Alberta needs to be honest with itself about the budget

While opposition concerns around Alberta’s debt sustainability are misleading, the government’s claims around spending growth are equally so

Share

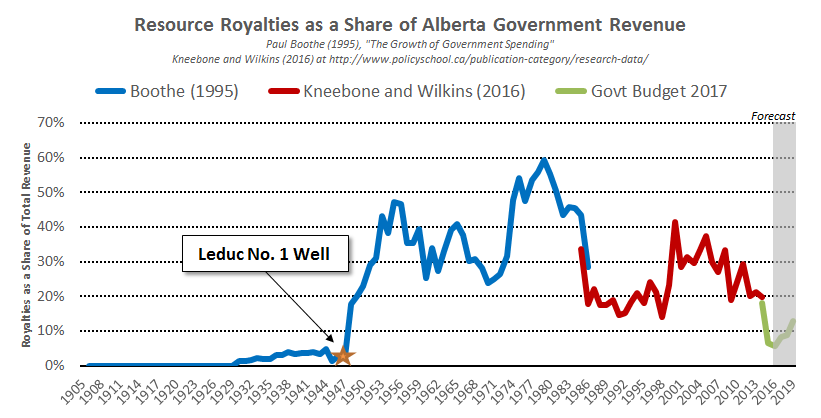

Alberta’s latest budget was a tough one. Oil prices remain low, and will likely stay low, meaning a key revenue source for the government is gone. Not since 1947 has resource revenue been a smaller share of revenue. There’s no easy way out of this hole.

The government has opted to act as a “shock absorber”, as it puts it, and will run deficits until resource revenues return. Neither new revenue sources nor spending restraint are on the table. Not surprisingly, this has sparked intense reaction.

Opposition parties see a “fiscal disaster” that will “take decades to fix.” The new PC Leader Jason Kenney tweeted the province is “drowning in debt.” My own initial reaction was one of surprise, disappointment, and a fair amount of confusion. (Yes, economists are people too.) Instead of pivoting towards a medium- or longer-run plan to get the province’s fiscal house in order, and move off our resource revenue dependency, we’ve remained on the same course the government set last year.

With a couple days to digest the new budget, and with the immediate reaction over, we can try to take stock of where we are and where we’re going.

READ MORE: Alberta marches forward, on boggy fiscal footing

I’ll focus on a couple narrow points. First, Alberta’s growing debt, whether advisable or not, is entirely sustainable. There’s no fiscal disaster here, not even close. But, second, the government is being less than honest about current and future spending levels. Spending is rising faster than the government claims, and is larger than it previously planned. Finally, there’s no clear path to balance. The government is betting (big) on future oil prices and meanwhile mischaracterizes the problem as a lack of economic diversification. (For more on government straw men, see this.)

Let’s start with the overall budget.

There’s a problem with this picture.

