Why Canadians are wary of self-driving cars

The idea makes us feel anxious and powerless, survey suggests, but our kids are going to love them

New Autopilot features are demonstrated in a Tesla Model S during a Tesla event in Palo Alto, California October 14, 2015. REUTERS/Beck Diefenbach

Share

You had to be excited this month about autonomous cars and the promise of a driverless future—at least, if you were a politician. In Washington, the Obama administration announced plans to shower US$4 billion on the technology over the next decade. On New Year’s Day, Ontario officially fulfilled Kathleen Wynne’s promise to open its roads for autonomous car testing, while the mayor of Saskatoon last week called for infrastructure tailored for self-driving vehicles.

If you go by the timelines provided by believers, the pols are playing it smart. Most major carmakers have self-driving technology in development. Tesla’s latest models already boast a limited autopilot feature, and Google hopes to have an autonomous vehicle (AV) ready for market within four years.

But do consumers share that enthusiasm? What will it take to get North Americans—steeped in a century’s worth of culture equating the car with independence and self-realization—to give up the wheel?

These are big questions with big money riding on them (this I learned during a visit last summer to the Mountain View, Calif., idea factory where Google is developing and testing its AV technology). Impressive as self-driving prototypes are, it’s clear the engineers are proceeding on big assumptions about what the consumers will want, or accept.

So it was gratifying to see the first in-depth data on how Canadians feel about this idea, produced with little fanfare last week by GfK, a global consumer marketing research firm.

Canadian respondents, it turns out, are not exactly thrilled by the idea of the driverless car. More attractive to them is the idea of human-driven vehicles featuring automation that enhances safety, such as self-braking and automatic steering in emergencies, or automatic calling to emergency services in the event of an accident. Cars equipped with all of these features appealed to 42 per cent of respondents, while AVs appealed to just 26 per cent.

