Rescuers from Ahousaht tracked single flare to the chaos of the capsize

How a group of fisherman prevented a far worse tragedy when disaster hit Tofino’s whale watching boat, Leviathan II

The bow of the Leviathan II, a whale-watching boat owned by Jamie’s Whaling Station carrying 24 passengers and three crew members that capsized on Sunday, is seen near Vargas Island Tuesday, October 27, 2015 as it waits to be towed into Tofino, B.C., for inspection. (Photograph by Adam Chilton)

Share

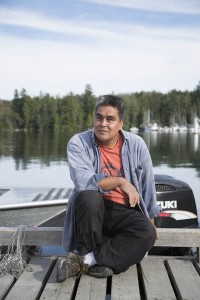

Sunday was a perfect fall day, says Clarence Smith, a fisherman from the Ahousaht First Nation, known locally as Smitty. By noon, the sun had mostly burned through the morning fog. “There was a little swell. A little chop. A light breeze,” he adds. Smith was out for halibut with his longtime fishing partner Ken Lucas. Around 3:45 p.m., Lucas was at the stern, hauling in line when he happened to catch a red flare cutting through the blue skies off Plover Reefs, west of Vargas Island. The pair ripped in the rest of the line, then headed for the white trail the flare had left behind. Conditions were changing: the wind and chop had picked up substantially. Still, the crossing took no more than 10 minutes.

“At first, we thought it was a sailboat up on the rocks with no power,” says Smith. But his stomach sank when they got closer. It wasn’t a sail, it was the bright white bow of the Leviathan II, a Tofino whale-watching boat, poking just 3.5 m above the break.

They heard screams and headed for a bright, orange life-raft. The survivors waved them off, pointing to a man clinging to the nose of the Leviathan II with what little energy he had left. “He had a line wrapped around and around his left ankle,” says Lucas. “We had to cut through it in three places.”

“You’re going to be OK,” Lucas told the man as he pulled him aboard. “You’re going to be OK.”

“I had no time to stop and think,” he remembers. “All I wanted to do was get people on the boat. My heart was pounding. My adrenalin was pounding.”

The pair then headed for two women who were clinging to each other in the water. “One lady said her leg was broken. The other lady was pregnant,” says Lucas. “Help the pregnant woman first,” the injured woman said. Once the two women were aboard, they headed back to the life raft, and brought 10 more people onto their 21-foot fishing boat. At first, “nobody said anything,” says Lucas. “They laid there lifeless. They didn’t say a word. They were exhausted.” Off in the distance, they could hear others screaming from the rocks.

That’s when Peter Frank Jr., 33, arrived on the scene and transferred some of the passengers from Smith’s overloaded boat onto his, called the White Star. As they headed for town, he could hear the terrified survivors crying and whimpering whenever they hit a wave. Some were throwing up. Frank tried to calm them, telling them his name and a bit about the vessel: “You’re OK now. The White Star has seen some ugly seas. This is a big, safe boat. Just hang on.”

Francis Campbell, an Ahousaht boat taxi driver, also arrived onsite with his wife and two passengers—hikers headed for Tofino. Campbell found one group of five survivors clinging to a kelp bed, to keep from drifting out with the tide. Then he found a group of three more survivors; they were holding an elderly woman above water. They were soaked in diesel. Heavy oil was painted across their faces and clothes. They were so slick, in fact, the rescuers had trouble pulling some passengers aboard. Campbell, who has barely slept since the accident, says he can still smell the diesel.

“I’m pretty sure they were in shock,” adds Smith, about the survivors he picked up. “We covered them up with everything we had—sweaters and jackets.” Some had lifejackets on. Many did not. One woman told them she was a member of the Leviathan II crew. She had shot the flare, the only one she could find, she told them.

By then the Ahousaht fishers had radioed for more help: “We need all the help we can get.” Within minutes, a half-dozen other boats had arrived. As they headed to shore, the Leviathan’s II’s passengers told Smith and Lucas they’d been broadsided by a “rogue wave.” “It caught them, curled them, ripped through the boat, then tipped them right over,” says Lucas.

