Jonathan Vance: ‘I’m not satisfied at all with where we are at’

Noémi Mercier in conversation with the Chief of the Defence Staff of the Canadian Armed Forces on sexual assault and harassment in the military

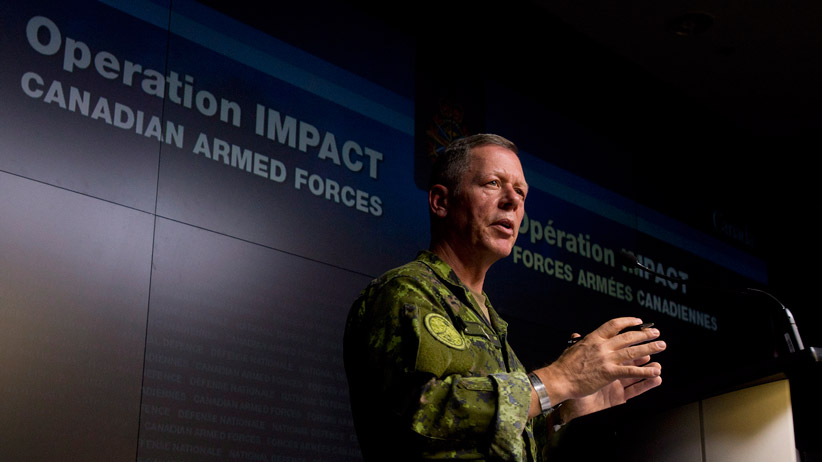

Commander of Canadian Joint Operations, Lieutenant-General Jonathan Vance, speaks during a technical briefing, Monday, January 19, 2015 (Adrian Wyld/CP)

Share

In 2014, Canada’s Chief of Defence Staff Tom Lawson ordered a review of military programs and policies in response to cover stories in L’actualité and Maclean’s.

Journalists Noémi Mercier and Alec Castonguay spent a year delving into the culture of sexual violence in the Canadian Forces. They discovered there are five sexual assaults every day in the Forces, after poring through documents obtained through the federal Access to Information Act—a notoriously slow process that often produces heavily redacted documents.

Here, Mercier talks with General Jonathan Vance, Chief of the Defence Staff of the Canadian Armed Forces. On Feb. 1, Vance released a progress report on the review.

If you had to give the Canadian Forces (CF) a score for its way of dealing with cases of sexual violence today, what would it be?

I think we started well, but we’re late to need. I’d say if you look at this from a macro perspective, from a timeliness point of view, we get a failing grade. I’ll tell you that I’m not satisfied at all with where we are at right now. There are still incidents of inappropriate behaviour occurring. There are still victims who haven’t come forward because they don’t know who to trust or who to have faith in.

We were appropriately criticized for our sexualized culture. It takes time to change a culture. I’d say we get a passing grade for our intent, for our ambition, for the initial activity. Operation Honour has generated a range of activities from additional training, to broader awareness to leadership engagement at all levels, right down through the ranks of the CF to the very lowest level. We have taken our failings, and shone a spotlight on them.

If you’re asking me the question, based on the number of incidents, how we are in terms of the sexualized culture, we haven’t moved very far yet along a spectrum of where we expect to get to. We just started. We demonstrated the will to act. Now we’ve got to follow through, and we need to be judged over the long haul.

Can you paint the picture, in concrete terms, of the sort of Canadian Forces that you want to see? What does that look like to you?

The complete elimination of harmful and inappropriate sexual behaviour is what my target is.

Is that a realistic goal?

I have to believe that it is. The CF that I want is where the members of the armed forces are reflecting back to me that they’re happy and motivated, families are well taken care of, [that] it’s a good place to come to work always, despite the fact that the ultimate liability lies an order away. I live in a world of unrealistic expectation: we’re supposed to try and do the impossible. I think we can have an armed forces where we respect each other. I’d rather be accused of trying hard and failing than not trying hard enough, honestly.

What time frame do you have in mind for achieving that goal?

It’s a never-ending horizon. We’re always going to have to get better with our people.

If we want to make this sophisticated, we want to make it last, we want to make it persistent, we want to make a genuine cultural change, we can’t just say we’ve done something and then we’re done. No no no. This is a lifestyle change. This is full-time. This is forever.

You’ve said that the CF has been insensitive and tone-deaf to sexual misconduct. How do you explain that? How did that happen?

Because we didn’t see this harm through an operational lens. We didn’t see this as a degradation in our ability to generate effective forces to do what Canada needs us to do. We train people to be really good with their weapons so that they’re confident in that weapon. We were tone-deaf to the fact [that] if you’re not confident in the people around you, if you are being victimized, you’re less likely to be a member of a team that is as productive as they could be.

Although we say “take care of the troops,” sometimes we forget to do it. I want to turn that around. Operation Honour is going to be part of a wider effort to look at how we treat people throughout the course of their career, from the time you’re interested to the time you’re buried.