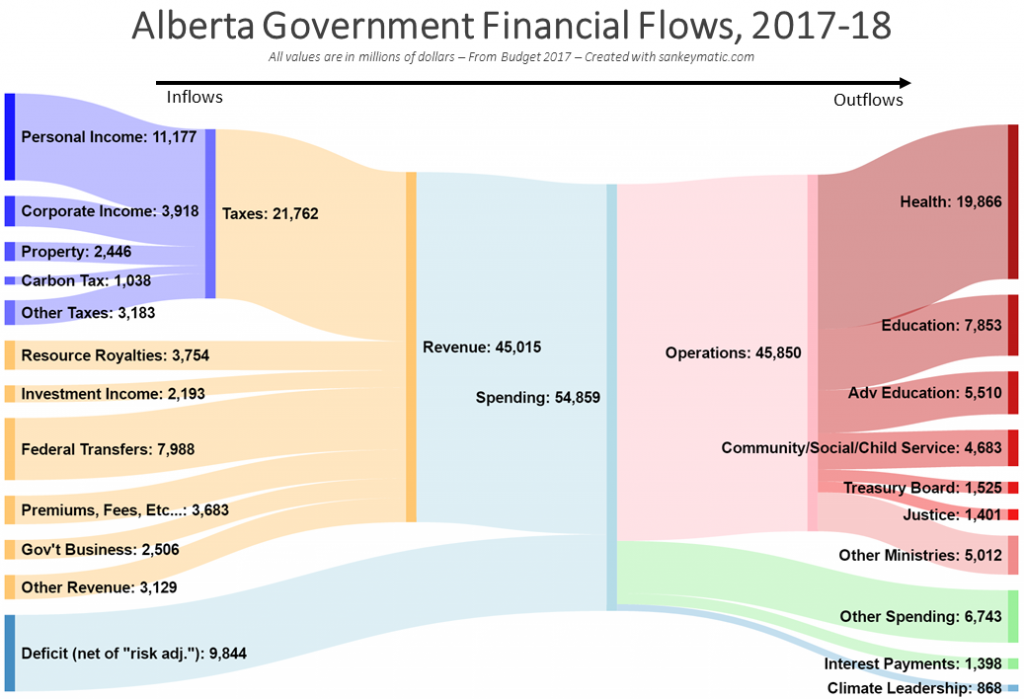

Provincial taxes (dark blue) are fairly small—less than the cost of our health system, and less than half of total government spending. High spending and low taxes were possible when resource revenues were large, but today the deficit is larger than every single ministry of government except health.

Is this sustainable?

Alberta’s fiscal outlook

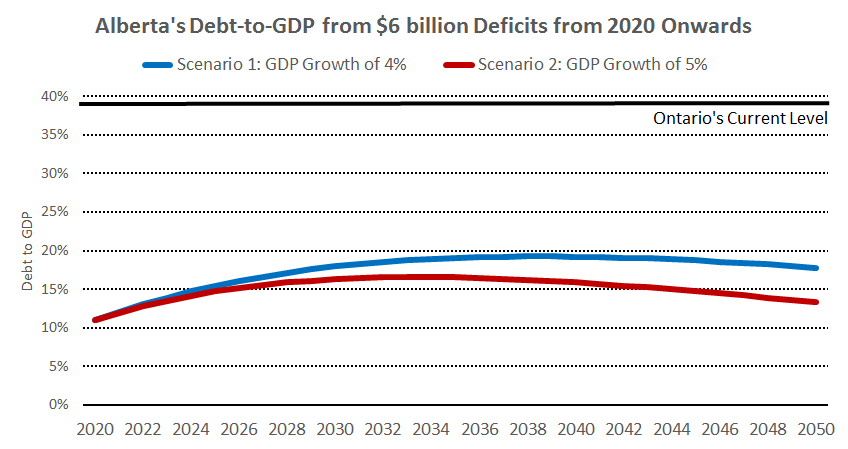

Government borrowing is not the same as household borrowing. What matters for sustainability is debt relative to the overall economy (the ultimate tax base for the government). Unlike households, economies have no clear end date, no retirement, and (typically) experience steady upward growth. And a growing economy can, in principle, sustain modest deficits indefinitely.