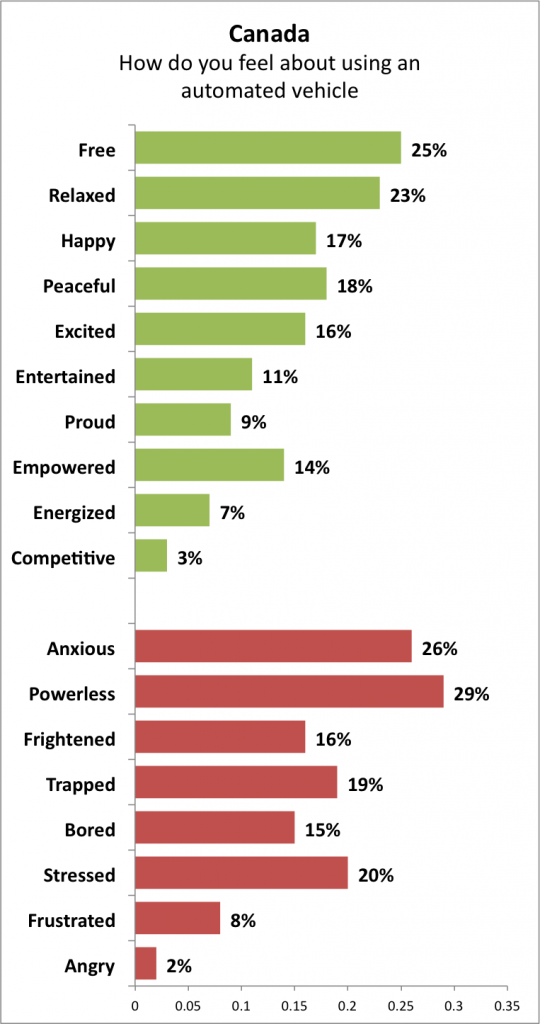

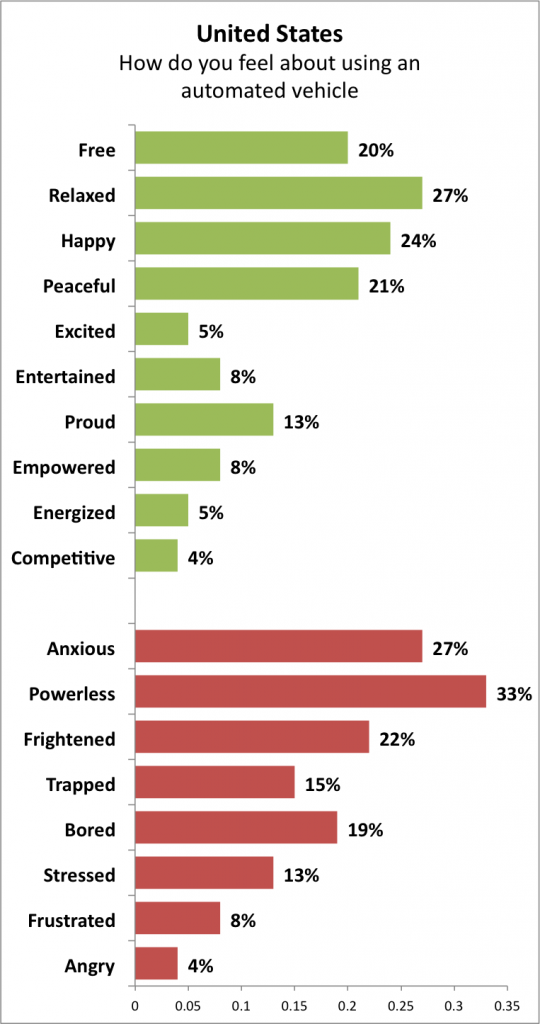

The surveyors gave respondents a list of 18 emotions to choose from to describe the notion of riding in autonomous cars, and the idea triggered as much alarm as reassurance: more than one in four chose “anxious,” while 29 per cent said it would make them feel “powerless.” That was slightly more than picked “relaxed” or “free” (respondents were allowed to choose more than one).

Canadians were marginally more receptive than Americans, who GfK has also canvassed: fully a third of U.S. respondents said autonomous cars induced feelings of powerlessness.

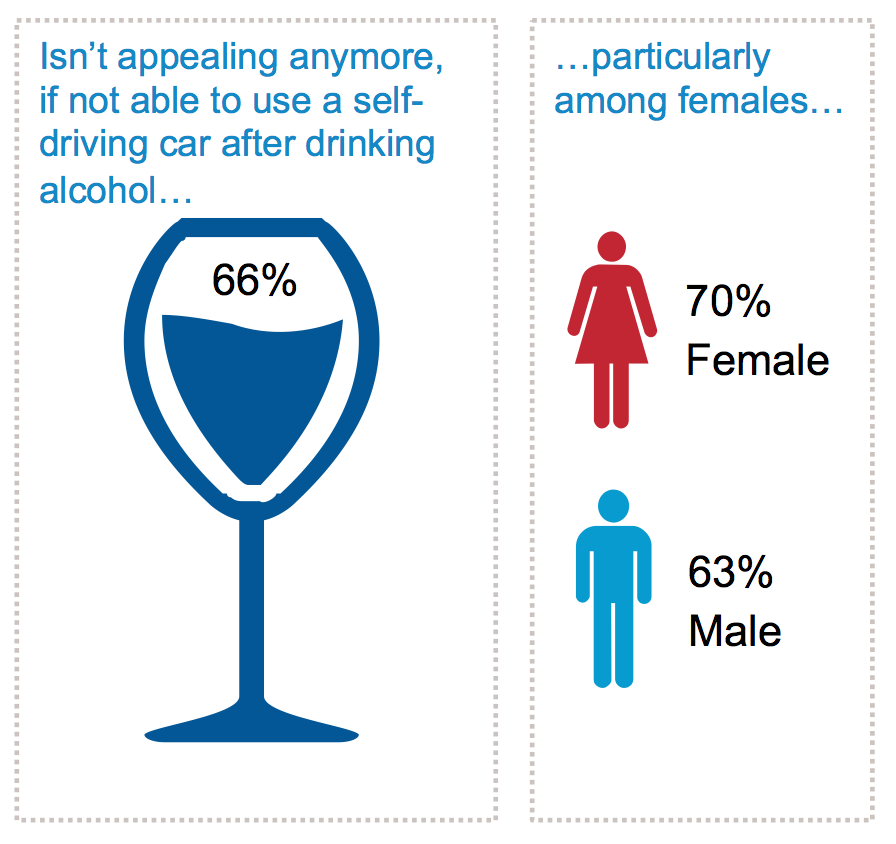

But if we’re to have self-driving cars, it seems we’ll demand a high level of reliability. Some 66 per cent of respondents—including 70 per cent of women—saw little point in AVs if you couldn’t ride in them after drinking booze.

It’s important to note these attitudes varied widely across certain demographics. Young, employed, tech-savvy people—defined by the survey as “leading-edge consumers”—were far more favourable toward self-driving cars, and to all sorts of automation. That leading-edge cohort is what political leaders and transportation planners have their eye on when they promote autonomous car technology, says Carl Kuhnke, managing director of the Saskatchewan Centre of Excellence for Transportation and Infrastructure.

Pointing to the declining share of young people obtaining driver’s licences, Kuhnke forsees a future generation more interested in getting from A to B safely than doing so with full control of the vehicle. In one recent survey of American twentysomethings, he notes, more than seven of 10 said that, if forced to choose, they’d rather have a smartphone than a car.

“This is why the automobile manufacturers, who are not dumb bunnies, are moving toward what they call Level 4 autonomous vehicles—that is, fully self-driving,” says Kuhnke. “If seven out of 10 would rather have their mobile phone than a car, then put them in something that’s not called a car, and let them play with their phones.”

Judging from current trends, carmakers plan to get there incrementally, adding autonomous features year by year, such as the front-end radar all 10 major manufacturers have agreed to make standard by 2018, which will cut down on rear-enders and highway pile-ups. The steering wheel, accelerator and brake may stay in place until they are little more than a comfort to older motorists.

“The average person thinks about the Jetsons, with a big plastic bubble closing on them and locking, and the car taking you whichever way it wants to go,” says Kuhnke. “Well, that’s never going to be the case.”