I know it’s sometimes counterintuitive to hear an armed forces talk about healthy and safe work environments. Well, it’s not inconsistent at all. What we need to have is people that trust each other, that have a good foundation, ethics and a solid basis for teamwork and only then can you put them into harm’s way. Otherwise you fail. This is fundamental to the success of our institution in operations.

How do you convince the very leaders who were turning a blind eye to this issue last year that this is a serious problem and that it should become a priority? Do they magically take the problem seriously just because you say so?

There is no magic. We have to earn this every day. There are people in the armed forces who don’t think this is a problem. That’s true. But the fact that the chief of the defence staff and the senior leadership have recognized the problem, that we’ve got external stakeholders involved in this, that we are holding ourselves to account, all of this, over time, will convince people.

As we put training and education in place, so that when people first touch the armed forces and are in recruit training, we say, “This is how you are to function, how you are to behave,” over time those new people grow up to be the senior people and over time culture changes.

And it’s going to take an awful lot of intensity of effort for a very long time for the changes to occur.

Have you observed changes in behaviour since you launched Operation Honour?

I have seen the level of interest and focus on this issue increase. Operation Honour is a known term. There’s nowhere I go that I don’t speak about it.

Have I seen behaviour change in terms of the reduction of harmful and inappropriate sexual behaviour? It’s too early to tell. We have to build up some baseline understanding of where we are. We’re going to develop more sophisticated survey methods with the help of Statistics Canada. I get full knowledge instantly if there is a sexual assault that is reported to the military police. I get that right away and I see where we start the investigation and take the mitigating measures.

I do know that senior leadership behaviour has changed. In the case of HMCS Athabaskan*, a complaint was made and instantly the chain of command and the leadership reacted, with Admiral [John] Newton immediately involved. The victim got support instantly, the perpetrator was removed, and it was dealt with well. That is going to become a vignette of how to do things right, we hope.

I’m still in contact with men and women who were victims of sexual assault and sexual harassment in the Canadian Forces. The common thread is they feel this incredible frustration about the lack of sensitivity that they experience at every level of the organization. Whether it’s in dealing with the military police or trying to get medical help or counselling, you name it. It’s more than a few bad apples that just didn’t get the message. The indifference is institutional.

It’s true. We are a bureaucracy that sometimes has difficulty dealing with the challenges of an individual, that kind of dealt with cookie cutters: we tell you what to do, your career is not customized in any way shape or form. We don’t want to be that armed forces anymore.

The only thing I can tell them is if they’re still suffering in any way or they need to reach out, contact the centre [Sexual Misconduct Response Center, SMRC]. The centre is, in my opinion, doing well and getting better.

Some of the most damning pages of the Deschamps report are about the complaint mechanisms, whether it’s the harassment complaint mechanism or sexual assault complaints involving the military police. Damning criticism about sanctions that are incoherent and not severe enough, about the military police’s incompetence, about procedures that are too long and confusing, about cases of “minor” sexual assault being brushed off, victims not being taken seriously, etc. People who call the centre will be referred to the existing complaint mechanisms that were very severely criticized in the Deschamps report. I see very little about how those complaint mechanisms are improving. What I see is again an overemphasis on telling victims to please find the confidence to report and then everything is going to be fine. How do you respond to that?

I largely agree with you that we can be accused of having complaint mechanisms that sometimes don’t work. I admit we need to do better. And we’re trying. We’re reviewing the policies all the way through. In June of this year we’ll have the policy work done that’ll make this cleaner, in clear, concise and easy language.

So Madame Deschamps was right. People that had something to genuinely complain about could find themselves getting brushed off.

We’re addressing those things to the best of the ability that our capacity offers. The military police has altered the training programme in the academy to make sure that people understand the issue. They’re also going to make certain that there is a unit inside their National Investigative Service, which [have expertise] dealing with this issue. There are concrete steps we’re taking to make certain that if it’s related to Operation Honour, that—no kidding—it’s going to get attention.

My challenge is to make certain they report. Report!

And you’re confident that if they do, the very mechanisms that were so severely criticized in the Deschamps report a year ago, will be able to deal with it in a fair way?

Yes. If you call the centre, I am confident that you’ll get the attention you need. If you have just been assaulted, and you want a formal investigation to occur, or you want some sort of process to start that ameliorates the situation, you can call the centre. I’d also like to think that you can go to your chain of command, to your leadership, to get help. But I appreciate that it might not be uniformly applied across the armed forces. If you tried and you got brushed off, I’d love to know that. Because the chain of command has been charged by me, down to the lowest level, to treat this seriously. It’s official.

If it’s related to Operation Honour, if they say those words, and they go to their chain of command and the chain of command rebuffs them, I want to know.

And you’ll take action.

In a heartbeat.

A heavy burden falls on the shoulders of this new Sexual Misconduct Response Centre. Yet the structure that you have created is really a far cry from the centralized authority that Mme Deschamps was suggesting…

I don’t think it’s that far a cry. It’s the start point.