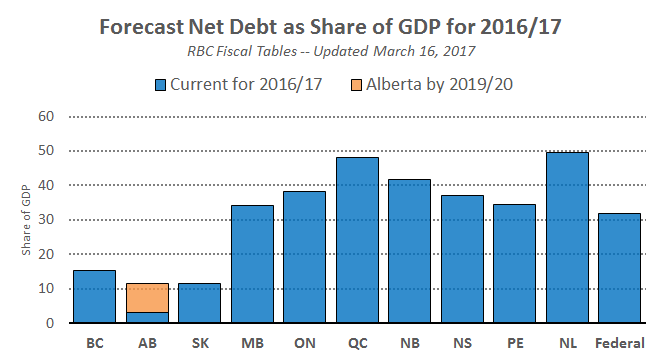

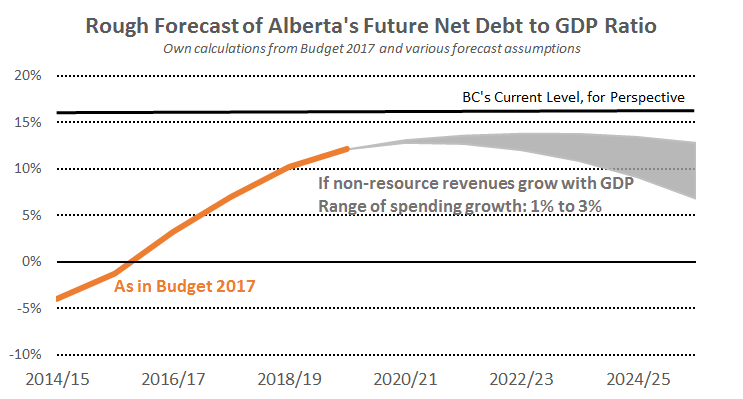

Currently, Alberta’s debt (net of our financial assets, like the Heritage Fund) is barely over 3 per cent of GDP. By 2020, it is expected to rise to 11 per cent. Though higher than Alberta has seen since the early 1940s, it is still lower than any other province.

But what happens after that? Let’s say the government runs a $6 billion deficit forever from 2020 onwards. Further suppose the province’s economy grows by 4 to 5 per cent per year (2 per cent inflation, 1 to 1.5 per cent population growth, and 0.5 to 1 per cent productivity gains). Even after a few decades of seemingly large deficits, the debt-to-GDP ratio will barely exceed half of Ontario’s current level. And remain the third lowest in the country—at worst.

A more realistic forecast, where we balance in the middle of the next decade as royalty revenues grow (which seems to be the government’s baseline projection) reveals an even lower debt ratio.

That doesn’t mean perpetual deficits are wise. Nor does it deny rising debt presents challenges if Alberta’s economy were to ever start shrinking, or that it limits our future ability to manage large unforeseen negative shocks. But these forecasts provide important perspective: there is no immediate sign of fiscal disaster in Alberta’s future. None.

More honesty is required

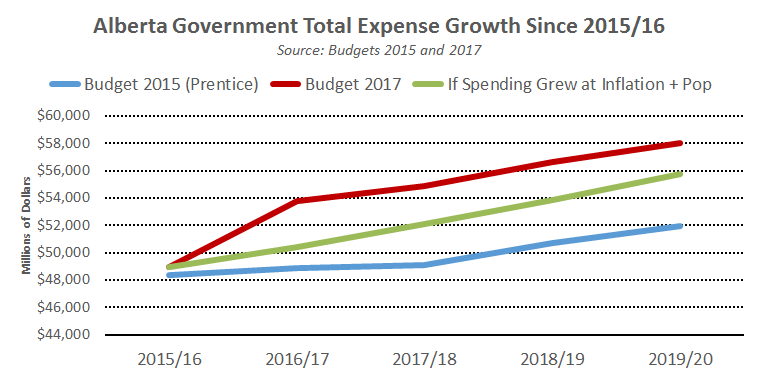

While opposition concerns around debt sustainability are misleading, the government’s claims around spending growth are equally so. During his speech to the Alberta Legislature, Finance Minister Joe Ceci claimed, “We are keeping spending growth lower than the combined rate of inflation and population growth.” He repeated the line, or some variation of it, in nearly every post-budget interview I heard.

The trouble is: it’s not true.

For the four years between 2015/16 and 2019/20, the years reported in this budget, total government spending is rising at a rate of 4.3 per cent per year on average. Excluding interest charges, total program spending is growing at 3.7 per cent. Over the same period, population growth plus inflation is 3.4 per cent. This adds up. Had spending increased with population plus inflation from 2015/16 onwards, Alberta would be spending roughly $2 billion less by 2020 and the deficit that year would be 30 per cent smaller.