Five people were killed, all Britons, including a father and his 18-year-old son. One man, a 27-year-old from Australia was still missing as of Tuesday night. The RCMP dive team was sent out Tuesday morning, but were originally searching the wrong location—too far southeast of Plover Reef. Two search boats in the area redirected the RCMP. A deckhand from the Leviathan II later arrived by Zodiac to assist them.

Twenty-one people were saved on Sunday, thanks to that single flare and the rescuers that followed it. Lucas says his “chest is heavy.” There’s “lots running through my mind.”

Late Monday, four members of the Transportation Safety Board arrived on-scene in Tofino. Marc-Andre Poisson, director of marine investigations, says the investigation into what went wrong could take months. Poisson said the ship has been towed to a nearby island by the Coast Guard, but remains underwater.

As Poisson finished speaking, hundreds began filling Tofino’s Community Hall for a potluck dinner to thank those involved in the search and to bring the community of 1,800 together. Among them were rival whale-watch outfitters, community leaders, and John Armstrong, the town doctor who treated the injured on Sunday afternoon.

Jamie Bray, the owner of Jamie’s Whale Watching, which operates the Leviathan II, spoke briefly at the dinner. He was “deeply traumatized” by Sunday’s events, he said through tears. “We’ll get our community back,” he said before ducking out a side entrance, to avoid media.

The next morning, several men from Ahousaht and Tla-o-qui-aht resumed their search for the missing man. “Our people are still out there searching and looking,” said Tla-o-qui-aht councillor Elmer Frank. “We don’t hesitate,” says Richard Little, a lifelong fisher who drives an Ahousaht water taxi.

The capsize site is an ugly stretch of turbulent water. Only a rocky outcrop—a resting place for dozens of sea lions—stands between Vargas Island and the open ocean. Two-metre swells hurtle into the rocky island, kicking up white spray several metres into the air. Behind it, the shallow waters and tidal pull create whirpools and freakish wave patterns and occasionally “rogue waves,” as they are known on the coast. They can come solo, or in twos, fours and eights, says Little. Local fishers all seem to have a story of surviving one.

The trick, says Little, is to ride alongside the wave, not try to veer away from or into it. Ideally, it will crash over the boat. At that point, the driver must keep moving, finding a new balance with the several tonnes of water. The Leviathan II appears to have been broadsided at the stern, according to what some survivors told rescuers. If that’s the case, says Little, pointing to a series of ugly waves being kicked off a shallow reef at the accident site, the boat didn’t stand a chance.

“The water’s pretty shallow there—eight to 10 fathoms deep—and the currents ripping the wave must have been six to eight feet high. The boat flipped over so fast nobody had time to react or grab hold of anything,” says Lucas. Sitting in calm, clear waters on Tuesday, the boat’s hull appeared in perfect condition, with no visible scars or scratches, seemingly ruling out initial reports that it might also have hit rocks before flipping.

This is the second fatal accident for a boat operated by Tofino-based Jamie’s Whaling Station. In March 1998 a passenger and the operator of Ocean Thunder died when it, too, was swamped and rolled, throwing all four people aboard into the near Plover Reefs, the same area where the Leviathan II sank. In the earlier tragedy, there was no time for a mayday message. Two passengers were rescued after two hours.

“All wore coverall PFD [personal flotation device] suits; while the passengers’ suits were properly worn, the operator’s suite was partially zipped,” a Transportation Safety Board investigation later reported. “A factor contributing to the occurrence was that the operator did not fully appreciate the conditions the boat would meet at the time of the accident in the turbulent waters in the vicinity of reefs,” the report said.

When local fishing guide Lance Desilets arrived on the scene, two boats were leaving with passengers from the Leviathan II; some were dead, some were alive, he says. “I knew the boat,” says Desilets—everyone in Tofino does. “It’s a big, comfortable white boat.” The captain, Desilet says, is “a great guy, an older gentleman with lots of years experience on the water.”

