Bright Idea: Fake blood that behaves like the real thing

A blood substitute that’s miles ahead of cornstarch and food colouring

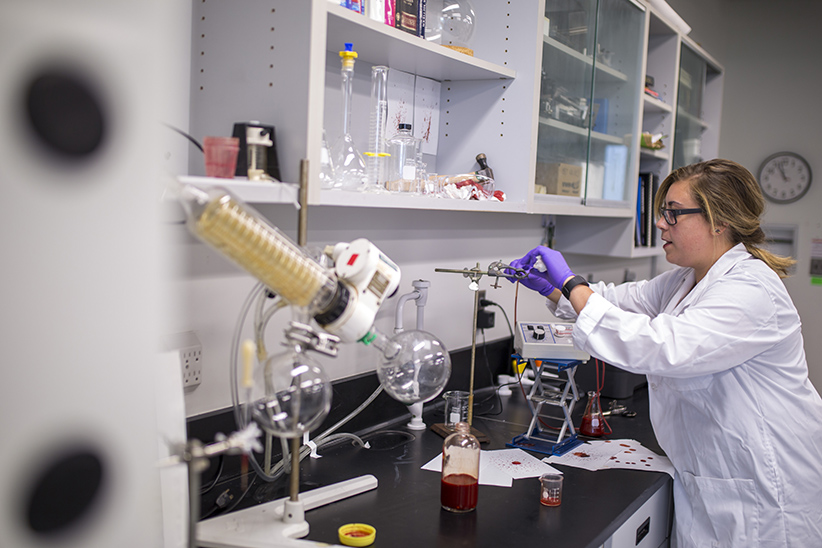

Theresa Stotesbury with the synthetic blood substitute that she created. (Photograph by Nick Iwanyshyn)

Share

Great minds do not think alike, and that’s why universities and colleges are the mother of inventions. Click here for the rest of our Bright Ideas series.

Theresa Stotesbury: Trent University

Remember Dexter, dressed in head-to-toe white, spattering blood onto the wall for analysis? Well, Dexter might not have had this problem, but for non-murderers in the field of forensics, buckets of blood aren’t easy to come by. “First of all, particularly at academic institutions, there’s a lot of time-consuming paperwork to obtain ethical approval to use human blood,” explains Theresa Stotesbury, a 27-year-old Ph.D. student at Trent University’s materials science program. Once you make it through the red tape, she says, “blood’s a really tricky fluid to store and maintain. Over time, it will clot and coagulate and not behave the way it would when it directly leaves the body in a crime-scene context.”

Then there’s the yuck factor. “There are biohazard and safety risks. And it’s also pretty gross.”

So with a background in forensics and a first-hand look at crime scenes, which highlighted a need for a synthetic alternative, Stotesbury got to work on a safe, consistent synthetic blood that will move and behave like the real deal, in classrooms and forensic labs alike.

It’s not a blood substitute, but rather a fluid that acts like blood, demonstrating properties like density, surface tension and viscosity.

With the support of Trent’s renowned forensics program and a $150,000 NSERC Vanier Canada scholarship, Stotesbury is perfecting fake blood, which she hopes will become a standardized norm across the field.

But what, exactly, is this “blood” made of? “The recipe is a trade secret,” says Stotesbury, “but it’s definitely not corn starch and water.” The biohazard-free formula is also very safe. “I wouldn’t eat it, but you can certainly get it on you and wash it out of clothes, no problem.”

The liquid’s already made its way into training programs for forensic practitioners, and potential commercialization brings more possibilities—in the entertainment industry perhaps. But Stotesbury is focusing for now on its educational use. “It’s a bit like Dexter,” she admits, “but not the serial-killer part.”

How to be a bloodstain pattern scientist

Inventor: Theresa Stotesbury

Position: Vanier Scholar, Ph.D. candidate in materials science at Trent University

Undergraduate degree: Bachelor of forensic science from Trent University, 2011

Graduate degree: Master’s of forensic science from the University of Auckland, 2012

Ph.D.: Materials science at Trent University (in progress)

Other pathways to this career: Policing, civilian forensics, graduate degrees in other applied sciences, certifications in bloodstain pattern analysis

[widgets_on_pages id=”Education”]