Lawyer urges greater transparency in RCMP harassment case

Charlie Gillis on the latest surprising development in a high-profile civil trial

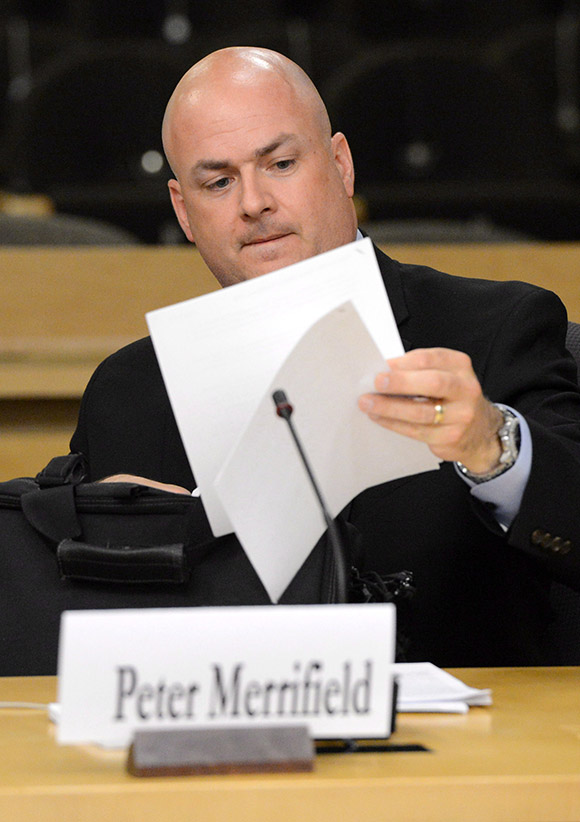

Peter Merrifield, president of the Mounted Police Association of Ontario, appears at Senate national security committee to discuss harassment in the RCMP on Monday, May 27, 2013. (Sean Kilpatrick/CP)

Share

The extreme secrecy surrounding evidence in an RCMP harassment case—including, potentially, information about the prime minister’s family—flies in the face of Canada’s open-court principle, a lawyer for major media organizations argued Friday.

“I’m urging the court to find a way to make the information available to the greatest extent possible,” Brian MacLeod Rogers told Ontario Superior Court, while acknowledging that a sealing order issued last December was intended to protect the identity of a confidential informant.

“We recognize that. We don’t want to expose a confidential informant,” Rogers told reporters outside the courtroom in Newmarket, Ont., where he is representing Maclean’s, the CBC, Postmedia and the Toronto Star. “But we want to know everything else that doesn’t disclose that person’s identity.”

The information in question arises from the case of Sgt. Peter Merrifield, an RCMP officer who is suing the force alleging workplace harassment, abuse of authority and cover-ups by his superiors. His civil trial has taken some unexpected turns (Commissioner Bob Paulson himself was forced to testify), but is drawing added attention this week as the federal government takes extreme measures to keep some of the evidence under wraps.

On Wednesday, lawyers for the Attorney General served notice they would be invoking Sec. 37 of the Canada Evidence Act—a measure Ottawa has used in terrorism cases to prevent the disclosure of information that could compromise public safety or security.

Its relevance to the contested evidence in this case is unclear.

The information is contained in affidavits submitted by one of Merrifield’s former confidential sources, who was scheduled to appear as a witness until lawyers representing the RCMP challenged the admissibility.

Lawyers for the Department of Justice tried to assert privilege that allows them to exclude confidential informants from testifying. But Merrifield’s lawyers said this case was different: the potential witness is not the government’s witness, they argued, and can safely testify so long as the identity is not disclosed.

It was during these arguments that Justice Mary Vallee issued her sweeping order, clearing the courtroom of everyone but the parties, and sealing the affidavits of “Witness X” while considering whether to allow Witness X to testify. So broad was her directive that the wording of the order itself remained under wraps, leaving members of the media uncertain as to what they could report.

“This is an extraordinary situation,” said Rogers, who cited Supreme Court precedents which required lower courts to disclose information provided by confidential informants that would not result in them being identified. “The substance of the witness’s evidence on the matters at issue would not be protected,” he said. “It has nothing to do with their identity.”

Sources have confirmed the contents of the affidavits are wide-ranging, touching on everything from the RCMP’s handling of its investigative sources to information about the Harper family’s private life—information that appears to have originated from within the prime minister’s protective RCMP detail.

Barney Brucker, who represented the Attorney General in court on Friday, argued Vallee has already considered the issues at stake. But if she decides to disclose some of the information, he added, the government will want to weigh in about what gets released.

Asked after the session whether concerns about the prime minister’s family privacy influenced the government’s position, Brucker was brief: “I wouldn’t think so. We’re protecting the public interest, and the decision is under seal and I can’t really say anything further.”

Justice Vallee has reserved her decision.