Why Tim Hortons feels it needs Burger King

Can two weaker companies merge to mask their problems?

A Tim Hortons restaurant is seen located next to a Burger King restaurant in Lower Sackville, N.S. on Monday, August 25, 2014. Burger King is in talks to buy Tim Hortons in hopes of creating a new, publicly traded company with its headquarters in Canada. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Andrew Vaughan

Share

In the late 1990s an urban legend made the rounds that Tim Hortons adds nicotine to its coffee to make it addictive. It doesn’t, of course. But one might wonder if Canada’s biggest restaurant chain has slipped some type of memory inhibitor into its brew, judging from the immediate reaction by Tim Hortons Nation on social media—not to mention the NDP’s hand-wringing industry critic Peggy Nash—to the news Burger King is in talks to buy the chain.

The horror, the travesty, the injustice—an American burger chain is buying our national treasure.

Again.

It’s been nearly 20 years since Wendy’s snapped up Tim Hortons in a bid to create an international fast-food giant. That didn’t work out so well for Wendy’s. It wasn’t that Tim Hortons had struggled, at least not in Canada. In fact, a decade after that deal was completed, Tim Hortons accounted for close to three-quarters of operating income for the combined company. By 2005 Wendy’s shareholders were demanding the company spin out Tim Hortons as a standalone public entity to unlock its value, which it did the following year.

Now here we are again, a Canadian icon on the verge of disappearing into the rapacious bowels of American capitalism. Only this time the narrative is far more confounding.

For starters, let’s consider Burger King’s motivation for buying Tim Hortons. It is not looking for synergies. Don’t expect to see Burger King roll out twinned stores, with one counter selling Whoppers, the other Timbits, as per Wendy’s strategy when it owned Tims. Instead, Burger King wants to avoid paying U.S. taxes. If the deal goes ahead (no agreement has been finalized) Burger King will achieve this through what’s known as a “tax inversion.” It would buy Tim Hortons, then declare the newly merged company to be Canadian. And because companies in Canada enjoy a lower corporate tax rate than those in America—15 per cent in Canada compared to an official U.S. rate of 35 per cent—Burger King’s future tax bills could be a lot smaller.

Canada, it would seem, is the new Delaware.

So Burger King is buying Tim Hortons, but in doing so, the combined Tim Hortons and Burger King will be financially engineered to be Canadian, at least on paper. A statement released by the companies following the Wall Street Journal‘s initial report on the deal said Burger King’s largest shareholder, 3G Capital, a Brazilian private equity firm, would own the majority of the shares of the newly created company. And you can be sure any tax savings will flow back to shareholders in the form of higher dividends.

It’s clear what’s driving Burger King to pursue this deal. But there’s been far less attention paid to the question: what’s in this for Tim Hortons?

According to Tim Hortons, the answer—as it unceasingly has been for the past two decades—is the pursuit of international growth. In the statement from Tim Hortons and Burger King, the companies said the coffee chain will have “the potential to leverage Burger King’s worldwide footprint and experience in global development to accelerate Tim Hortons growth in international markets.”

Whether Burger King will have any more success delivering on that promise than Wendy’s did will be the question hanging over the new company. There is little question that in its current form, Tim Hortons has hit a wall. Its U.S. expansion has been an enduring disappointment. Every year has brought promises that the chain’s U.S. stores would finally deliver results to the company’s bottom line. The current vow, spelled out in Tim Hortons’ 2013 annual report, is that the chain’s U.S. stores will generate $50 million in operating income by 2018, a tiny sum considering how much the company has invested in its 859 U.S. stores. It really isn’t obvious how Burger King, which saw its annual sales tumble from $2.3 billion in 2011 to $1.1 billion last year, can catapult Tim Hortons to success in the U.S.

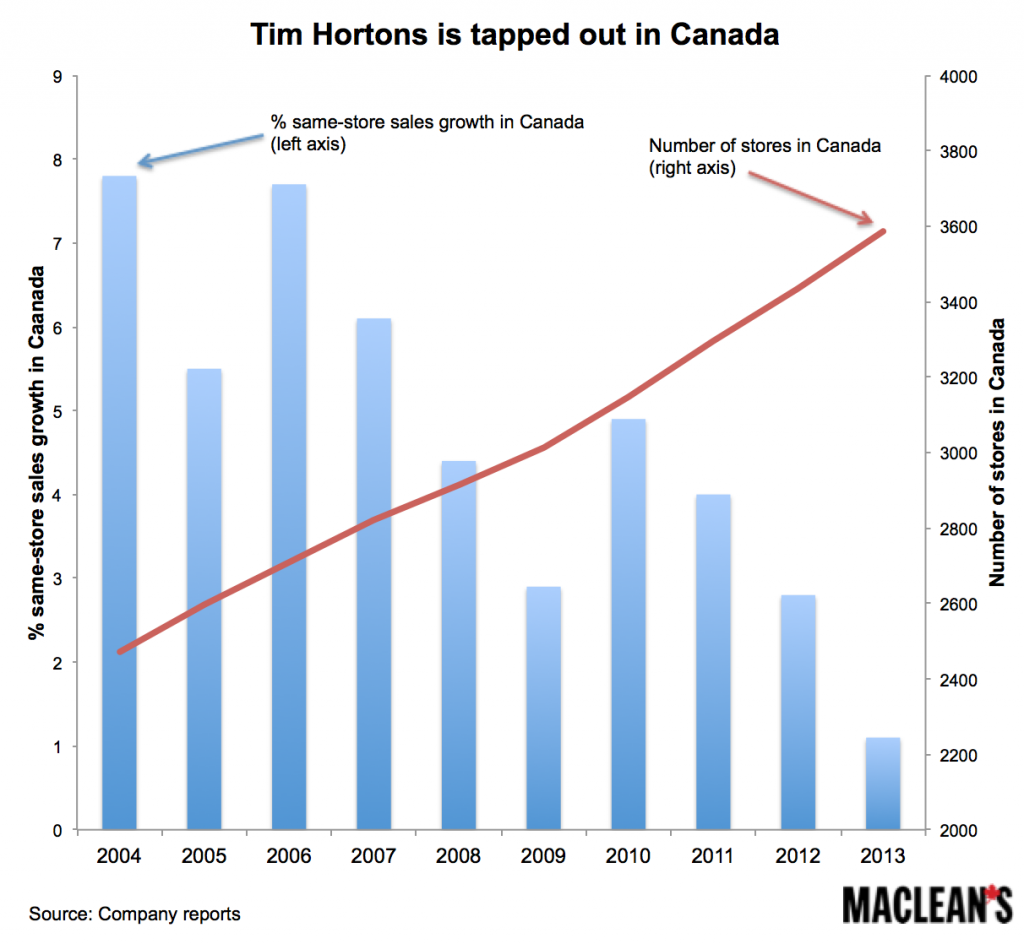

But Tim Hortons’ biggest challenge arguably isn’t its failed U.S. expansion. It’s that the market at home is tapped out. Were it not for opening scores of new stores every year, Tim Hortons growth in Canada would be paltry. Yes, the company’s CEO, Marc Caira, has promised growth from innovation and new products, but there’s an obvious limit to how much additional growth high-priced novelty donuts can deliver.

Can Burger King fix these problems? That’s debatable. But with its growth prospects limited as a stand-alone company, it wouldn’t be the first time two weak companies have joined forces to mask their shortcomings.