It’s a help line…

It’s more than a help line. You can be referred, the military police can be engaged.

Well, it’s a referral line. You can call there to be referred to what already exists but it has no new powers and very few resources.

There are also counsellors, people that can give you information, that will support you and make certain if you’re in crisis that support mechanisms are put in place, so it’s more than that.

But I admit it’s early days. I accelerated the stand-up of the centre, because we did need the help line, we did need a place for people to talk to and be referred, so I wouldn’t pooh-pooh it just because it provides that. It’s more than there was before, so it’s a start.

We’re not at full operational capability. We’re still designing it, we’re still trying to figure out where it is that we want to go. It started last September. That’s not a long time in the life of something that’s going to become a part of the institution forever.

Some critics have been arguing that the military justice system isn’t the right place to prosecute sexual offences, or even crimes in general. Some legal experts, both inside and outside the Canadian Forces, have criticized its lack of independence and impartiality. They point to other countries that have civilianized their system or done away entirely with military courts in peacetime for criminal matters. And there are critics who believe that as long as sexual assault is adjudicated within the military, justice will not be done or be seen to be done, and victims will continue to stay silent. How do you respond to that?

It’s important that while we have a justice system and I expect we will have a military justice system for a long time to come, that people in the military have confidence in it.

It is worthy of confidence in your opinion?

I believe it is, yes. So just because we do it internally doesn’t mean that it’s automatically bad. This idea that we cannot police ourselves, that because we’re military, we’re somehow in and of ourselves incapable of managing this, I reject that categorically. The purpose of the military justice system is not in question. The issue is its delivery.

I agree that the military justice system needs to evolve, we need to ensure that people are adequately trained. We want to make certain that we have excellent policing. We want to make certain that we have improvements in the way we manage sexual crime. From the treatment of the individual, to the investigation, to the gathering of evidence, and the ability to prosecute effectively. The judge-advocate general of the Canadian Forces is thoroughly engaged, I assure you. We’re talking about an institution-wide effort.

And so I’m with you. The military justice system and the application of it, there are many cases where it appeared and perhaps did wrong. But it doesn’t mean that it’s inherently wrong.

Why is it important for the military justice system to deal with sexual crimes committed on Canadian soil, not just in operations? Why not direct those cases to the civilian system? Are you open to that?

Yes, I am! So if an individual calls 911 and gets the city police to show up and it goes in a civilian court, I’ve got no issues with that whatsoever.

Marie Deschamps suggested in her report allowing the victim greater say as to whether her complaint should be prosecuted in a civilian or a military court.

I’m with her on this. This is one of the recommendations from the report that we’re working on very hard. This is not a simple thing.

So if the minister of national defence or Parliament decided to go ahead and push for some types of reforms, either to civilianize parts of the military justice system or strip it of some of its jurisdiction, how would you react?

Well if the minister of defence or Parliament decides something, I’m there!

Obviously.

The military justice system as it sits in Canada is not immune to change. So if there is a concern and we need to change either the National Defence Act or some part of the military justice system to make it better, I want that. But the bias that is out there that if you’re in uniform you’re automatically going to side with the chain of command, and somehow all the victims are not going to be treated well, I’m telling you that’s not the case. Because I am the chain of command and I will side with the victims.

You took a firm stance on the issue of sexual violence as soon as you took office as chief of the defence staff, in July 2015, in stark contrast to the more ambivalent response of your predecessor. Was there an eye-opening experience that motivated you to take that stance?

I’ve always tried to treat my people well. And so as I was in that interregnum between my former job and this job, I did my own personal research, talked to all sorts of people, from different backgrounds with different experiences in the armed forces. Then I did my own thinking on this. This is as harmful as people taking incoming fire. If a bullet hits you, we have a whole system that jumps into place; if you’re hurt at work because of harmful and inappropriate sexual behaviour, we don’t. And they must become just as important to us as someone who just took a hit or got hurt on the sports field or in training. The worst thing about it is someone did it to them, probably deliberately. So that’s a poison within our own ranks.

So you did some soul-searching, some reflection?

Of course I did.

And I’ve said it: bullies and predators, we don’t want you.

I also have witnessed those people who are bullies and predators, when it really gets hard in operations, they don’t do very well. I’ve come to that conclusion many years ago. Values count when you’re in combat. You’ve got to be in touch with yourself. Those people fall apart because the basis upon which they work is not teamwork.

Some people in the bullies and predators category hide behind the warrior ethos as their raison d’être for acting. It’s absolute bulls–t. The warrior ethos is actually one of care and concern, respect for the law of armed conflict, even the care and concern for your enemy once they capitulate. But most important, it’s the teamwork. Warriors respect each other, take care of each other.

So all of that affected me. I used that podium to take a stand on the day that I took office. Because I wanted to galvanize people into action. It was an important moment for me and for us. Something’s got to help us turn the corner, right? And I’m the leader.

CORRECTION, 16 Feb. 2016: A previous version of this story misnamed HMCS Athabaskan.