On Sunday a Coast Guard helicopter was flying above, organizing search patterns for each boat on the water. The scene was chaotic, with waves crashing and the dull, thump, thump of the chopper above. “But all I could hear was the radio chatter,” says Desilets. “We were trying to tune everything else out, to concentrate on the radio, on finding the missing. “The mood was “very sombre,” very grim.

They knew that for those in the water, every minute mattered. The water is currently 12 degrees C offshore, and a few degrees colder in the open Pacific. Survivors would have gone into “cold shock,” which causes immediate hyperventilation, triggering the gasp reflex, according to research by Gordon Giesbrecht, a University of Manitoba professor who studies the body’s response to cold water. Survivors would have been struggling to breathe regularly, which can trigger hypertension and lead to sudden death.

John Forde, who runs the Tofino Whale Centre, who was assisting with the rescue Sunday, says that a large ship like the Leviathan II wouldn’t require that passengers wear lifejackets at all times. “On our boats and all the open vessels—Zodiacs or smaller ships—everyone is in a Mustang floater suit, or a survival suit. But on the larger boats Transport Canada rules are that you have to have a certified lifejacket for every passenger. It’s like on the ferry or a cruise ship. But the certified lifejackets are those big keyholes—nobody really wants to wear them. Unfortunately, it’s the cold that gets you.”

In a simple lifejacket, the cold water makes it hard to keep your head above water. The muscles grow increasingly weak, because the blood is rushing from the extremities to the body’s core, to try to protect the heart. In the hands, where blood circulation is negligible, this leads to “finger stiffness, poor coordination of gross and fine motor activity, and loss of power,” according to Giesbrecht’s research. Even those pulled from the water Sunday afternoon were still at risk of long-term hypothermia, as their core temperature would have continued to drop long after they were removed.

In the Ocean Thunder accident, the sea water temperature was 11.5 degrees C. Studies of cooling rates for an average adult holding still in ocean water of 11.5 degrees C (wearing a standard lifejacket and light clothing) show a predicted survival time of about 1.8 hours, the safety board report estimated. “The board is concerned that, because the current regulations do not reflect the need for thermal protection, mariners and passengers on small vessels and small fishing vessels may be exposed to undue risk of hypothermia,” the report concluded.

Tofino Mayor Josie Osborne says as soon as she got word of the accident on Sunday, at 4 p.m., she activated the city’s Emergency Centre above the Fire Hall to coordinate search and rescue efforts.

There, the mood was “definitely very sombre, and a little bit tense as events unfolded,” Osborne says. “Slowly we were being given news of how many died. First two, then three, then four, then five . . . It quickly goes from bad to worse and worse. It gets to a point where you are grateful there are any survivors at all.” It was about the worst day she could ever imagine. “Nothing prepares you for it.”

Once the boats began delivering survivors to the community docks, the tiny community ran into a problem: The survivors all needed medical assistance. But the local hospital only has 10 acute care beds. “It just wasn’t possible to deal with everyone at once,” says Osborne. So “private homes were opened up” along the hospital route, she says. “So people could be warmed up and fed and just be with people—to begin recovery.” Two of the survivors were reportedly flown to a hospital outside of Tofino.

Osborne says there has been an outpouring of offers of support from businesses and locals: “So many lodges, hotels and B&Bs have stepped up and said: ‘If you need my space, it’s yours.’ ” Restaurants are meanwhile offering food. Retail stores have donated clothing and blankets. “And then the most important thing,” Osborne adds: “That human presence, just being here for everyone.”

Late Sunday, Campbell and his wife went to the hospital to see how their elderly passenger was faring. The tiny, local hospital was a zoo: “It felt like a big city hospital,” he says.

But the lone doctor on staff took time to see them. He said one survivor had told him she believed their rescuers from Ahousaht were angels sent from heaven. After being thrown from the Leviathan II and surfacing in the cold, rough Pacific waters, they realized what danger they were in: Who would ever find them? How long could they survive the icy waters? But survive they did, because within minutes the men—and one woman—began arriving from Ahousaht.

—with Ken MacQueen