Explained: How the Harper government put spending on ice

If you’re in government and want to restrain your own spending, you make it harder to move money out the door

(OTT 101)OTTAWA, JAN. 7–ICY TOWER–The Peace Tower on Parliament Hill is framed between the frozen trees in the Ottawa region following several days of freezing rain on Wednesday.(CP PHOTO/Jonathan Hayward)joh

Share

Stephen Gordon has written an excellent post about the Harper government’s quiet but rather effective efforts to institutionalize austerity. As Gordon points out, the mix of economically crazy but politically saleable GST cuts and boutique credits, transfers to provinces tied to GDP and a nominal freeze on direct program spending, have the combined effect of slowly, but noticeably, squeezing the fiscal capacity of the federal government. Cut revenues, increase transfers, cut spending, repeat.

That post, and then the morass that may be under-spending at the Department of Veterans’ Affairs got me thinking about another aspect of the strategy: Make it harder to spend money.

Spending reviews that simply impose, say, a five per cent reduction, are blunt tools and fraught. Strategic reviews that try to pinpoint under-performing, inefficient or outdated programs are risky, and not just for whatever political constituency rises to defend the program, but for the principal-agent problems that inevitably arise. How is a minister in an office with maybe 11 staffers equipped with Google supposed to out-analyze an army of departmental officials telling them that the publicly popular program is really the most inefficient and ripe for cutting? How are they supposed to know if they are trimming fat or slicing into the meat?

So, if you’re in government and want to restrain your own spending, another way to do it is to just make it harder to move money out the door. There are a lot of small but incrementally effective ways to do this. Some of us use tricks to stop ourselves from spending. For example, when my mother grew alarmed by her credit card bill, she would put her card in a block of ice in the kitchen freezer. Really. I’m not making this up.

If you’re in government, one thing you can do is to make it more burdensome for items to get through Treasury Board—a step that all programs must clear before new money can move, even if it was in the budget, even if it was ok’d by Cabinet. A comparison of the template for Treasury Board submissions in 2007 and the one in current use is pretty telling. Those submissions, drafted by departmental officials for the responsible minister, now require “risk assessments,” details on “design and outcomes,” and not one but two separate sections on costing—one to deal with funding (How much money are you asking for? Where do you think it’s coming from?) and another to validate the cost estimates (Prove to me again how you know your costing is right?). And, since January 2014, each submission has to come with a letter of attestation from the departmental Chief Financial Officer, vouching for the cost and funding estimates outlined in the submission. The Board now also suggests up to five appendices to support a submission. I’d love to know how long it now takes, on average, just to draft a submission, never mind getting the Board’s approval.

Another tactic is to end so-called “March Madness.” That’s Ottawa-speak for the tendency to try to catch-up on spending in the fourth quarter so that money allocated to the department doesn’t lapse and return to the Consolidated Revenue Fund. Why do you not want to lapse money if you’re running a department? Well, because it’s harder to get the money back once it’s gone. And, self-interestedly, executives’ own pay is partly tied to how close they come to spending in line with the official projections for the year. Yes, it’s ok to come in a little under, but not too much or you’re clearly not meeting your other performance targets.