So why is the Minister saying otherwise? A certain subset of operating expenses will grow at 2.9 per cent per year over the same four-year period, and this is what the government is referring to. (See page 13 of the budget.) But this excludes other important items—like Climate Leadership Plan spending, at nearly $1 billion this coming year and $1.8 billion next.

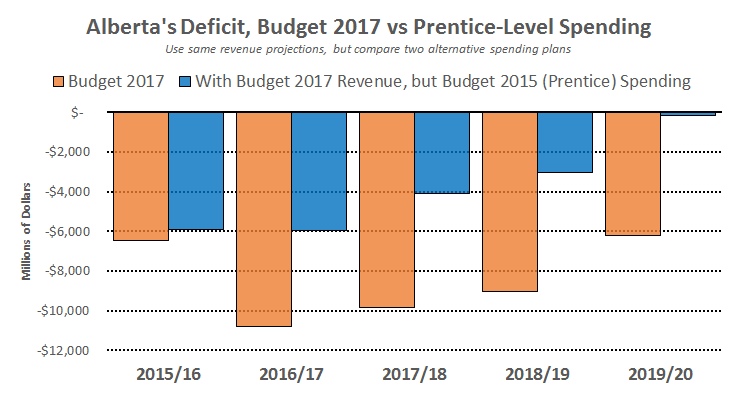

Spending growth rates matter. For example, no spending reductions are found in the Prentice government’s last budget (the blue line above), only more modest growth. Had we followed that path, even given currently depressed revenue forecasts, the province’s books would be balanced by 2019/20.

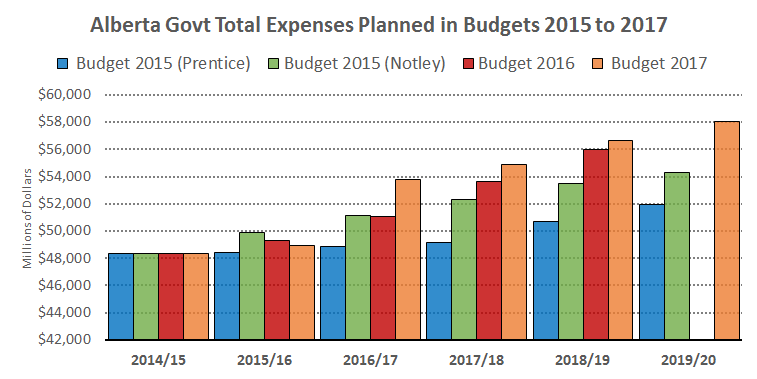

Spending is not only growing faster than the government claims, but overall levels are projected to be higher than their own past budgets planned for.

If spending remained on the path planned in the NDP’s first budget (the green bars), the deficit would be barely over $2.5 billion by 2019/20, rather than the currently projected $6.2 billion (ignoring risk adjustments).

To be sure, the additional spending may be justified. But it’s up to the government to make that case, not pretend the spending growth isn’t occurring. Given the tough fiscal choices facing Albertans, all political leaders should strive to support open and honest dialogue about how to move forward and what our priorities should be.

