When paying the boss to leave pays off

Call it the Frank Stronach factor

Hans Punz/AP

Share

Among the rites of passage for business journalists in Toronto, for the longest time, was a trip to the annual general meeting of Magna International, the auto parts giant, to scrum with the company’s mercurial CEO and founder, Frank Stronach. The following exchange would invariably unfold:

Reporter in rumpled suit: “Why should you get 500 votes for every share you own?”

Stronach: “The shareholders voted for it.”

Reporter: “But why do you deserve $60 million in pay?”

Stronach: “I should get more.”

It went like that every year, followed by outraged headlines about Stronach’s jackpot compensation deals, and much desk-pounding from Magna’s long-suffering shareholders that something, something, must be done.

The other day, Magna released its latest disclosure filing ahead of the annual meeting on May 8. Stronach got a massive paycheque, again in 2013, this time, $52 million in consulting fees and bonuses. But the indignation was strangely absent. I say strangely, because Stronach doesn’t even work for Magna anymore. He’s been in Austria building Team Stronach, his upstart political party. So let’s see, Stronach collects a sum 722 times greater than the median household income—an amount more than the entire senior executive team at Magna took home—and his contribution was so meagre, Magna mentioned him just five times in its latest annual report. Shouldn’t somebody be throwing chairs?

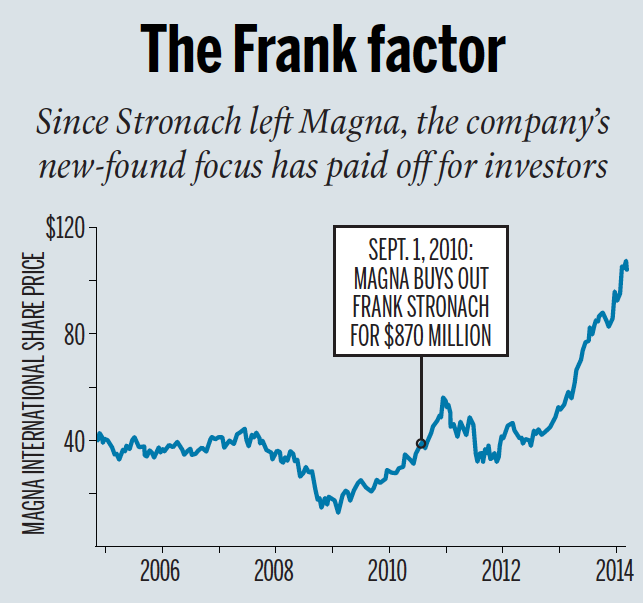

If shareholders are keeping quiet, it’s probably because they’re too busy tallying up their returns from Magna’s shares, post-Stronach. Since paying him a staggering $870 million to go away in 2010, in a deal that became a flashpoint for shareholder activists at Canada’s biggest pension funds, Magna’s value has exploded. You used to hear analysts grumble about the “Frank factor” weighing on Magna, but no one could really put a price on it. Now we can. Magna’s market capitalization (the value of all the company’s outstanding shares) had been stuck at below $9 billion since the 1990s. Today, it’s $25 billion. Magna’s share price has more than tripled since Stronach left the building. It’s no doubt a reflection of the company’s laser-like focus on its core auto parts business—which has driven sales and profits to new heights—and away from Stronach’s former grand diversions, be they horse-racing, theme parks or, at one point, even launching an airline. But Magna has also done things to reward its shareholders, such as boost the dividend and buy back shares—things it didn’t bother to do when their votes didn’t matter.

It’s instructive to recall the extent to which tempers flared on Bay Street after Magna said it would pay Stronach so much to give up control of the company’s multiple voting shares. A group of pension funds, firmly on the side of angels, as far as most uninvested onlookers were concerned, opposed the terms of the deal, calling it “monstrous.” They took their case to the Ontario Securities Commission and lost. They appealed to the courts, and lost again. The Ontario Teachers Pension Plan Investment Board even bought a single Magna share, just so it could oppose the deal.

I was all ready to write something snarky here about Teachers wishing it had bought more shares, but a review of its holdings compiled by Bloomberg shows it did, about 750,000 of them. Still, that’s a pittance of a position in one of Canada’s biggest and best-performing stocks. In their anger and frustration over Stronach’s treatment of minority shareholders, there’s a lot to suggest that his critics, invoking shareholder rights, let those emotions get in the way of what turned out to be the right decision for shareholders. Because, as egregious as that deal with Stronach was, it was one that 75 per cent of Magna’s minority investors voted to approve. And, in hindsight, it was the smart move.

The buyout in 2010 didn’t entirely untangle Stronach’s tentacled grip. Each year since, Magna has continued to pay consulting fees and performance bonuses to Stronach in accordance with the deal. But under the agreement, 2014 is the last year Stronach will get a penny in pay from Magna. The company literally underlined that point in its proxy circular: “The Stronach compensation arrangements will not be renewed, extended or replaced with any other form of compensation.” It will be an end of an era. But Magna’s shareholders have already moved on.