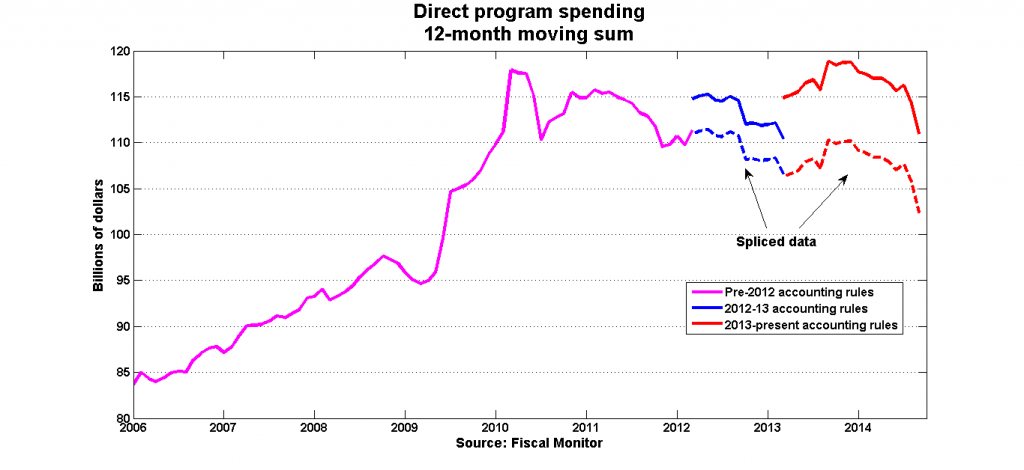

Back in February 2012, Tony Clement, President of the Treasury Board, wrote publicly to his cabinet colleagues (ok, by making the letter public we know his intended audience was not really his cabinet colleagues), warning that the Board would be clamping down on any hint of operational spending sprees near the close of the fiscal year. Gordon’s second chart (on direct program spending) seems to show the clamp down has been working.

You have to kind of squint to see it, but if you look at the slope of the line just after it goes into the new calendar year, you can see that for 2006, 2007 and 2008, there’s a bit of an up-tick in spending in the early months of the new year. Let’s skip 2009 through 2011 since those were the big stimulus spending years and the trend lines look really weird. Look at 2012 and there’s that little up-tick in new year spending again. But, following Clement’s letter, 2013 and 2014 show not only a general decline in spending, but also no more “March Madness.” So that worked!

Why would departmental executives run into a problem of having too much money towards the end of the fiscal year? Well, because it’s actually not straightforward to move money out the federal door. Parliament allocates it, based on spending projections for the year, but even after Treasury Board gives a department the authority to do something with that money, there are yet more hurdles before those dollars go anywhere.

If the money was given to hire personnel, well now you have to find and hire personnel. Not that hard you say? Clearly you’ve never hired someone under the Public Service Employment Act. There are forms, lots of them, and standardized tests to be administered, and standardized interview questions to be asked and answers to be graded, and education credentials that have to be verified (even if the candidate is already working in the federal public service) and the risk of grievances processes to manage, and… well, it’s a lot of work and it can take a long time before you have an employee receiving any salary dollars or using overhead.

The government wisely lets the Public Service Commission take care of imposing and enforcing those HR obstacles to spending. So we can’t give it too much credit there. But what about other hurdles where it can have more control?

Well, another option is to make it more administratively difficult to issue grants and contributions. Empower contracting officers to exercise more ‘oversight’ on the contracts program branches want to enter into. Change the policies, ideally with some frequency, so that people don’t get too comfortable or confident. Demand recipient organizations take on additional administrative burdens before contracts or contribution agreements can be approved. Restrict multi-year funding agreements—if the project can’t get done before the end of one fiscal year, too bad. Remind everyone of the Gomery Commission and what can happen without enough rules! The current government didn’t invent this approach but it has embraced it with gusto.

So perhaps it shouldn’t be much of a surprise that several federal departments are currently way behind on spending the money Parliament has given them for grants and contributions. A few are doing not so badly and seem to be on track to spend roughly what Parliament voted to give them. For example, Veteran’s Affairs reports[1] that at the half-way point in the current fiscal year, it has moved out $1.3 million of the $2.7 million it was allocated for grants and contributions (48 per cent) and Employment and Social Development Canada has spent $680 million of the $1.7 billion (40 per cent). I do wonder what it might be like to hand out the remaining billion in grants and contributions in just 6 months. I wonder more though about what’s happening in places like Agriculture and Transport where they’ve only moved 13 per cent and five per cent of the allocated money for grants and contributions so far. Maybe the departments aren’t spending the money because of some very good policy reason, though you’d think then they’d revise their projections.

Or maybe they are waiting for the equivalent of an ice block to thaw.

| Department | Authorities for 2014-15 ($millions) | Year-to-date (first six months) spending at September 30, 2014 ($millions) | % of authorities spent |

| Agriculture and Agri-food | $365 | $48 | 13.2% |

| Employment and Social Development | $1,702 | $680 | 40.0% |

| Environment | $107 | $29 | 27.1% |

| Fisheries and Oceans | $58 | $25 | 43.1% |

| Health | $1,683 | $1,047 | 62.2% |

| Natural Resources | $444 | $99 | 22.3% |

| Transport | $758 | $42 | 5.5% |

| Veterans’ Affairs | $2.7 | $1.3 | 48.1% |

[1] Figures in the text and table are from the most recent departmental quarterly spending estimates and are for the period ending September 30, 2014.