The royalty rollercoaster

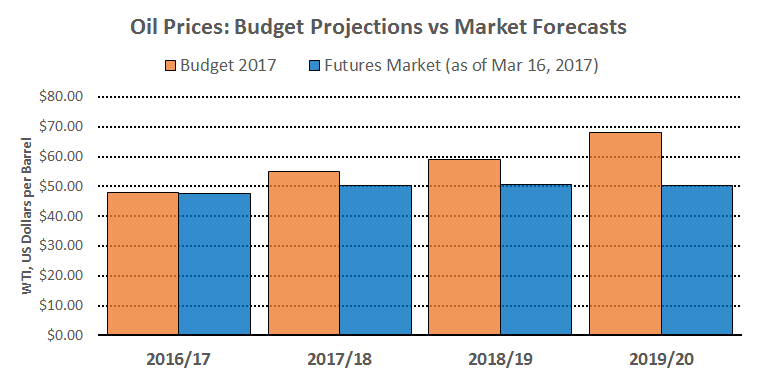

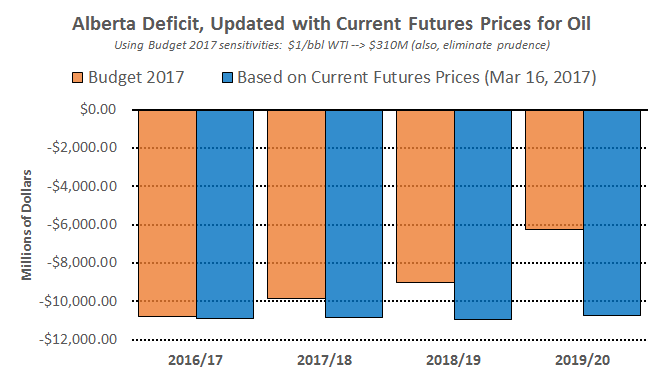

My colleague Ron Kneebone puts it best: Alberta has a substance abuse problem. We need royalties to balance the budget, and the current budget is no different. In fact, the government’s projection for gradually declining deficits is entirely driven by rising future oil prices. The government is betting prices rise to nearly $70 per barrel in a few short years, while the market currently expects prices to remain flat around the $50 mark.

The projection matters a lot. Each $1 per barrel is worth $310 million to the government’s bottom line. So if oil prices do not improve, neither will the deficit.

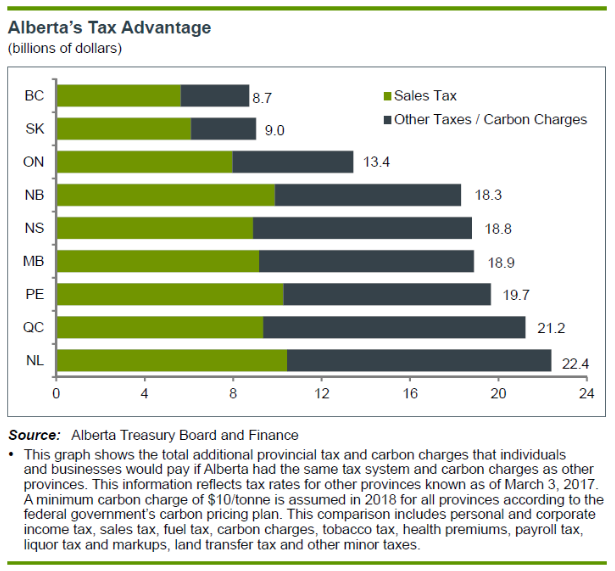

Related to this, some incorrectly view the deficit as due to a weak and undiversified economy in Alberta. Not only is the economy stronger and more diverse than people realize, the broader economy has zero to do with our budget problems. Nothing illustrates this point better than the following graph. It illustrates how much we’d raise if we adopted the tax regimes in each other province. If Alberta had the same taxes as Saskatchewan, the province would bring in $9 billion more. If it had Ontario’s taxes, the province would have a $3.1 billion surplus—despite the low oil prices.

This isn’t to say we should raise revenue—that’s a normative political question. Instead, it shows the province’s tax base is strong. The problem is not the economy, it’s our budget.

Our deficit is a choice. New revenue sources, greater spending restraint, or some combination of the two are needed to get off the royalty rollercoaster. If it’s a ride Albertans would rather stay on, so be it. But let’s make this choice with our eyes wide open to the implications. If Alberta is to make progress addressing (and understanding) our fiscal challenges, we have to start by rejecting hyperbole and by being honest about where we are and where we’re going.

Trevor Tombe is an Assistant Professor of Economics at the University of Calgary, and a Research Fellow at the School of Public Policy