When students live in luxury

From 2015: Forget everything you know about spartan student housing—condos offer a new kind of university lifestyle. But is it worth it?

MACLEANS-LUXE-02.07.15-WATERLOO,ON: The LUXE residences boast spacious common areas and private bathrooms for student living in Waterloo, ON. Photograph by Cole Garside

Share

A blue sky. A residential street. At one end, a row of gleaming buildings. One is sleeker, glossier, more modern than the rest. “Looking for an investment at the head of its class?” a female voice intones, her posh British accent rising above an ambient beat. “Meet Icon, Ontario’s new investment condo development . . . for students and young professionals.”

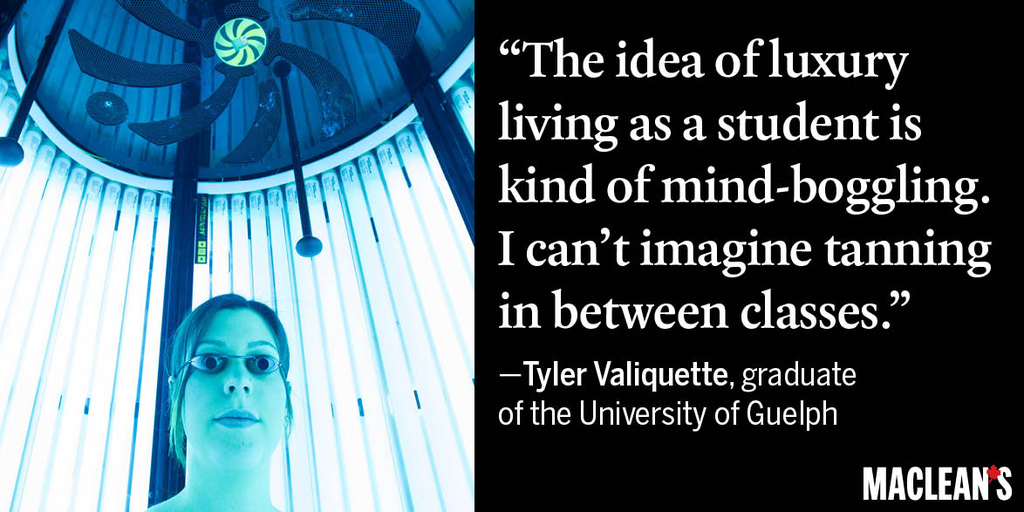

High-end high-rises like Icon, in Waterloo, Ont., are the latest student housing trend in Canada. Owned by private companies and marketed to wealthy families and investors—who buy them and turn them over to management companies to rent to students—so-called “student condos” come with yoga studios, tanning beds, movie theatres, billiards rooms and rooftop patios. Since they emerged onto the Canadian market three years ago, they have drawn wide-ranging criticism from neighbourhood groups, some universities, and even the students they want to attract.

“The idea of luxury living as a student is kind of mind-boggling. I can’t imagine tanning in between classes,” says Tyler Valiquette, a graduate of the University of Guelph. As a commissioner for the university’s Central Student Association, Valiquette investigated the impact of a proposal by Toronto-based Abode Varsity Living to build a student complex with two linked towers on 17,000 sq. m near the Guelph campus, which he says caters to the one per cent.

He calculated rents in the new buildings are likely to be $700 to $800 a month per person in order for investors to make their money back on the condo suites, double the amount he and most of his friends pay for accommodation now. That gentrification could come at a price to other students who cannot afford Abode’s development. “The emergence of these buildings with hundreds of units could really affect rent prices in Guelph, so that’s a huge concern.”

Historically, student housing has been anything but luxurious. During the Dark Ages, many students ate tripe and slept on beds made of straw. Even modern residences are something to be endured, not enjoyed.

It wasn’t until the early 21st century that private companies began tapping the student housing market. The first was a Texas-based developer called American Campus Communities, which created a Canadian Campus Communities subsidiary soon after its initial public offering in 2004. According to senior vice-president Melinda Farmer, there are two projects in Calgary, two in Waterloo (the Luxe I and Luxe II are just four blocks from the Icon development) and three more in Ontario: Oshawa, Hamilton and London.

“Part of this is driven by the increased numbers of international students,” explains Scott Mabury, the University of Toronto’s vice-president of university operations. “They’re much more likely to take up our first-year residence guarantee. So we have need for more student housing—that’s part of the reason why we want to build a new residence.” As enrolment is growing, endowments are shrinking and government funding is drying up. Universities want more students, but can’t afford to house them all.

Knightstone Capital Management, a Toronto-based real estate and development company, partnered with the University of Toronto in 2010 and drafted plans for a 759-bed tower across from the main campus downtown. Residents were outraged when they learned the neighbourhood would be overrun with hundreds of university students. The details of the arrangement, which would have lasted 99 years, were eventually posted on the university’s website, but not before the school had written a 2,600-word statement blasting the “hostile” neighbours and vowing to continue partnering with private development companies even if the Ontario Municipal Board shut them down. Which it did, because the project was “12 times the permitted density” for the location.

Meanwhile, in Vancouver, a local entrepreneur is turning a luxury hotel into housing for international students with rents between $900 and $2,500 in a city with less than one per cent vacancy rate. CBIT Education group has nine similar projects in the planning stages and wants to bring 5,000 new beds onto the market. Viva Suites, which already come with full kitchens with marble countertops, ensuite laundry and views of the nearby mountains and marina, will be renovated to provide 230 beds, while the developer plans to add airport shuttles, daily hot meal service, and access to tutors.

Glen Weppler, director of housing and residences at the University of Waterloo, is worried about how Icon’s two 25-storey student high rises with more than 800 units will change the face of the community. “I think one of the dangers in any kind of housing situation where it’s densely populated, and it attracts only one type of person—obviously we’re talking about students—is that it’s going to create a different type of environment,” he says.

As universities are being run more and more like businesses and it gets easier and easier to get in, Valiquette says they attract a different kind of customer—one with lots of money. The students who choose to live off campus from the beginning will miss out on the residence experience that enriches and augments the classroom lessons and adds to the richness of university life.

“It better connected me to campus with different student groups and organizations and clubs, and helped define who I was in university,” Valiquette says of his time in residence. “That’s a very valuable thing for young people to go through.”

Aside from their impact on cities and communities and the university experience, student condos represent a more fundamental problem. By prioritizing comfort, they are undermining the reason universities exist. For the vast majority of students, furthering their education is something they have to do in order to survive, not something they do because it comes with a tanning bed. The view that luxury is the defining aspect of student housing is rooted in the belief that money, not work, is the key ingredient to a student’s success. In this consumer model of education, getting a degree is a lifestyle that is chosen and ultimately purchased.

Until recently, the spirit of student housing remained largely intact. You took a room however it came and ate whatever they served you. You did these things knowingly, even willingly, because you understood that the struggles you encountered, the discomforts you endured, were a rite of passage.