Even as Canada’s economy booms, prices are barely rising

Econ-o-metric: Inflation is slowly rising, but probably not enough for the Bank of Canada to hike interest rates again. The bank’s message: be patient

Share

A rare sighting in Canada today: inflation.

The Consumer Price Index rose 1.6 per cent in September from a year earlier, the most since the spring, Statistics Canada reported.

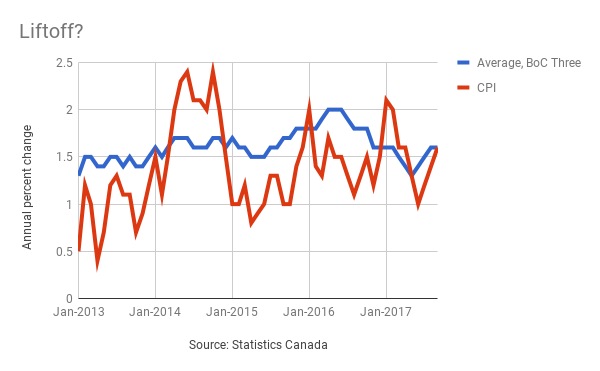

A handful of other price measures that the central bank uses to guide its policy decisions also crawled higher, but probably not enough to prompt a third consecutive interest-rate increase next week. A separate StatsCan report showed that retail sales dropped in August, adding to evidence that economic growth slowed in the third quarter.

Why the latest price data matter

CPI is like the Bank of Canada’s dartboard.

The central bank’s main job is to keep inflation advancing at an annual rate of about two per cent. That sounds easy, but it’s not. Policymakers and economists around the world are puzzled that inflation has remained weak despite years of ultra-low interest rates and recent evidence of strong economic growth. Canada’s economy has been doing extremely well for more than a year, yet inflation only now is showing signs of life.

Glass half full

Inflation is a difficult variable to assess because it means different things to different people.

Some worry that the recent strength of Canada’s economy is a mirage. If you are one of those people, you might like the latest price figures because they suggest the central bank can safely leave its benchmark interest rate unchanged at 2 per cent for a while: 1.6 per cent is still some distance from 2 per cent.

Other people worry that years of ridiculously low borrowing costs have created asset-price bubbles. If you are one of those people, you also might like the latest inflation report because it contains hints that prices are beginning to rise, which would give the central bank reason to (finally) push interest rates back to a more normal setting. The central bank must anticipate where prices are headed: if it waits until CPI touches 2 per cent, it may lose its grip on inflation.

The headline CPI is the Bank of Canada’s target, but just as a target shooter must adjust for the elements, the central bank is guided by measures of inflation that smooth the influence of volatile prices such as gasoline and food. Policymakers keep an eye on three indicators of “core” inflation. Bay Street economists tend to average the three numbers to create a proxy of how much pressure the central bank might be feeling to adjust borrowing costs. That average has been creeping higher for the past couple of months.

Glass half empty

Or you might be a normal person who cares about how much spare cash he or she has left at the end of each month. And if you are a such a person, you probably noticed that you had a little less walking-around money in September. The price of gasoline surged 14.1 per cent from a year earlier, compared with an 8.6 per cent annual increase in August. The cost of food jumped 1.4 per cent, the biggest year-over-year gain since July 2016. The cost of shelter also increased.

Those increases hurt more than they might have in the past, because wages only recently have started to increase in line with the pace of inflation.

A message from the Bank of Canada governor

One of the great debates in economics currently is why inflation is so weak. Bank of Canada Governor Stephen Poloz is unsure what all the fuss is about.

The rebound from the financial crisis was slower than anyone expected, but Poloz told a few journalists in Washington last weekend that the business cycle is working as it always has. After a downturn, there comes a stage where “demand starts creating its own supply,” as companies expand to keep up with orders and take advantage of new opportunities. The extra capacity, whether through retooled factories or a larger pool of job seekers, puts downward pressure on inflation. Poloz reckons Canada is in that phase now.

“While that’s happening, wages don’t move much, inflation doesn’t move much, it’s all good,” Poloz said. “One of the things that I’m often puzzled about is how many folks are writing about how inflation is missing in action and all of that. That’s exactly what happens at this stage of the cycle. It is pushed out further, and that’s a good thing.”

Bottom line

The main reason to watch inflation at the moment is for clues on when the Bank of Canada will next raise interest rates, a decision Poloz says will be based on a month-by-month assessment of the latest data. There is a spark in the price figures, but no flame. The central bank will announce its next interest-rate decision on Oct. 25. With inflation tame, expect policymakers to leave rates unchanged. Inflation is coming, but it’s not here yet.