniversal in 2013 for US$16.7 billion, bought the energy assets of French engineering giant Alstom earlier this year for $17 billion, and this week struck an agreement to sell GE’s appliance and housewares division to Sweden’s Electrolux for US$3.3 billion.

The changes at GE, one of America’s biggest and oldest corporations, reflect growing unease at how the pre-recession economy had come to rely heavily on financial engineering for growth, as opposed to actually making things. “It became clear in the early part of this century, and the global financial crisis put the exclamation point on it, that [financial services] wasn’t going to be the way of the future,” says John Rice, president and CEO of GE’s global growth and operations. He adds that the decision to double down on industrials was also spurred by studies suggesting the world needs to invest US$4 trillion annually in things like power plants and water treatment facilities, but was falling short by about US$1 trillion every year.

It’s not just GE’s portfolio of assets that’s being overhauled. There are also efforts to change the very way GE does business. Like many other firms, it’s keen to adopt the fast-moving and innovative approach of Silicon Valley success stories like Google. But cutting through the bureaucracy isn’t easy. Turning around a ship the size of GE—305,000 employees in 170 countries—takes time. All of which explains why the stock, now trading around US$26, has been slow to recover since the financial crisis and continues to trade below the $40 it was at when Immelt took over from Jack Welch in 2001.

For most, the proposed sale of GE’s appliance division represents the most noticeable change. The century-old business introduced Americans to such time-saving devices as the electric toaster, electric range and clothes washer, making GE a household name. But GE was at risk of falling behind fast-growing global competitors in the appliance market, such as Samsung. It’s also a rather small piece of the overall company, accounting for less than three per cent of earnings in 2013.

Of more interest to investors, however, are GE’s efforts to reduce its reliance on financial services for profits. At its height, GE Capital was responsible for nearly half of the company’s earnings, making GE the largest financial provider in the U.S. that wasn’t a bank. Richard Powers, a lecturer at the University of Toronto’s Rotman School of Management, says the finance business was often lauded for its ability to mask the cyclical weaknesses in GE’s other divisions: “It threw off cash and covered off losses.”

That is, until the credit crisis hit. Suddenly, all those credit cards, auto loans and risky subprime mortgages were burning a hole through GE’s balance sheet. In response, the 130-year-old American icon cut its dividend, halted a share buyback program and took a US$3-billion emergency loan from Warren Buffett. GE has since sold off the subprime business (taking a US$1 billion haircut in the process) and earlier this summer raised US$2.9 billion by spinning off its consumer finance arm, Synchrony Financial, the largest provider of store-branded credit cards in the U.S.

The net result is that GE Capital is on track to deliver a more modest—relatively speaking—one-third of GE’s profits. Moreover, Rice says it’s mostly focused on commercial lending in areas where GE sells equipment, making the businesses more complementary. At the same time, Immelt’s biggest takeover deal to date, the purchase of Alstom, helped cement GE’s status as an infrastructure play among investors. Combining the two companies has made GE a pre-eminent player in the growing market for gas turbines, which are favoured by utility companies due to cheap gas prices and growing concerns about emissions (gas burns cleaner than coal).

Analysts say GE’s biggest growth opportunities lie in countries like China, with its huge appetite for infrastructure. However, GE is also trying to convince Wall Street its technological know-how can make companies in the developed world more efficient. GE calls it the “industrial Internet”—a catch-all phrase for real-time monitoring of things like wind turbines and jet engines, and then crunching that data to help operators use them to their fullest potential—and claims the two-dozen-or-so products it has launched in the space are on track to generate US$1 billion in sales this year. During a recent visit to Calgary, Immelt also suggested GE’s technology could help oil sands firms cut emissions, making further development more politically palatable. “They’re doing great today, but they’re not stopping,” says GE Canada chief executive Elyse Allan of oil sands firms. “They’re saying, ‘Help us find the next generation [of technology].’ ”

The new, more industrial focus seems to be working—at least so far. In its most recent quarter, GE reported a three per cent increase in sales to US$36 billion and a 13 per cent jump in net income to US$3.5 billion, with GE’s industrial businesses leading the way. There are risks, however. Selling big-ticket industrial equipment and the software to run it is a more predictable business—multi-year contracts, fewer competitors, no fickle consumers—but it’s also more capital-intensive. Products take years to design and build and require billions in research and development cash. The costs of a miscalculation are potentially huge. For all the talk about a manufacturing renaissance in the U.S., which has added more than half a million manufacturing jobs since 2011, it’s telling that GE is unwilling to exit the comparatively easy money found in the finance business entirely. Rice stresses that GE’s $325-billion portfolio of financial services assets “is very competitive and very attractive for investors, but needs to be part of a total company that’s generating more industrial earnings. That’s the mission we’re on.”

GE’s solution to making industrial equipment sales more dynamic is a company-wide program called FastWorks, based on the lean start-up movement championed by Silicon Valley entrepreneur Eric Ries. The idea is to let customers guide the development process by getting new products out the door quickly and fixing problems on the fly—not unlike how Apple fixes problems with its iPhone with ongoing software updates. By all accounts, Immelt has embraced the concept with the same zeal that his predecessor once showed for Six Sigma, the process-oriented manufacturing program that aims to remove defects in products. An example of how FastWorks had changed GE’s soon-to-be sold appliance division was recently described in the Harvard Business Review. A team of designers and engineers who set out to develop a new French-door refrigerator worked closely with sales staff, trying to incorporate their ideas and suggestions—no matter how silly. Then the fridge was put before customers, who had their own complaints. All were fixed in later design iterations. “What FastWorks forces us to do is develop a product quickly—a gas turbine, a wind turbine or a piece of health care equipment—that is designed for the market,” says Rice. “The focus is not to be perfect, but be iterative. If you’re going to fail, fail quickly, then come back and iterate again.”

The question is: Can GE’s hundreds of thousands of employees think like a bunch of coffee-fuelled whiz kids running a start-up in the garage? Powers calls it a “quantum shift” for a company GE’s size. While he credits GE for being well-run, he wonders why Immelt has embarked on such seismic changes after more than a decade at the helm. Rice, however, says GE is just changing with the times: “You have to respond to markets and customers. The ones that don’t pay attention end up in the wrong place. We’re not going to be one of those companies.”

GE may have once benefited from all those 30 Rock jokes when it was in the TV business. But, apparently, the suits in the corner office weren’t laughing along with the rest of us.